Playing Constitutional Hardball

Two worrying signs from this week.

I conducted an interview a few years back that I never ended up using for the newsletter. It was with Mark Tushnet, a progressive legal scholar and Harvard law professor.

Tushnet, a former clerk for Thurgood Marshall, is known for his writings on comparative constitutionalism, judicial review, and many other topics. But I wanted to talk to him about a 2004 paper of his, influential in its own right, that had recently been stuck in my mind.

“For the past several years I have been noticing a phenomenon that seems to me new in my lifetime as a scholar of constitutional law,” Tushnet opens the paper. “I call the phenomenon constitutional hardball.”

When we spoke in 2023, here’s how Tushnet described the concept. “The basic idea about constitutional hardball,” he told me, “is that there are assumptions about how our constitutional system works that are not written down in the Constitution, but they sort of become the accepted ways of doing things.”

“Constitutional hardball,” he continued, “involves ignoring those accepted ways of doing things, by doing things that are pretty clearly permitted by the Constitution but aren’t sort of within the bounds of normal political behavior.”

When he first wrote about this phenomenon in 2004, Tushnet’s examples included the Republican impeachment of Bill Clinton (it was “clearly constitutionally permissible” but “stretched the idea of ‘high crimes and misdemeanors’ beyond what had been assumed in the past,” he told me) and the Democratic filibusters of George W. Bush’s judicial nominees (which themselves morphed into the “accepted ways of doing things,” before eventually filibusters for nominations were snuffed out altogether).

Almost two decades later, I wanted to quiz Tushnet about more recent political debates, from Democratic proposals to pack the Supreme Court to Republican threats not to raise the debt ceiling, to see how well they matched up with his theory. For the most part, Tushnet didn’t think I was raising very good examples.

“Politicians try out lots of things all the time, including ideas that are — to use the technical term — wacko,” he told me. “And most of the time, the wacko ideas go nowhere. And the fact that a politician is pursuing one of these ideas is of no real significance. It’s only when it gets real purchase that it’s something that the constitutional system needs to pay attention to.”

For that matter, not even attempts to overturn the 2020 election qualified as constitutional hardball, Tushnet said, because they’d been so roundly unsuccessful. “There’s nobody who lost an election who has nonetheless taken office,” he pointed out.

I never ended up doing anything with the interview. But, two years later, Tushnet’s concept is once again on my mind — less because I’m interested in parsing out whether specific examples qualify, but more because I think it’s helpful to have language around events in the news you might be noticing.

I’m thinking of two examples in particular:

Redistricting

In the normal political model, the U.S. census takes place every decade, in the year ending in “0” (e.g. 2020). The population count is then used to apportion the 535 congressional districts among the 50 states, and state legislatures go about drawing their new district lines. These lines are used for the first time in the election year ending in “2” (e.g. 2022) and then continue to be used until the next one (e.g. 2032).

Neither the Constitution nor any federal law prevent states from revisiting their congressional district lines in the middle of the decade. It just hasn’t normally been done.

This week, the Texas legislature has convened for a special session. Gov. Greg Abbott (R-TX) has laid out 18 agenda items he wants the legislators to consider; redistricting, even though we aren’t coming up on a year that ends in “2,” is one of them.

Abbott was reportedly hesitant to ask for this, but President Trump has pushed the state’s Republicans to take a second look at their district lines mid-decade. He wants the new map to produce five additional Republican seats, Punchbowl News has reported.

Rescissions

In the normal political model, each year, Congress passes 12 appropriations bills that fund the government by September 30. OK, fine, the real normal is that Congress passes an “omnibus” package combining all of these bills, and basically never by September 30, operating off of a “continuing resolution” until then.

But still: be it separate appropriations bills, or a mega-package, or a CR, the relevant normalcy for our purposes today is that all of these types of funding vehicles are subject to the Senate filibuster, which means they require 60 votes, which means (if neither party has that number of seats) that members of both parties have to support the funding measure for it to pass. Even in highly polarized times, then, our normal political model guarantees some measure of bipartisanship for Congress’ most important task: deciding annually how much money each arm of the government should get.

The rescissions process — by which the president can request that Congress allow him not to spend everything appropriated in the most recent funding bill — is perfectly legal, just like mid-decade redistricting. But, because a rescissions bill requires only 51 votes, it represents a potential threat to the normal order of the appropriations process.

You could have funding be approved by 60 votes, under a compromise negotiated between both parties. But then one party, with just 51 votes, could undo the parts of the compromise they didn’t want.

Republicans recently approved a rescissions package for the first time in decades, clawing back $9 billion in funds for foreign aid and public media. Now, Democrats are raising concerns about entering into a new funding deal for the next fiscal year, without assurances that Republicans won’t use another rescissions package to undo it.

Rescissions and mid-decade redistricting, just like impeaching a president or (when it was possible) filibustering a judicial nominee, aren’t inherently dangerous. You can easily imagine scenarios where it makes sense to do any of them.

They also aren’t new: Rescissions date back to the 1970s, and Republican attempts to mid-decade redistrict in Colorado and Texas in the 2000s is actually one of the examples of constitutional hardball that Tushnet cited in his original paper.

But the spirit in which something is being done matters. Many previous rescissions packages were bipartisan; the 2000s-era attempts at mid-decade redistricting, at least, had a putatively apolitical motive (the Colorado and Texas lines that were being redrawn then, unlike the Texas lines being redrawn now, had been originally drawn by courts, so it’s perhaps unsurprising that the state legislatures wanted to take another crack at drawing the lines themselves).

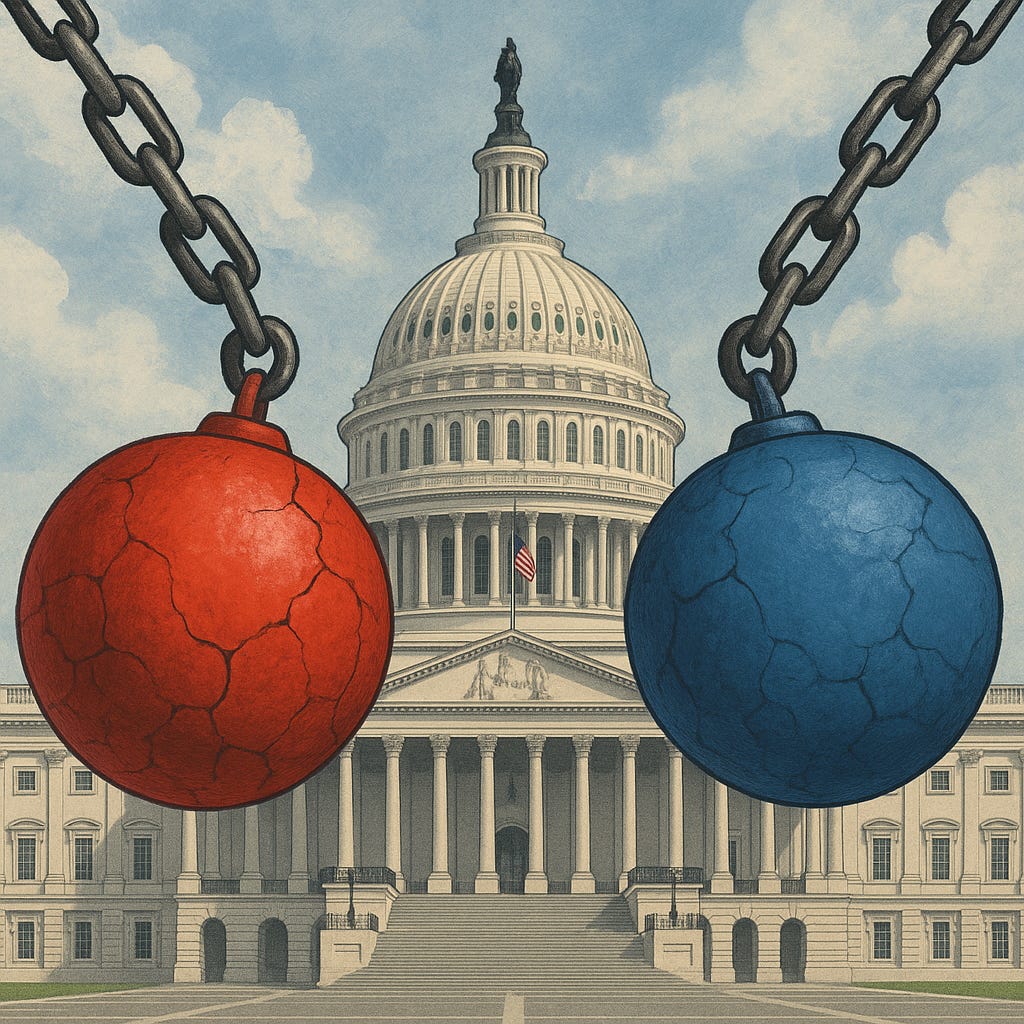

The potential responses to an action also matter. At the end of the day, I’m not sure I fear constitutional hardball as much as I fear constitutional ping-pong: each party taking turns dismantling a political norm when they’re in power, until norm after norm have disappeared.

In the redistricting case, it’s already clear how that could happen. “Two can play this game,” Gov. Gavin Newsom (D-CA) wrote last week about the Texas redistricting plan, threatening to try to redraw California’s district lines to benefit Democrats if Texas implements a new map that benefits Republicans. Democrats are also exploring states like New York, New Jersey, Minnesota and Washington responding in kind; Republicans, in turn, are also considering mid-decade efforts in states like Ohio, Missouri, and Florida.

Pretty soon, state after state could have their congressional district lines gerrymandered to the max, with each side trying not to spare any change that could yield a partisan advantage.

Appropriations ping-pong wouldn’t be pretty either. If the new normal becomes that parties undo 60-vote spending deals with 51 votes, we could be headed for a breakdown in the government funding process. “Why would I trade baseball cards with my friend if he tells me ‘I’m gonna break into your house tomorrow night and steal my cards back’?” Sen. Chris Murphy (D-CT) said in a recent interview.

It could make shutdowns even more normal and, eventually, lead to the filibuster being done away with for appropriations bills altogether (just like what happened with nominations). White House budget director Russell Vought, who crafted the GOP rescissions package and has promised more of them, seemed to forecast this outcome with his recent comments: “The appropriations process has to be less bipartisan. It’s not going to keep me up at night, and I think will lead to better results, by having the appropriations process be a little bit partisan.”

In his 2004 paper, Tushnet noted that the solution to constitutional hardball is for “political constitutional actors to behave like grown-ups.”

“So, for example,” he wrote, “the solution to the problem created by the tie vote in the 2000 presidential election — one that would be obvious in other democratic constitutional systems — would have been the negotiation of a coalition government, with some agreement, perhaps memorialized in a coalition document, about which Cabinet offices each party would control, with assurances that, taken as a whole, the portfolios of the Democrats and Republicans would be roughly equivalent in social and political importance.”

Of course, that solution did not come to pass.

In a piece picking up on Tushnet’s concept, two legal scholars wrote in 2018 of politicians playing “anti-hardball,” by adopting changes like independent redistricting commissions that reduce the political pressures on important processes.

Depressingly, though, one of the states now considering retaliatory mid-decade redistricting (California) has an independent redistricting commission; Newsom is proposing doing away with it. The filibuster is also arguably a tool to inject bipartisanship into an otherwise political process (passing laws). It, too, seems close to extinction.

As the Trump administration continues to push the Overton window of actions available to a president (and to their allies on the state level), the coming years will be crucial for seeing which direction our country takes. Trump has opened up a suite of precedents that will be tempting for the next president (Democrat or Republican) to grab, from freezing congressional spending to suing media companies to broadening the aperture of what is possible under the reconciliation process.

His presidency could be followed by an “anti-hardball” moment, not unlike the post-Watergate period, when the two parties came together to renegotiate the social contract of what “normal political behavior” looked like, reining in executive power. Maybe doomsday prophecies like maximum gerrymandering or constant shutdowns will look like “wacko” possibilities, just like the 2023 proposals Tushnet and I discussed that mostly were not adopted.

Or redistricting and appropriations wars do take place, and the Trump era sets off a protracted game of constitutional ping-pong, going back and forth, back and forth, until “normal political behavior” slowly becomes unrecognizable. This would happen over a long period of time, and it’s possible that things have to get worse to get better (like the reforms that could only be unlocked by Watergate). Our best hope, Tushnet told us more than 20 years ago, is political actors behaving like grown-ups. Not exactly a great sign.

It is a sad day when we can’t expect our elected officials to act like grownups. But I’m afraid that day has arrived. Great newsletter, Gabe. As always, keep up the great work.

Interesting piece. Many of the problems cited by playing “ constitutional hardball” is that our form of government does not operate like a parliamentary system. While there are many flaws to parliamentary government, there is much less need for “ workarounds” to the system itself. For example, the filibuster itself was created as a means to prevent civil rights legislation from passing ( a very bad motive). Over time it became a tool to prevent majority votes from even coming to the floor of the Senate, even to the point of not allowing for discussion of a bill. We already have a body that is unrepresentative of the country with two Senators for each state regardless of population. Adding and using the filibuster in this way has made it worse because each party’s motives are suspect. In the end, we have a human system where we need a significant number of people who agree to play by certain rules most of the time, whether they be codified or just strong norms. If we have players whose main objective is to totally disable the other player, as I feel the Republican Party as currently constituted wants to do, then very soon we will have no game left to play.