GOP fights fire with paper

The perils of a party animated more by personality than policy.

Good morning! It’s Monday, October 23, 2023. The 2024 elections are 379 days away. If this newsletter was forwarded to you, subscribe here. If you want to contribute to support my work, donate here.

Have you ever wondered why House Republicans call themselves a “conference” while House Democrats refer to themselves as a “caucus”?

If you’ve never noticed this subtle semantic split, take a look at how both parties present themselves on Twitter:

Historically, the difference was that a “caucus” had the ability to bind its members to vote a certain way, while a “conference” was a more informal gathering of lawmakers. House Republicans made the switch away from a caucus in 1911, after “Czar” Joe Cannon’s iron-fisted reign as House speaker ended. (Cannon is the only House speaker other than Kevin McCarthy to face a motion to vacate vote, although he survived the ouster effort.)

Today, both parties are somewhere in between: neither has any binding requirement that its members vote in lockstep, but an expectation still persists that lawmakers toe the party line.

Throughout modern history, for example, members of both parties have cast protest votes for the speakership without punishment. (Over the years, everyone from John Lewis to Colin Powell has received an errant vote for speaker.) But a caucus-like norm still persisted that a member’s vote for speaker would be cast for whoever their party nominated behind closed doors, even if it wasn’t their first choice — and especially if the nominee couldn’t squeak through without their help.

The fundamental problem facing House Republicans right now is that their current conglomeration of 221 members subscribes to no such norm, true to the “conference” label. In January, 20 conservatives violated the norm to oppose McCarthy. Then, last week, 25 of their colleagues — mainly from the other side of the GOP ideological spectrum — violated the norm to oppose Jim Jordan. Hence the past 20 days without a speaker.

Republicans face a similar problem on the presidential level, where a norm once existed that losing presidential primary candidates would embrace their party’s nominee even after a bruising primary. But, for the past seven years, Donald Trump has threatened to stomp all over that expectation, holding the GOP hostage to the possibility that if they deny him the nomination, he will tank the party’s hopes of a White House victory.

To both these problems, the Republican Party’s leaders have come up with an unassailable solution: pieces of paper.

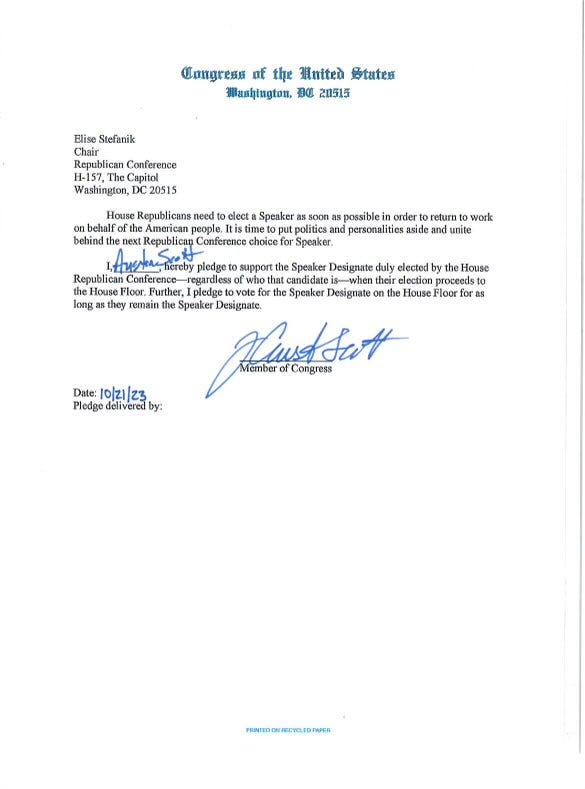

Over the weekend, a “unity pledge” began floating around the Capitol, committing Republican speaker candidates to supporting the party’s eventual nominee for the post:

Some rank-and-file House Republicans have even begun signing a second pledge, promising to support a candidate for speaker if they agree to sign the first pledge.

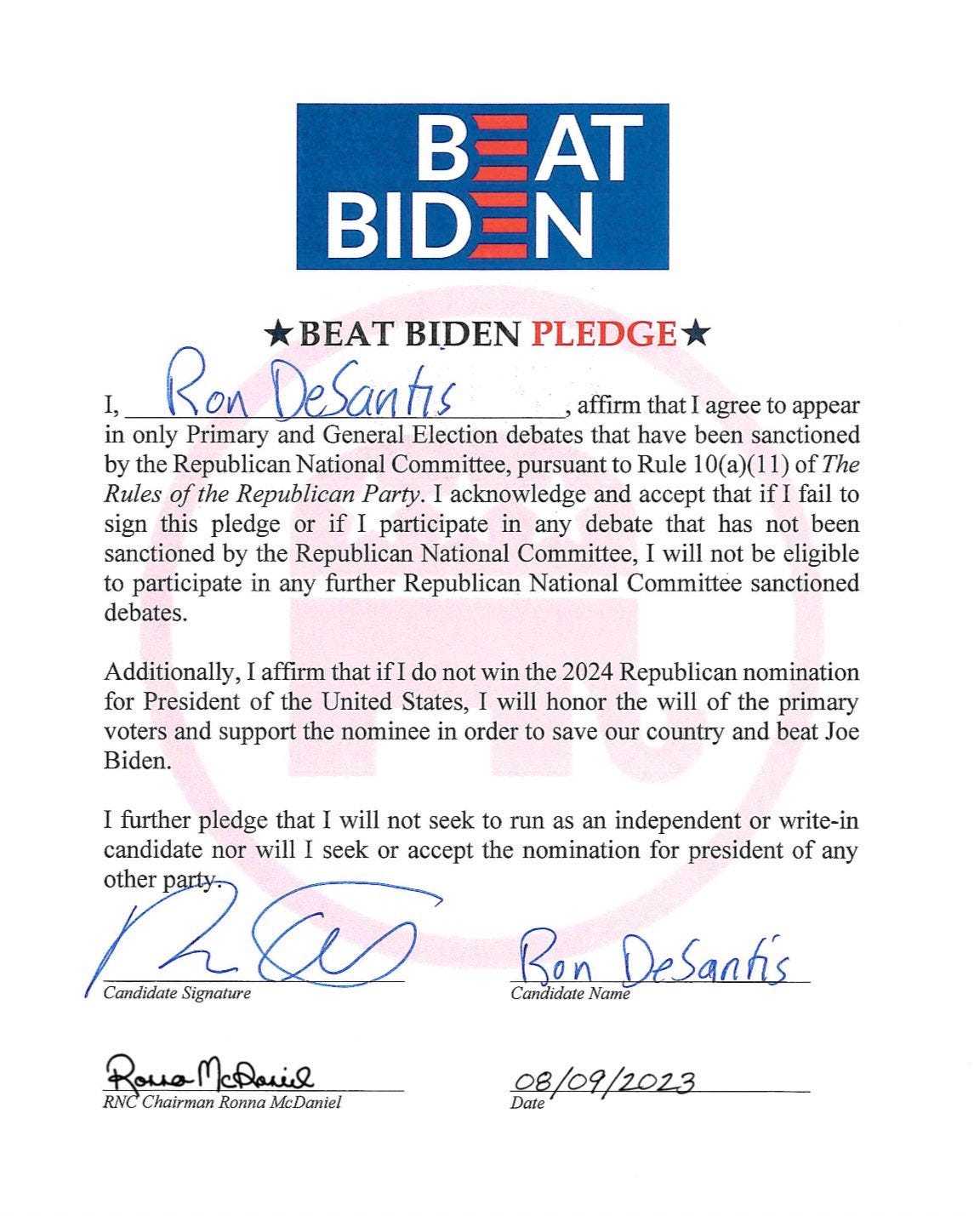

This effort is not dissimilar from the pledges that the Republican National Committee has asked its presidential candidates to sign, affirming that they will support the GOP nominee in 2024:

But unity pledges are a poor substitute for genuine party unity.

As I’ve noted previously, the Republican Party once sat atop Ronald Reagan’s “three-legged stool”: social conservatives, fiscal hawks, and foreign interventionists. Trump blatantly swore off the latter two legs (and has had a shaky-at-best relationship with the first), but never put forward an equivalent policy agenda for the party to rally around, except for fealty to Trump himself.

Political parties are never completely aligned on policy, of course. Yet, they have traditionally been built on the foundation of what political scientist V.O. Key called a “concert of interests,” a melding of priorities not unlike the Reagan-era stool. Trump, in 2020, ran for president without a party platform; if the modern GOP still has a definable “concert of interests,” he has shown no interest in defining it.

Similarly, on Capitol Hill, today’s Republican rebels differ from their predecessors like Newt Gingrich in that their crusades are almost always over personality, not policy. “Whereas Gingrich had an infectious vision of what America ought to be about and was bursting with ideas about how to fix up the government, his successors seem dour and unimaginative in their pugnacity,” AEI’s Phillip Wallach recently wrote in The Atlantic, depicting a band of lawmakers more interested in fighting for fighting’s sake.

In this era of peak negative partisanship, it is perhaps easier to construct a party based on enmity towards your rival party than it is to design a positive policy platform for yourself. This is true to some degree of both parties — fear of Trump will drive the vast majority of Democrats to vote for Joe Biden in 2024, for example, even though most don’t want him to run again — but it is particularly acute within the GOP, where dislike for the other party is slightly larger and uniting policy beliefs (at least judging by the lack of a 2020 platform) are noticeably fewer.

In Congress, opposition as a motivating unifier is easily sustained in the minority, when lawmakers can pass their days reflexively voting “no” on the other party’s proposals. But that falls apart in the majority. When Democrats held slim congressional majorities from 2021 to 2023, they led one of the most productive Congresses in recent memory, due to a relatively strong — but obviously imperfect — shared sense of policy direction. When Republicans held slim congressional majorities from 2017 to 2019, the first two years of the Trump era, the party led one of the least productive modern Congresses, failing even to unite around a health care policy that had been, for a decade, its top campaign promise.

And now, of course, Republicans once again hold a slim majority in half of Congress, and that half has spent the last two weeks shut down by its own dysfunction.

Instead of focusing on putting together a new “concert of interests,” Republicans on the congressional and presidential levels are prolonging the inevitable by churning out meaningless “unity pledges,” oaths of loyalty to personality without any common loyalty to a set of higher principles that might help avoid crises like the speaker-less House from occurring.

On top of that, the pledges are, of course, completely non-binding, lacking any power to actually constrain Republican candidates for president or for speaker. “King Caucus” this is not.

The RNC unity pledge was invented in the first place to block Donald Trump from launching an Independent bid for president in 2016 if he lost the nomination. Trump signed the thing, but made abundantly clear he would ignore it if he wanted to. (The pledge ended up constraining his rivals, not him, since they felt honor-bound to support him in the general election after signing it.)

This time around, Trump has declined to even sign the RNC pledge, meaning — in all likelihood — each of his rivals have agreed to support a nominee who has thumbed his nose at the chance to offer the same courtesy to them. In other words: they got played.

Manufactured unity, the type a pledge provides, isn’t needed when party members already trust and agree with each other — but it is doubly worthless when they don’t.

Texas Rep. Chip Roy, a Republican who declined to sign the speakership unity pledge, cited that lack of trust in explaining his decision to demur.

“The average American Republican does not, justifiably, trust the majority of the GOP simply for the sake of it - [or that] without verification it will do what it said it will do… which it rarely has done,” Roy wrote.

Moments of in-party transition — when trust ebbs, and new motivating commonalities must be found — are not new in American politics. Sometimes, they have led to parties breaking up (see: the Whigs), but more often, they have simply led to parties evolving into something slightly different, as the Republicans are in the midst of doing now.

At different periods in history, it has been the Democrats who have faced these same exact troubles. “Republicans fall in line, Democrats fall in love,” the old saying goes; “I am not a member of any organized political party,” the humorist Will Rogers joked in the 1930s. “I am a Democrat.”

More recently, there were the Hillary Clinton supporters in 2008 — known as “PUMAs,” short for “party unity, my ass” — who famously refused to vote for Obama in the general.

In 2020, Democrats defused a similar movement of Bernie Sanders voters by putting together something more tangible than a unity pledge: a set of “unity task forces,” teams of Biden and Sanders allies who worked together to hash out a party platform agreeable to both sides.

It is hard to imagine groupings of Trump and DeSantis surrogates, for example, doing the same thing. Who would participate? What issues would they focus on? Because their differences largely come down to personality, they are at once too vast and too vague to resolve. Too vast because the person at the top of the ticket would be the one thing that couldn’t be negotiated; too vague because there are ultimately few nitty-gritty policy disputes between them. On the ones that exist, neither side would be likely to budge, in contrast to the Biden and Sanders camps, who had larger policy gaps but shared a more serious policy focus that at least gave them somewhere to negotiate from.

In the House, Kevin McCarthy and Matt Gaetz attempted a “unity task force” of their own at the beginning of this Congress, when they tried negotiating a plan to run the House. We all know how that turned out.

Such are the perils of a party coalition more motivated by opposition than support, led by an individual with few firmly held beliefs or principles. House Republicans may elect a new speaker this week, but without a shared sense of purpose or direction, their troubles — and the party’s — are likely only starting to brew.

More news to know.

Gaza gets some aid — but no fuel — as power crisis upends lives / WaPo

How Two American Hostages Were Set Free From Gaza / NYT

House GOP speaker race balloons to nine candidates / Axios

Trump fined $5,000 for violating gag order, as judge threatens jail for future violations / Politico

Back-to-back plea deals pose grave legal threat to Donald Trump / CNN

The day ahead.

White House: President Biden will deliver remarks at 2:15 p.m. ET to announce 31 regional tech hubs funded by the CHIPS and Science Act.

Congress: The Senate is out until tomorrow. House Republicans will meet at 6:30 p.m. ET for a candidate forum to hear from the party’s nine contenders for speaker.

Courts: Sen. Bob Menendez (D-NJ) will appear in court this afternoon, where he is expected to plead not guilty to federal charges alleging that he acted as an agent of the Egyptian government while serving as chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee.

Thanks for reading.

I get up each morning to write Wake Up To Politics because I’m committed to offering an independent and reliable news source that helps you navigate our political system and understand what’s going on in government.

The newsletter is completely free and ad-free — but if you appreciate the work that goes into it, here’s how you can help:

Donate to support my work or set up a recurring donation (akin to a regular subscription to another news outlet).

Buy some WUTP merchandise to show off your support (and score a cool mug or hoodie in the process!)

Tell your family, friends, and colleagues to sign up at wakeuptopolitics.com. Every forward helps!

If you have any questions or feedback, feel free to email me: my inbox is always open.

Thanks so much for waking up to politics! Have a great day.

— Gabe