Could the 14th Amendment boot Trump from the ballot?

Breaking down the text, history, and legal questions surrounding Section 3 of the Fourteenth Amendment.

Good morning! It’s Wednesday, September 6, 2023. The 2024 elections are 426 days away. If this newsletter was forwarded to you, subscribe here. If you want to contribute to support my work, donate here.

The Fourteenth Amendment is a powerful piece of law. Its first section — which guarantees equal protection and due process under the law to all Americans — is at the heart of countless Supreme Court landmarks, from Brown v. Board and Bush v. Gore to Roe v. Wade and Obergefell v. Hodges.

Its other provisions, though, only seem to crop up as a matter of last resort. Section 4 of the amendment — which affirms the validity of the national debt — is reliably brought up during fights over the debt ceiling, suggested as a tool for the president to unilaterally dispense with the debt limit.

And then there’s Section 3, which emerged this summer as the left’s latest viral legal theory — and there have been many floated over the years — to try and oust Donald Trump from the political scene.

Ever since the January 6th attack, some academics have been whispering about the possibility of using the provision to block a second Trump term — but the idea has only begun to break into public view in recent weeks. A sprinkling of liberal and conservative legal scholars have endorsed the idea; Republican presidential candidate Asa Hutchinson even brought it up at the first GOP debate. (Many WUTP subscribers have been asking me about the theory as well.)

So let’s dig into the Fourteenth Amendment’s Section 3: its history, arguments for and against using it against Trump, and how that would even work. As always, I think it’s best to just start with what it says:

No person shall be a Senator or Representative in Congress, or elector of President and Vice President, or hold any office, civil or military, under the United States, or under any State, who, having previously taken an oath, as a member of Congress, or as an officer of the United States, or as a member of any State legislature, or as an executive or judicial officer of any State, to support the Constitution of the United States, shall have engaged in insurrection or rebellion against the same, or given aid or comfort to the enemies thereof. But Congress may, by a vote of two-thirds of each House, remove such disability.

In plain English: no one “shall” hold any federal office in the U.S. if they previously took an oath to uphold the Constitution (as a member of Congress, state official, or “officer of the United States”) and then went on to engage in “insurrection or rebellion” against the country or aided U.S. enemies. Also, Congress can override this disqualification with a two-thirds vote in both chambers.

The Fourteenth Amendment, remember, was adopted in 1868, one of the three “Reconstruction Amendments” ratified right after the Civil War. The driving fear behind Section 3 was that former members of Congress who had supported the Confederacy during the war would turn around and retake their former spots in government now that the Southern states had rejoined the Union.

That included people like Confederate president Jefferson Davis, a former Mississippi senator, and his vice president Alexander Stephens, a former Georgia congressman.

Section 3 was used only a handful of times during Reconstruction, before lying largely dormant — or, more accurately, being put to sleep — for most of the next century and a half. In 1872, Congress (with the needed two-thirds majority) passed the Amnesty Act, which removed Section 3 disqualification for “all persons whomsoever,” except former Confederates who had served in Congress between 1859 and 1863 or in a handful of other specified positions. Later, an 1898 law wiped away the disqualification even more broadly, stating:

The disability imposed by Section 3 of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the United States heretofore incurred is hereby removed.

By the 1970s, even the most senior Confederates had their disqualifications (posthumously) waived, with laws affirming that the “legal disabilities” put in place by Section 3 were removed for Davis and Robert E. Lee.

Between Reconstruction and January 6th, there is only one recorded instance of an attempt to invoke Section 3: after Milwaukee voters elected socialist Victor Berger to the U.S. House in 1918. The House blocked Berger — who was fresh off of an Espionage Act conviction — from being seated right away, impaneling a special committee to decide whether his conviction disqualified him.

The committee deliberated for five months, before eventually reporting its finding that having given “aid and comfort” to American enemies, Berger was “absolutely ineligible” for House membership under Section 3 of the Fourteenth Amendment. The House adopted the panel’s recommendation by a 311-1 vote. (Berger’s conviction was later overturned by the Supreme Court, clearing the way for him to be seated in Congress after being elected again in 1922.)

Could Section 3 be brought back to life for Donald Trump? Now that we know the provision’s text and history, I want to walk through the various legal questions that such an effort would face — as well as the competing schools of thought on each one.

1. Wasn’t the Section 3 disability basically removed by a two-thirds vote in 1872?

Yes, but a federal appeals court ruled last year that the Amnesty Act of 1872 was not intended to apply to insurrections that took place after its passage.

After January 6th, there was a string of efforts to disqualify a number of Republican lawmakers — not just Trump — from the ballot under Section 3. A case against then-Rep. Madison Cawthorn (R-NC) went so far as to reach the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals, which ruled that the Amnesty Act’s removal of “all political disabilities imposed” by the Fourteenth Amendment was purely “backward-looking,” referring to “things that [had] already happened, not those yet to come.” Indeed, Section 3 has been invoked twice since the Amnesty Act was passed: for Berger in 1918, and in 2022 for a New Mexico county commissioner who entered the Capitol on January 6th.

However, the backward-looking nature of the Amnesty Act is not a unanimous legal view. In the Cawthorn case, a district court judge (before being reversed by the appeals court) ruled that a “plain reading” of the 1872 statute’s removal of the disability from all “all persons whomsoever” would include “current members of Congress like the Plaintiff.”

Ultimately, Cawthorn lost to a primary challenger, making the case moot. The Supreme Court has yet to rule on the matter, so it is unknown if the justices would side with the district court’s reading of the Amnesty Act or the appellate court’s.

2. Did January 6th count as an “insurrection or rebellion”?

In a new University of Pennsylvania Law Review article, conservative scholars William Baude and Michael Stokes Paulsen argue that it does.

While acknowledging that January 6th “did not remotely rival” the Civil War in magnitude, Baude and Paulsen argue that the Capitol riot “arguably exceeded” other historical uprisings like the 1794 Whiskey Rebellion. The attack was “in part coordinated, not merely a riot,” they argue, and “the group’s goal...was to disrupt the constitutional transfer of power,” elevating it to the level of an “insurrection.”

Stanford law professor Michael McConnell disagrees, writing that “Section 3 should not be defined down to include mere riots or civil disturbances, which are common in United States history.” McConnell argues that a “larger scale” of violence is needed to qualify as an insurrection, not just the one-off violence of a riot.

3. Even if January 6th was an insurrection, did Trump “engage” in it?

Whether or not January 6th should be considered an insurrection has largely yet to be litigated — no January 6th rioters have been charged under the Insurrection Act — but let’s say for a moment that it does qualify as one. That still leaves the question of whether Trump himself “engaged” in it.

Again, Baude and Paulsen say “yes.” They argue that “it is questionably fair to say that Trump ‘engaged in’ the January 6th insurrection through both his actions and his inaction,” citing his tweets urging supporters to come to Washington on January 6th, his speech that day calling for them to march to the Capitol, and his refusal for most of the day to call the riot to an end.

National Review’s Dan McLaughlin, however, argues that even if one considers Trump to have “incited” the January 6th attack, the drafters of the Fourteenth Amendment very purposely created a higher bar for disqualification than mere incitement. McLaughlin writes: “A natural reading of the language suggests [the Fourteenth Amendment is referring to] someone who actually engaged in rebellion, not simply someone who incited it, egged it on, or helped create the conditions in which it arose (i.e., a participant in the riot, not simply someone who gave a speech before it started).”

4. Does the president count as an “officer of the United States”?

This is a somewhat tedious legal question, but if you return to the text of Section 3, you’ll see it’s one that will have to be hashed out. Remember, the section only disqualifies insurrectionists who previously took an oath of office as a member of Congress, a state official, or an “officer of the United States.”

Obviously, Trump was not a member of Congress or a state official. As president, was he an “officer of the United States”? It’s not as obvious as you might think.

In a 2021 paper, law professors Josh Blackman and Seth Barrett Tillman argue that an “officer of the United States” is someone appointed by the president, not the president themselves. They point to previous Justice Department opinions and Supreme Court rulings, which refer to “officers of the United States” as individuals nominated by the president and confirmed by the Senate.

As recently as 2010, in an opinion by Chief Justice John Roberts, the Supreme Court ruled that “officers of the United Staes” are appointed, not elected. “The people do not vote for the ‘Officers of the United States,’” Roberts wrote.

Baude and Paulsen contend that this argument “splits linguistic hairs,” pointing to the several times the Constitution refers to the “office” of the presidency. (“If the Presidency is not an office, nothing is,” they write.) However, Blackman and Tillman argue that there is a constitutional distinction between “office” and “officer,” with the latter not applying to the president as an individual even if the former applies to the president as an institution.

5. How would Section 3 be enforced?

This is perhaps the most imminent legal question. Before a court can answer Questions 1-4, someone will have to try to remove Trump from the ballot under Section 3. Who should that “someone” be?

According to Baude and Paulsen, the section is “self-executing.” No special act of Congress is needed, they say; all that has to happen is a state election official has to implement the provision by blocking Trump from the ballot. In this way, they argue, it is no different from the rest of the Constitution, which government officials are supposed to implement without any special instructions from lawmakers.

This view is contradicted, though, by an 1869 legal opinion from a matter known as Griffin’s Case. In the case, a Virginia man named Caesar Griffin was convicted of shooting with the intent to kill; he challenged the conviction by arguing that the judge, Hugh Sheffey, was ipso facto disqualified from serving in his role due to his service in Virgnia’s Confederate-era state legislature.

Then-Chief Justice Salmon Chase (ruling in his capacity as a circuit court judge, not as a Supreme Court justice) ruled against Griffin, deciding that an act of Congress is needed to enforce Section 3. To be clear, Baude and Paulsen dispute Chase’s legal analysis (they call it “a case study in how not to go about the enterprise of faithful constitutional interpretation”), but it has still been the general precedent for the past 150+ years in Section 3 enforcement.

This all leaves us in something of a waiting game. Considering the low likelihood that Congress would act to disqualify Trump, activists in several states have already petitioned their secretaries of state to unilaterally bump Trump from the ballot. In New Hampshire, the first-in-the-nation primary state, the movement even has a prominent Republican backer and the secretary of state has agreed to give the matter consideration.

So now, we wait and see whether any secretaries of state will try and move forward, thus sparking a legal challenge that would allow the courts — and eventually the Supreme Court — to decide the above questions.

But there is a deeper question that also needs to be asked: is that a healthy place for a democracy to be in?

Baude and Paulsen, as you might have guessed, think it is, that the health of the democracy depends on a secretary of state fulfilling their “duty” to invoke Section Three and avoid the possibility that — in their view — an “insurrectionist” will enter the White House.

Stanford’s McConnell, though, describes such a scenario as “profoundly anti-democratic,” as it would “[deprive] voters of the ability to elect candidates of their choice.” The Wall Street Journal editorial board wrote similarly, predicting that a Democratic state official unilaterally booting the choice of half the country off the ballot would spark a “fury [that] might not be limited to verbal protests or marches.”

If Biden is re-elected merely because Trump has been disqualified by a pivotal secretary of state (in Michigan, say, or Wisconsin), “the rage and chaos that would follow are beyond imagining,” the Atlantic’s David Frum argues. “And then what? If Section 3 can be reactivated in this way, then reactivated it will be,” he adds, predicting that Republicans would then try to disqualify choice Democrats and on and on and on.

Some of the above questions are legalistic. This one strikes at the very heart of America’s political order. It’s not impossible that, within a matter of months, we will be faced with producing answers for all of them.

More news to know.

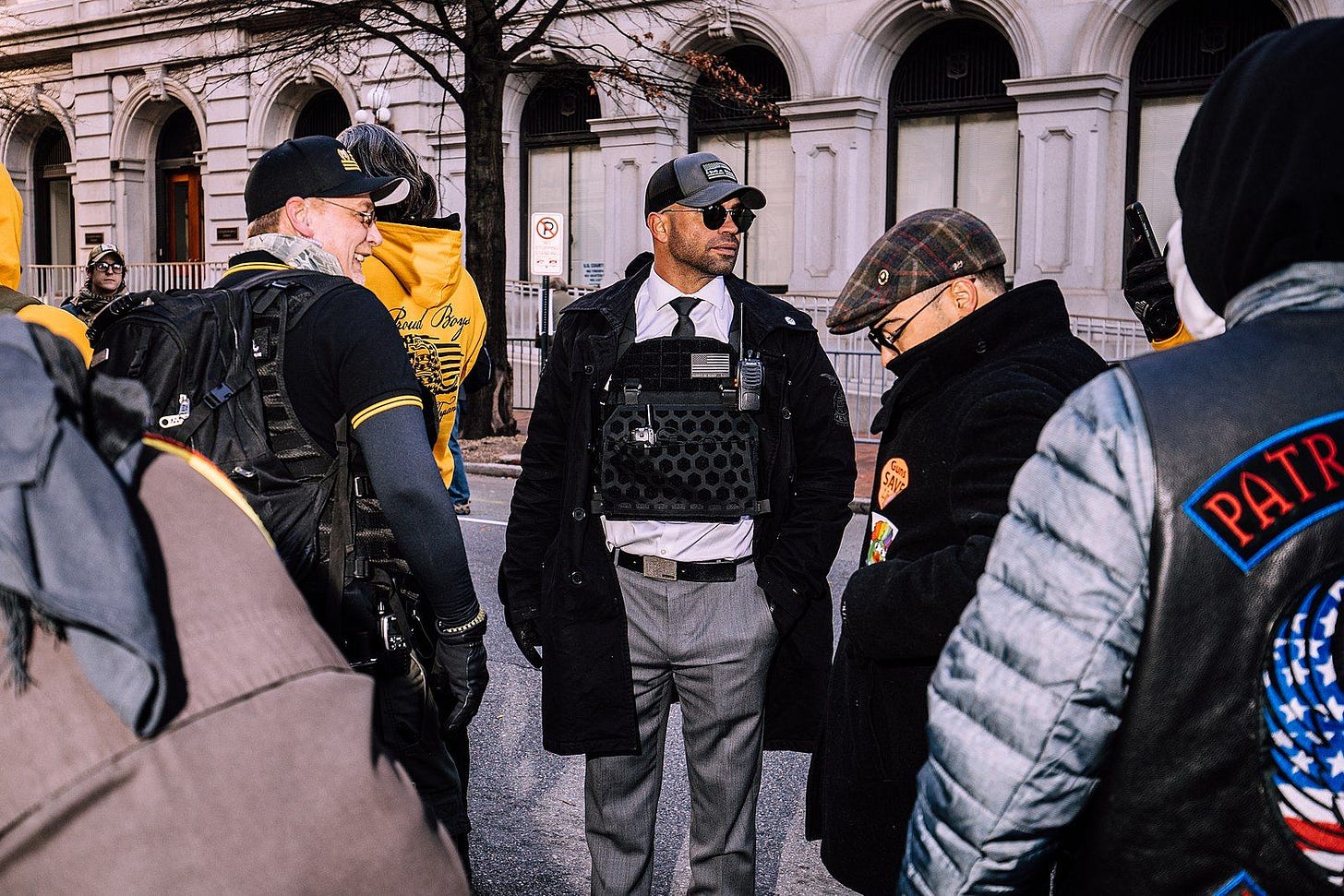

Proud Boys leader Enrique Tarrio was sentenced to 22 years in prison for his role in the January 6th riot, the harshest penalty yet tied to the attack. (CBS News)

Rhode Island Democrats nominated former Biden aide Gabe Amo in a crowded special primary election for a safe-blue seat, picking him over a left-wing candidate endorsed by Bernie Sanders and AOC. Meanwhile, a special primary election in Utah remains too close to call. (NBC News)

A federal appeals court threw out Alabama’s redrawn congressional district map, ruling that it failed to comply with a Supreme Court order to give Black voters more electoral power. (AL.com)

Chinese nationals have “accessed military bases and other sensitive sites in the U.S. as many as 100 times in recent years,” including by posing as tourists or even scuba divers. (Wall Street Journal)

Michigan Republicans scored a top recruit this morning when former Rep. Mike Rogers announced his plans to run for the state’s open Senate seat next year. (Detroit Free Press) On the Democratic side, “Tennessee Three” state Rep. Gloria Johnson launched a challenge against GOP Sen. Marsha Blackburn. (The Tennessean)

4 million borrowers have enrolled in President Biden’s new income-driven student loan repayment plan, the Education Department announced. (The Hill)

George Santos appears to be considering a guilty plea in his criminal fraud case. (New York Daily News)

Special Counsel Jack Smith warned in a filing that Donald Trump has made “daily extrajudicial statements that threaten to prejudice the jury pool.” (CNN) Meanwhile, Smith’s efforts to access Rep. Scott Perry’s (R-PA) cell phone data were partially blocked. (Politico)

Out of the country’s 94 federal district courts, 25 have never had a non-white judge. (Bloomberg Law)

Medicare costs are no longer skyrocketing — and no one quite knows why. (New York Times)

U.S. officials say Congress has left “gaping holes in the country’s national security” after letting a federal program to protect chemical facilities from terrorists expire in July. (Associated Press)

Mike Pence is feuding with Vivek Ramaswamy (Politico), while Kamala Harris is locked in a “cold war” with Gavin Newsom. (The Messenger)

What to watch today.

All times Eastern.

At the Capitol: Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-KY) will hold his first press conference since his August freezing incident, where he will likely face questions about his health and his future atop the Senate GOP. The congressional physician reported Tuesday that there is no evidence linking McConnell’s episode to a seizure disorder, stroke, or Parkinson’s disease — although the doctor did not offer an alternative explanation.

The Senate is also scheduled to vote on the confirmation of three Biden nominees: Philip Jefferson (to be Fed vice chair), Lisa Cook (to be a Fed governor), and Gwynne Wilcox (to be a member of the National Labor Relations Board).

At the White House: President Biden will deliver remarks at 2:15 p.m. celebrating the new West Coast dockworkers contract, which was ratified last week after acting Labor Secretary Julie Su brokered talks between the unions and the dock operators. The six-year contract, which ensured that ports from California to Washington State could remain open, includes a 32% pay increase for the workers.

Around the world: Vice President Harris is in Jakarta, Indonesia, for the biannual Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) summit. As the AP notes, the trip — her third to southeast Asia — is “another opportunity for Harris to burnish her foreign policy credentials,” particularly as a spokesperson on countering China, the topic that is expected to dominate the summit.

Meanwhile, Secretary of State Antony Blinken is in Kyiv, Ukraine, where he arrived for a surprise visit this morning. Blinken is expected to announce a new military aid package for Ukraine and receive briefings on the country’s three-month-old counteroffensive, which has made only limited progress.

In Atlanta: Former President Donald Trump and his 18 co-defendants in the Fulton County, Georgia racketeering case were scheduled to be arraigned today. However, all 19 of them pleaded not guilty in advance and waived their right to appear at an in-person arraignment.

Instead, Judge Scott McAfee — who is overseeing the case — is holding a hearing this afternoon on motions filed by defendants Kenneth Chesebro and Sidney Powell to sever their cases from the others.

On the campaign trail: In New Hampshire, former Vice President Mike Pence will deliver a 2 p.m. address — billed by his campaign as a “major speech” — to warn the Republican Party against choosing populism over conservativism.

Before I go...

Here’s a piece that stuck with me: Mark Leibovich’s remembrance of Bill Richardson — the former New Mexico governor and Clinton-era Cabinet member who passed away on Friday — in The Atlantic.

The piece features a litany of great anecdotes about Richardson, from his Guinness World Record for hand-shaking (13,392 hands in eight hours) to the time Leibovich told Richardson that he was on his list of favorite politicians to write about (“How high on the list?” Richardson asked in response).

It continues into a meditation from Leibovich — a veteran political journalist — on when politics was fun, as exemplified by Richardson. “I do love politics,” Richardson once said. “I love to campaign. I love parades. I don’t believe I’m pretentious. I’m very earthy... I’m sick of all these politicians these days who are always trying to convince you that they are not really politicians.”

Leobovich writes:

I’ll admit that the notion of a pol who loves the game seems quite at odds with the tenor of politics today. People now routinely toss out phrases like our democracy is at stake and existential threat to America, and it’s not necessarily overheated. Fun? Not so much. But thinking about Richardson makes me nostalgic for campaigns and election nights that did not feel so much like political Russian roulette.

Thanks for reading.

I get up each morning to write Wake Up To Politics because I’m committed to offering an independent and reliable news source that helps you navigate our political system and understand what’s going on in government.

The newsletter is completely free and ad-free — but if you appreciate the work that goes into it, here’s how you can help:

Donate to support my work or set up a recurring donation (akin to a regular subscription to another news outlet).

Buy some WUTP merchandise to show off your support (and score a cool mug or hoodie in the process!)

Tell your family, friends, and colleagues to sign up at wakeuptopolitics.com. Every forward helps!

If you have any questions or feedback, feel free to email me: my inbox is always open.

Thanks so much for waking up to politics! Have a great day.

— Gabe