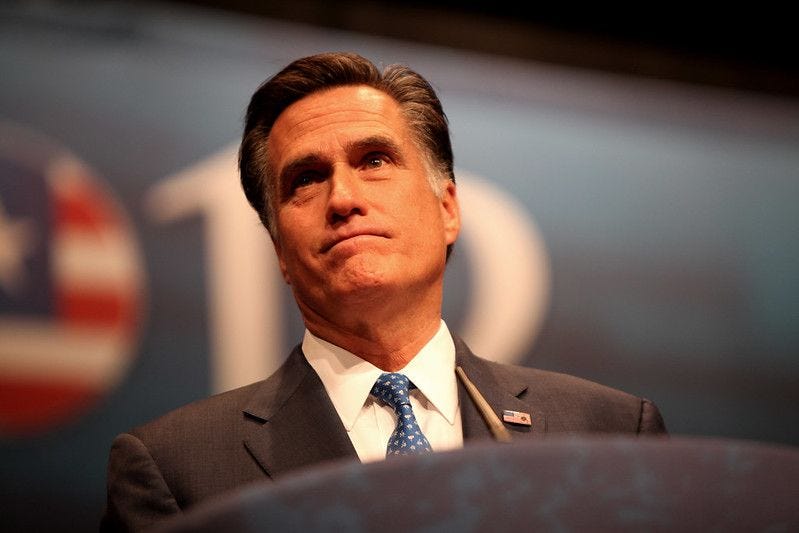

Most Democrats may now share a general respect for Sen. Mitt Romney (R-UT), who announced plans to retire on Wednesday, but that wasn’t always the case.

If you think back to 2012 — it can be hard, I know — the reality is that Democrats ran a fairly bruising campaign against Romney, the Republican presidential nominee that year.

As Politico reported at the time, even in the midst of a nasty fight for the presidency, Obama and his top aides stuck out for engaging “far more frequently in character attacks and personal insults than the Romney campaign.” The article goes on:

Romney has maintained that Obama is a bad president. . . [but] not made the case that Obama is a bad person, nor made a sustained critique of his morality a central feature of his campaign. . . Obama, who first sprang to national attention with an appeal to civility, has made these kind of attacks central to his strategy. The argument, by implication from Obama and directly from his surrogates, is not merely that Romney is the wrong choice for president but that there is something fundamentally wrong with him.

Think of the TV ad tying Romney to a woman’s death from cancer or the one where a worker accused Romney of effectively making him build his own coffin.

Those attacks, of course, were nothing compared to the level of revulsion the left then felt towards Senate Republican Leader Mitch McConnell (R-KY).

McConnell’s pledge to make Obama a “one-term president,” combined with his commitment to blocking progressive priorities (and later, a Supreme Court nomination), led to Democrats labeling him the “grim reaper” of the Senate graveyard. Few Republicans made Democrats’ blood boil like McConnell.

Listen to Democrats talk about Romney and McConnell in 2023 — two impeachments, four presidential indictments, and a Capitol riot later — and you’d be excused if you had trouble remembering they’re referring to the same two men.

After McConnell’s most recent freezing episode last month, a procession of Democrats were seen physically embracing the Kentuckian on the Hill; even more have spoken to the press about their hopes that McConnell will stay in office, which would be a shocking sentiment to 2012 ears.

Yesterday, when Romney announced his plans to step down, President Biden — who famously told a Black audience in 2012 that Romney would “put y’all back in chains” if elected — called to commiserate, just as he dialed up McConnell after both of the senator’s freeze-ups.

Former Biden chief of staff Ron Klain, who was the architect of many of the Democratic attacks on Romney as head of Obama’s 2012 debate prep, mournfully wrote on X that Romney “will be missed by all people of good will in public life.”

However much they may have despised the duo in the past, Democrats will miss Romney and McConnell when they’re gone.

It isn’t just that the two look good compared to Trump and his band of MAGA backup singers. They have also been crucial grist in the legislative mill these past few years, either helping draft (Romney) or giving critical support (McConnell) to compromises on infrastructure, manufacturing, gun control, electoral reform, and other issues.

The hollowing-out of the Senate’s moderate core is a story that has been written, in increments, for years. (Here’s a Brookings Institution report on the matter from back in the 1990s.) But with McConnell severely diminished and Romney going the way of Jeff Flake, Bob Corker, and countless other Senate centrists, the odds are now increasing that the bipartisanship of the early Biden era may have been nothing more than a brief experiment, a blip on the country’s path to polarization.

Take, for example, the 10 senators who crafted the bipartisan infrastructure package earlier in Biden’s term. Romney is retiring, poised to be replaced with someone to his right. Rob Portman already left, leading Ohio to trade one of the Senate’s leading Republican dealmakers for the populist firebrand J.D. Vance. On the Democratic side, a key trio — Joe Manchin, Kyrsten Sinema, and Jon Tester — all hail from vulnerable seats and could face political extinction next year. (If they even run: Manchin is reportedly flirting with decamping to lead West Virginia University; Sinema has yet to announce her plans.)

That leaves the Democratic duo Jeanne Shaheen and Mark Warner, plus Republicans Susan Collins, Lisa Murkowski, and Bill Cassidy, none of whom are less than 65 years old.

If you’re wondering what the Senate will look like once these old-timers call it quits, you don’t need to look far.

Just take a walk across the Capitol, to the House of Representatives, where the Republican majority is now effectively run by a small group of right-wing members. Just this week, Speaker Kevin McCarthy has been cowed into announcing an impeachment push and forced to pull a routine defense spending package from the floor — a possible preview of what the Senate may look like before long.

Trends in the Senate have long followed those in the House, where, after all, many of its members are derived from. “No stream can be purer than its sources,” Woodrow Wilson once wrote. “The Senate can have in it no better men than the best men of the House of Representatives; and if the House of Representatives attract to itself only inferior talent, the Senate must put up with the same sort.”

The ideological movements in the House tend to trickle up to the Senate over time, as they slowly build to the point of statewide support. The Senate is often seen as reserved for a different kind of politician — more elite, more stately — but it is nothing more than a lagging indicator for our politics. “There cannot be a separate breed of public men reared specially for the Senate,” Wilson wrote; if a certain group is in the House in enough numbers, you can be sure they will eventually make their way across the Capitol.

We see this already with polarization in the two chambers. Since around the 1980s, the House has been more polarized — as calculated by the difference between the average DW-NOMINATE ideological scores of the two parties in the chamber — but the Senate isn’t far behind, and the gap is closing fast:

Again, it’s no mystery why: the moderates are leaving, either by defeat or retirement (or retirement because they know they’ll be defeated).

This is a problem in both parties, but particularly on the Republican side. The following chart also uses DW-NOMINATE, isolating out the percentage of the Senate Democratic and Republican caucuses with scores considered “moderate.” As you can see, Manchins and Sinemas are a rare breed — but Romneys are the Senate’s real endangered species:

Up until now, small as they might be in numbers, Senate GOP institutionalists have formed a powerful bulwark in Washington.

Even as many House Republicans have clamored for an end to Ukraine aid, called for a Biden impeachment, and practically cheered on a government shutdown, the vast majority of Senate Republicans have made their opposition clear on each count.

Senate GOPers from McConnell on down have scoffed at the idea of impeachment and worked with Democrats on bipartisan spending bills to fund the government, just as far greater numbers of Senate than House Republicans backed the Biden era’s previous bipartisan accomplishments.

There’s no guarantee this will remain as true come 2025, after voices like Romney’s have left the stage. On Ukraine aid, for example — an issue both McConnell and Romney are particularly passionate about — many of the Senate GOP’s top recruits have adopted the House GOP’s isolationist tone, including Tim Sheehy in Montana and Sam Brown in Nevada.

The Romney equivalents in many states — Chris Sununu of New Hampshire, Larry Hogan of Maryland — have opted against Senate runs, both giving stemwinders about Senate gridlock when they did. Ben Sasse is another example of a less dug-in Republican who left the Senate in frustration, leaving to take a university job and furthering the Senate brain drain. (After Romney joins Sasse, Pat Toomey, and Richard Burr in retirement, four of the 10 Republicans who voted to convict Trump after January 6th will have left the Senate in just four years.)

If the Republican presidential primary has made visible the party’s move from Reagan-era conservatism to Trump-era populism, the GOP’s Senate field shows that the last redoubt of Reaganism left — the Senate Republican conference — may also be in its dying days.

Signs of the Senate GOP’s House-like future are already cropping up. McConnell, who has been a constant since 2007 while House Republicans cycled through three different speakers, faced his first-ever leadership challenge earlier this year, mimicking the constant leadership struggles among Republicans in the lower chamber.

When McConnell does join Romney in retirement, his most likely replacements — John Thune and John Cornyn — are relative institutionalists as well: Thune has battled with Trump too, Cornyn helped craft the bipartisan gun bill last year. But they will likely have a looser grip on the conference than the steely McConnell, leading to more House-style freelancing like has already been seen this year with Tommy Tuberville.

One close observer, Romney, minced no words on Wednesday when asked which way the GOP was trending. “It’s pretty clear that the party is inclined to a populist demagogue message,” Romney told the Washington Post. (In a forthcoming biography, he puts it even starker: “A very large portion of my party really doesn’t believe in the Constitution.”)

Still, he said, he has not given up hope. “If it can change in the direction of a populist,” the Utah senator added, “it can change back in the direction of my wing of the Republican Party.”

If that happens, though, Romney will no longer be in Washington to be a part of it.

Thanks for reading Wake Up To Politics this Thursday morning. The Iowa caucuses are 123 days away. The 2024 elections are 418 days away. I’m not retiring any time soon: tell your friends to sign up here for the newsletter. If you want to contribute to support my work, you can donate here.

More news to know.

House punts on Pentagon bill, an ominous sign as shutdown looms (WaPo)

DACA struck down again, but protections remain for current recipients (Axios)

Judge temporarily halts New Mexico governor’s gun restrictions in Albuquerque (Politico)

The day ahead.

At the White House: President Biden will hold a “Bidenomics” event in Largo, Maryland. VP Harris will launch a nationwide college tour with an event at Hampton University in Virginia.

In the Senate: The upper chamber will hold a procedural vote on a “minibus” appropriations package covering funding for the Departments of Agriculture, Veterans Affairs, Transportation, and Housing and Urban Development.

In the House: The lower chamber will consider the Preserving Choice in Vehicle Purchases Act, which would block a California rule blocking the sale of gas-powered gars after 2035.

Thanks for reading.

I get up each morning to write Wake Up To Politics because I’m committed to offering an independent and reliable news source that helps you navigate our political system and understand what’s going on in government.

The newsletter is completely free and ad-free — but if you appreciate the work that goes into it, here’s how you can help:

Donate to support my work or set up a recurring donation (akin to a regular subscription to another news outlet).

Buy some WUTP merchandise to show off your support (and score a cool mug or hoodie in the process!)

Tell your family, friends, and colleagues to sign up at wakeuptopolitics.com. Every forward helps!

If you have any questions or feedback, feel free to email me: my inbox is always open.

Thanks so much for waking up to politics! Have a great day.

— Gabe