Should You Trust the Next Jobs Report?

And why are the numbers always revised so much?

Every week, I try to set aside some time to answer the burning questions that all of you send in. But sometimes, enough readers send in the same question that it’s clear a whole piece should be dedicated just to that.

In this week’s column for paid subscribers, I want to tackle a frequent question I’ve been getting the last few days: After President Trump fired the head of the Bureau of Labor Statistics, can we still trust the jobs data coming from the federal government?

And I’m going to answer it with help from Erica Groshen, who served as head of the Bureau of Labor Statistics from 2013 to 2017, during President Obama’s second term. I spoke with Groshen for an hour yesterday, asking her every question I thought you all might want the answers to. I’m going to share what I learned in three parts:

The background of the BLS and why it’s a neutral agency to begin with

How the monthly jobs report is actually put together (and what it means when it’s revised)

Groshen’s perspective on whether you should trust the jobs numbers going forward

Let’s dive in!

I. The BLS was forged in controversy

In our day — up until last week, that is — the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) has generally been considered an uncontroversial arm of the U.S. government. The data it produces can have enormous political and economic consequences, but when compared to entities like ICE or the Department of Education, it isn’t like the agency itself has often been the subject of much political debate.

That was not the case when it was founded in the 1880s.

At the time, the U.S. was roiled by fierce labor disputes: between 1880 and 1886, America saw an almost 900% increase in strikes; by the end of the decade, the country was experiencing around 1,000 a year.

The tensions were exacerbated by the fact that no one really had a clear view of the numbers on the ground. “Workers were angry because they believed that they were being exploited by robber barons who were capturing all of the benefits of economic growth,” Rutgers University economist Hugh Rockoff has written, “while employers were just as sure that the second industrial revolution had brought workers an unparalleled increase in real wages.”

This was the vacuum the BLS was created to fill. Organized labor had been hoping for a full government agency that would represent their interests (more akin to today’s Department of Labor); employers obviously pushed back against that. “The compromise,” according to Rockoff, “was an agency that would simply collect and distribute statistics about labor.” Before taking a side in the fights between labor and capital, lawmakers needed a neutral arbiter that could tell them the truth of what was going on.

The agency was originally called the “Bureau of Labor,” but its remit was that of the BLS’, not the modern Labor Department’s: to “collect information about the subject of labor,” as the relevant act of Congress put it. In that way, the BLS can be said to predate the department it now reports to. It wasn’t until 1913 that a Cabinet-level Department of Labor was created, with a mission broader than just fact-finding, and the renamed Bureau of Labor Statistics was placed under it.

“The BLS was founded to help promote industrial peace in the 1880s because employers and nascent unions were killing each other in the streets,” Erica Groshen, who led the BLS from 2013 to 2017, told me in a recent interview. “And the policy makers said, we’ll be one step closer to industrial peace if they’re working from a common set of facts about the state of the economy and working conditions and the cost of living.”

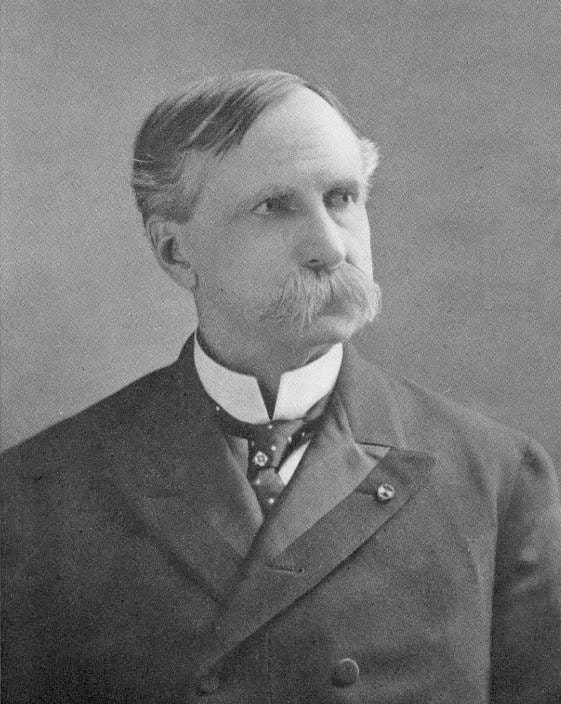

From the very beginning, it was seen as critical that the BLS would transcend partisanship. When the agency’s first commissioner, Carroll Wright, took office in January 1885, it was in the final months of Republican President Chester Arthur’s term. (Inauguration Day was in March back then.) Before taking the position, Wright checked with Democratic President-elect Grover Cleveland to ensure that he could keep the job during the transition, seeking to “safeguard the Bureau from partisan politics” and establish a tradition of impartiality.

Wright would go on to lead the BLS for 20 years, under presidents of both parties.

“Whenever the head of the Bureau of Labor attempts to turn its efforts in the direction of sustaining or of defeating any public measure, its usefulness will be past and its days will be few,” Wright wrote in his final days on the job.

“It is only by the fearless publication of the facts, without regard to the influence those facts may have upon any party’s position or any partisan’s views, that it can justify its continued existence, and its future usefulness will depend upon the nonpartisan character of its personnel.”

Subsequent administrations took those words to heart. BLS commissioners now have a four-year term, which means they regularly continue serving after the president who appointed them (since they are usually not appointed right at the start of a new administration). A commissioner appointed by Bill Clinton ended up serving for 10 months under George W. Bush. Bush’s last commissioner served for three years under Barack Obama. A commissioner tapped by Trump served for two years under Joe Biden.

That streak of non-partisanship ended a week ago today, when Trump fired BLS Commissioner Erika McEntarfer, hours after a weak jobs report was released.

“I was just informed that our Country’s ‘Jobs Numbers’ are being produced by a Biden Appointee,” Trump wrote on Truth Social, by way of announcing McEntarfer’s termination. The president took aim at the fact that, when the July jobs numbers were released last week, the numbers for May and June were both revised down (by 125,000 and 133,000 jobs, respectively). Suddenly, the Trump economy didn’t look quite as strong as we thought. The president claimed that the revisions were proof of political bias on the part of McEntarfer, although he produced no evidence to support those allegations.

II. How the jobs report is put together

I wanted to understand what goes into producing the jobs numbers that we see reported every month, in order to see if it was possible that political bias enters into the process — and to understand why it is that they’re revised so frequently. So I asked Groshen, who held McEntarfer’s job for four years, to walk us through it.