SCOTUS Plunges Back Into the Culture Wars

Inside the courtroom for two transgender sports cases.

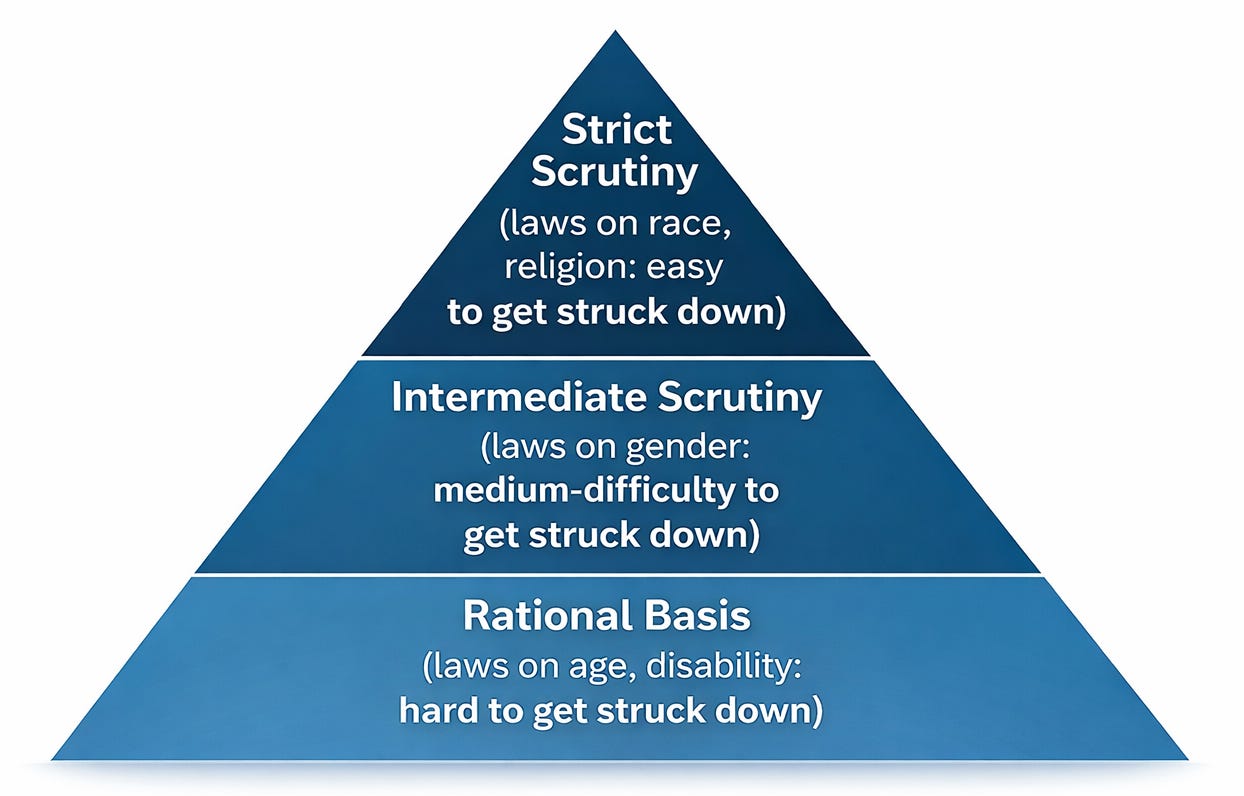

All men are created equal, but not all civil rights cases are.

Colloquially, when we think of “civil rights,” we often lump together developments involving race, gender, religion, and other identities. But legally, not all of these categories are treated the same.

When statutes are challenged under the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment — which says that “no state shall…deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws,” forming the bedrock of American civil rights law — federal courts use a system of several tiers.

The highest tier is called “strict scrutiny.” These are the laws that are, well, scrutinized most strictly. When a court applies this standard, the government can only win if it proves that a given law is absolutely necessary to achieve a “compelling state interest.” This is a hard test to pass, and most laws considered in this tier are struck down.

Laws only receive strict scrutiny when they potentially discriminate against so-called “suspect classes,” of which the Supreme Court has only recognized four: race, national origin, religion, and alienage.

Sex isn’t one of them. Instead, the court has deemed it a “quasi-suspect class,” which means laws that impinge on sex fall under the next tier: “intermediate scrutiny.” Here, a state only has to prove that a law fulfills an important state interest, an easier bar to pass. A law in this category can still get overturned, but it has a better chance of being upheld than one considered under strict scrutiny.

Finally, there’s the last tier: “rational basis review.” Unlike strict scrutiny, where the presumption is that a law will be struck down (unless the government can go the extra mile and prove otherwise), here the default is that a law will be upheld (unless the challengers can go the extra mile and prove otherwise). Laws touching identities like age and disability fall under this less closely restricted tier.

This system has been in use since the 1930s, when it was first initiated by the justices through — what else? — a lowly footnote.

Where do laws that interact with LGBT identities fall into all of this? How harshly should those be treated? The Supreme Court has never said.

On Tuesday, this question came before the justices yet again, in a pair of cases concerning West Virginia and Idaho state laws that require students to play on sports teams that match their biological sex. Little v. Hecox was the Idaho case, brought by Lindsay Hecox, a transgender woman who wanted to join the women’s track and cross-country teams at Boise State University. The other case was West Virginia v. B.P.J., brought by Becky Pepper-Jackson, a transgender girl who wanted to join girl’s track and cross-country at her middle school.

As far as the constitutional challenge to the state laws go, the key questions are about which identity groups are being impinged on here and which level of scrutiny should apply.

The states argue that these laws have nothing to do with gender identity; it has to do with sex. “Idaho’s law classifies on the basis of sex because sex is what matters in sports,” the state’s lawyer, Alan Hurst, told the justices on Tuesday. And neither sex was discriminated against by the law, he added: “It treats all males equally and all females equally regardless of identity.”

He argued that intermediate scrutiny should not apply, since the only classification in the law was sex-based and the challengers were not questioning that classification (i.e., they were not pushing back against the idea of sex-segregated sports). Even if the court did use an intermediate scrutiny test, Hurst added, the law should be upheld. This is because of a key difference between intermediate and strict scrutiny: while strict scrutiny requires that laws surrounding race be “narrowly tailored,” intermediate scrutiny allows for laws surrounding sex to have a bit more flexibility.

In other words, courts view any sort of law that divvies people up by race with inherent suspicion. (It’s strict scrutiny, remember.) But divvying up by sex? That could be necessary depending on the context, courts have said (with one acceptable context being school sports). Because of that, states get a bit more flexibility in intermediate scrutiny world. “Idaho’s law is a substantial fit for 99 percent of males, and a perfect fit is not required,” even under intermediate scrutiny, Hurst pointed out.

“Even if you assume the heightened level of scrutiny, let’s assume that we’re in intermediate scrutiny world, it’s still a reasonable fit,” West Virginia lawyer, Michael Williams, said of that state’s law. And a “reasonable fit” is all that’s required by intermediate scrutiny.

The challengers to the two state laws view things differently, of course. Kathleen Hartnett, representing Hecox, argued that transgender people should be treated as a quasi-suspect class, and that the Idaho law discriminates against them. The question shouldn’t be are men and women treated equally under the law, she said: it’s whether transgender and cisgender people are.

But even if the court doesn’t agree there, Hartnett also argued, the law should fail on the basis of discriminating by sex. Hartnett stressed that her client underwent hormone therapy that lowered her testosterone levels, which she argued erased any biological advantage Hecox might have over cisgender girls. This means that the law does discriminate on the basis of sex, because it treats “transgender women without any biological advantage” (as she views it) differently than an “untalented cisgender boy” who also lacks an athletic advantage.

“He would have the same sex-based advantage, the circulating testosterone,” Hartnett said. “He just would not be as good at sports.”

This leaves the justices with several options. Heading into Tuesday’s hearing, attorneys on both sides urged the justices to decide, once and for all, whether transgender people form their own “quasi-suspect” class and should receive intermediate scrutiny on their own terms, whether the question is about whether a law discriminates on the basis of gender identity, not merely on the basis of sex.

The justices could take them up on it, and either rule that transgender people meet the criteria for a quasi-suspect class or not, and then that the state laws either survive or don’t depending on that ruling.

But, from my perspective, the court seemed a lot more likely to rule that the state laws only impinge on sex, not gender identity, and handle the laws on those grounds, declining to either create a legal category for transgender people or rule one out and rather sidestepping the question entirely.

Justice Brett Kavanaugh repeatedly signaled that he would prefer to handle the cases at the statutory level, focusing on whether the bans violate Title IX (which governs sex-segregated sports teams) instead of answering the 14th Amendment question. “Given that half the states are allowing it, allowing transgender girls and women to participate, about half are not, why would we at this point…jump in and try to constitutionalize a rule for the whole country?” Kavanaugh asked, especially when many of the scientific questions undergirding the case are still being debated.

The conservative justices seemed likely to construe the laws as only concerning sex, and then to uphold them on those grounds. Picking up on the states’ argument that the laws were a reasonable fit for the vast majority of students — which is all that’s required to satisfy intermediate scrutiny — Chief Justice John Roberts pressed the challengers on whether they were really “transforming intermediate scrutiny to strict scrutiny.”

“That sounds an awful lot like strict scrutiny,” Roberts added. “Or, unless you’re going to say whenever you can come forward with anything that is an exception to the boy/girl distinction, any case at all, you can go forward with a strict scrutiny challenge, whether it’s 1 percent or whether it’s 12 people, and I’m just not quite sure [I’m] grasping why your position isn’t really an effort to apply strict scrutiny to a distinction that we haven’t applied it to.”

Justices Samuel Alito, Clarence Thomas, and Amy Coney Barrett appeared ready to join them as well.

One conservative justice, Justice Neil Gorsuch, has played the role of swing justice on these issues, having authored the 2020 majority opinion in Bostock v. Clayton County (which ruled that the Civil Rights Act prohibits employment discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation or gender identity, as a form of sex discrimination) and also joined last year’s majority opinion in United States v. Skrmetti (which upheld a state law banning puberty blockers and hormone therapy for transgender minors did not violate the Constitution because it isn’t sex discrimination).

In neither of these cases did the court touch the question of whether transgender identity forms a quasi-suspect class of its own, only addressing the questions through the lens of sex discrimination.

Gorsuch was the only conservative justice who seemed interested in possibly going down this path, asking Idaho’s lawyer to respond to the argument that “transgender status should be conceived of as a discrete and insular class subject to scrutiny, heightened scrutiny, in and of itself, given the history of de jure discrimination against transgender individuals in this country over history in immigration and family law, cross-dressing statutes, they get a long laundry list.”

The other conservatives, however, seemed unlikely to take this step, particularly without a definition of what it means to be transgender, which the lawyers for the two challengers both declined to offer. “And what is that definition?” Alito repeatedly asked. “For equal protection purposes, what does it mean to be a boy or a girl or a man or a woman?”

The liberal justices, meanwhile, seemed to be participating in defense mode, recognizing that their colleagues were likely to uphold the state laws and trying to nudge them towards the narrowest possible holding. Of the two cases, the lower courts only spoke to the constitutional questions in the Idaho case — and there, Hecox made a last-minute push to dismiss her case by arguing it was now moot since she no longer plans to play college sports.

Justice Sonia Sotomayor seized on this point, arguing that the court shouldn’t “force an unwilling plaintiff” to bring a case, since “having a case named after you makes your infamy live forever.” Justice Elena Kagan, meanwhile, pushed the court to make a limited ruling that might preserve the laws but rule they are unconstitutional as applied to these specific plaintiffs, since the plaintiffs had both undergone therapies to reduce their competitive advantage.

While the conservative justices didn’t seem prepared to make a ruling that was so broad as to address the constitutional questions, they also didn’t seem likely to offer a holding that was so limited as to only apply to the plaintiffs, or the small group of transgender people without a competitive advantage.

As Roberts said, that seemed to be pushing the court towards strict scrutiny world, where every specific application of a law is scrutinized closely to ensure it doesn’t sanction discrimination. In intermediate scrutiny world, however, some edge cases are acceptable, which the court seemed poised to recognize.

Personally, one of the striking things about Tuesday’s arguments was how civil they were: it isn’t often you see transgender issues being calmly debated, with recognition of how complicated they are. “I’ve been wondering what’s straightforward after all this discussion,” Justice Gorsuch said at one point during the marathon arguments, which stretched to last three and a half hours.

Although the room contained its share of culture warriors — attorney Chase Strangio, who received blowback even from the left for pushing too far in his argument of the Skrmetti case, was there, and conservative journalist Megyn Kelly was sitting near me in the press section — the arguments seemed to show a maturation for both sides on these issues.

Alan Hurst, the lawyer for Idaho, acknowledged the “significant discrimination against transgender people in the history of this country.” (Justice Gorsuch, referencing a Supreme Court case that was part of that history, noted that it “perhaps not our finest hour.”) Kathleen Hartnett, the attorney challenging the Idaho law, was asked by Justice Alito if she thought people who raise concerns about transgender women participating in women’s sports are “bigots” or “deluded,” Hartnett responded: “No, Your Honor. I would never call anyone that.”

When Alito asked her about a hypothetical transgender aspiring student-athlete who has not received the sort of hormone therapies her client had received, Hartnett said that she would “respect their self-identity in addressing the person” but broke with some LGBT activists by conceding the person could have a “sex-based biological advantage that’s going to make it unfair for that person to be part of the women’s team.”

Notably, the conservative justices referred to “trans girls,” acknowledging their gender identity and earning derision from the right. “I hate that a kid who wants to play sports might not be able to play sports,” Justice Kavanaugh, a girl’s basketball coach said, seemingly referring to transgender and cisgender athletes alike.

Sports are often “zero-sum,” he added, and a transgender girl making a team might mean a cisgender girl will not. “And so one way to resolve it, as you say, is the facts, try to figure out is there really a competitive advantage,” Kavanaugh said. “I think we’re going to get a lot of scientific uncertainty about that, a lot of debate about that, a lot of different district courts.”

It’s rare to hear that level of nuance in public conversations, acknowledging harms that might be had on either side — and waiting to hear more evidence before throwing in one’s lot.

Which made it all that much more jarring to walk outside, where two rival protests had been going on — one in favor of the state laws, and one opposed to them. Away from the staid discussions of strict and intermediate scrutiny, any nuance fell away as I exited the courtroom. At one point, a speaker on one side yelled “No puberty blockers in girl’s sports! No puberty blockers in girl’s sports!” into a microphone, while demonstrators on the other chanted, “We’re here! We’re queer! We’re here! We’re queer!”

It was a literally ear-splitting representation of the fierce public divide on this issue — and the significant gulf the court is wading into by taking it up yet again.

Appreciate hearing the historical and legal context of these proceedings. Also, thanks for being our boots on the ground!

Outstanding analysis and commentary Gabe. I am center to left but have always had my concerns about transgender girls competing in girls sports

I was especially happy to see the justices addressing is from a biological/physical perspective. Everything’s else is histrionics