Haley wins the Koch primary

Is the party deciding on Nikki Haley? Or is it too little, too late?

Good morning! It’s Wednesday, November 29, 2023. The 2024 elections are 342 days away. The Iowa caucuses are 47 days away. If this newsletter was forwarded to you, subscribe here. If you want to contribute to support my work, donate here.

There are two main ways to conceive of presidential primaries.

The simple way is the one you probably learned in civics class: Iowa votes, then New Hampshire, then the rest. At the end, the candidate with the most delegates wins. We’ll call that “The Voters Decide.”

In 2008, a group of political scientists proposed a different theory, known as “The Party Decides.” In this conception of presidential nominations, the important part is not Iowa or New Hampshire, but the stage that comes before it — the stage we’re in now — which they call the “invisible primary.”

Instead of foregrounding the choices of actual primary voters, this theory focuses on party insiders — lawmakers, activists, etc. — and suggests that their endorsements are generally determinative of who wins a party’s presidential nod.

This influential book — with a plume of smoke on the cover, calling to mind the “smoke-filled rooms” of yesteryear — quickly became Gospel for political scientists and pundits.

Then, of course, it all came crashing down. Come 2016, when Donald Trump — decidedly not the choice of Republican Party insiders — was nominated, the tome was widely mocked; Nate Silver called it “the most-cited and the most-maligned book” of that election cycle.

I’ve actually had one of the authors, Hans Noel, as a professor at Georgetown, and he gamely admitted in class that he and his fellow scholars got some things wrong. But he also argued that the theory had been misapplied: it’s not as though Republican insiders in 2016 coalesced behind a different candidate and Trump went on to beat them. Instead, the party just never decided.

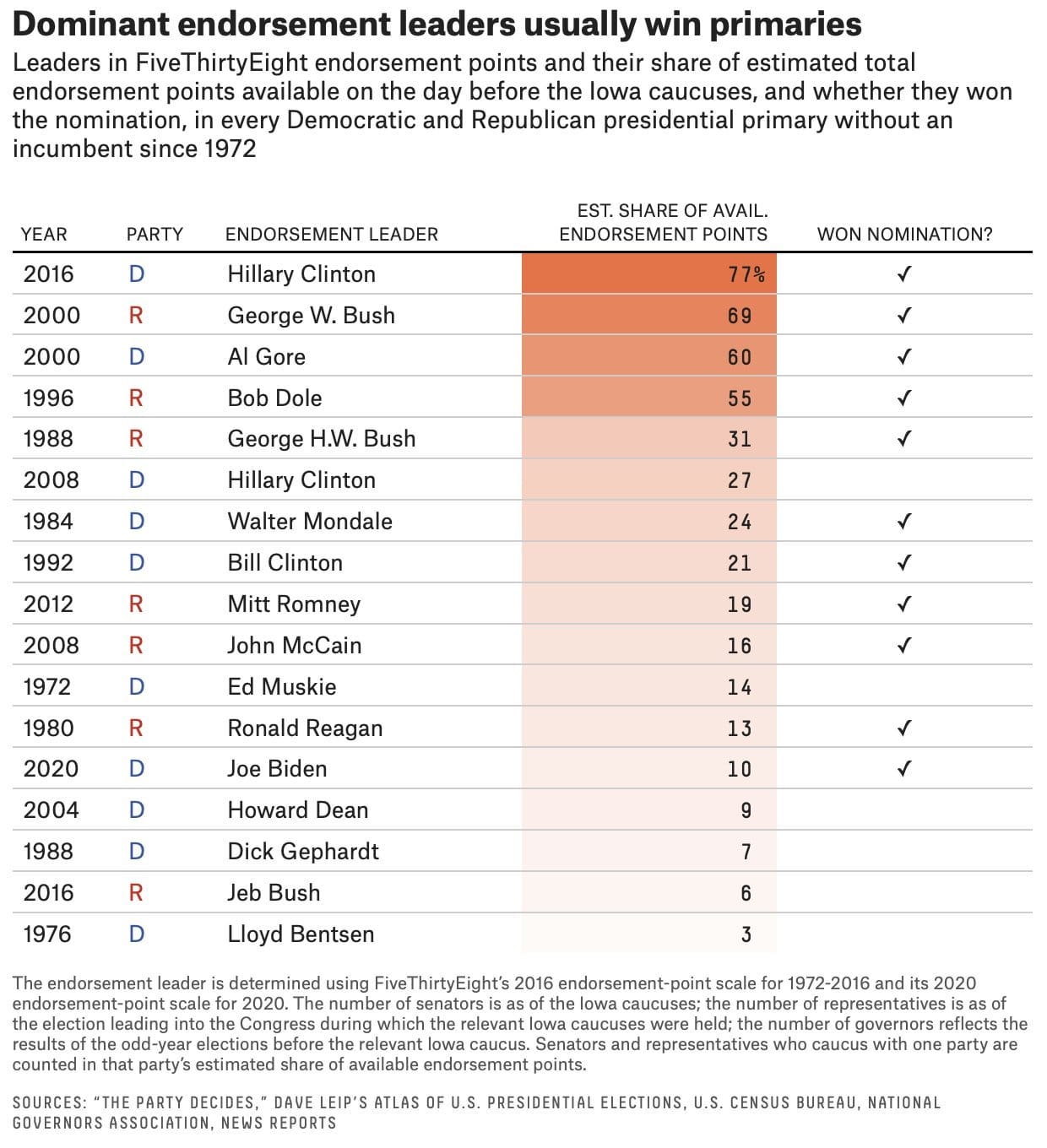

For an example of what he meant, here’s a FiveThirtyEight count of how many party leaders backed the “endorsement leader” in each “invisible primary” dating back to 1972. You’ll notice that Jeb Bush, the most-endorsed GOP contender in 2016, sits all the way at the bottom, supported by a paltry 6% of the available endorsers.

Sure, Donald Trump was not the choice of Republican leaders in 2016 — but if you remember Jeb Bush (or anyone else) as the consensus pick of these individuals, you’re misremembering. The truth is the party never got its act together to bless an anti-Trump alternative, which is part of why the reality TV star was able to coast to victory.

The theory in “The Party Decides” relies on these types of coordination games among party leaders: their belief is really that whoever the party coordinates to back ahead of time will generally win; they weren’t wrong in 2016 so much as the party ended up opting not to coordinate.

Flash forward eight years and, once again, many Republican insiders do not want Donald Trump to be the party’s nominee. Once again, they aren’t really coordinating to achieve that goal.

Not surprisingly, per FiveThirtyEight, the vast majority of GOP leaders who have endorsed a presidential candidate have picked Trump himself. But the rest — the Republican leaders opposed to Trump, your Brian Kemps or Mitch McConnells — have almost uniformly declined to throw their firepower behind a candidate, once again choosing not to decide instead of deciding wrong.

After four years in the wilderness, though, the Republican donor class — which is even less in touch with the GOP base than the political class — has been less content to remain on the sidelines. Determined to block a Trump renomination, GOP bundlers have been showering money on his rivals.

The clearest sign of this came Tuesday, as Americans for Prosperity Action — the powerful donor network founded by the billionaire brothers Charles and David Koch — endorsed Nikki Haley’s bid for the White House.

This is a stark change from 2016, when the Koch brothers opposed Trump in the primaries but decided not to endorse an alternative, epitomizing the party’s coordination problem. In a move that angered some of their donors, the Kochs merely outlined their top five GOP contenders that year (Trump wasn’t on the list) and left it at that, deciding not to pick among them. Clearly, that strategy didn’t work out.

“We know to elect better leaders, we need better candidates,” AFP Action wrote in a Tuesday memo announcing their Haley nod. “And that means we need to engage earlier and in more primaries. As the presidential candidates set the tone for the entire election — we decided earlier this year to start our work in primaries at the top of the ticket: the Republican presidential primary.” (That last line is an implicit rejection of the group’s 2016 decision to focus on Senate races and sit out the presidential.)

AFP Action’s nod is no small thing: yesterday, Axios called it “the most important endorsement of the GOP primary so far.” The group isn’t just a donor network: it has a powerful on-the-ground presence, which it says is the “largest grassroots operation in the country.” For Haley, this endorsement unlocks an army of thousands of door-knockers and phone-bankers, plus an enormous war chest to finance direct mail and advertising.

But is it enough to solve the GOP’s stubborn coordination problem?

This is outside the scope of “The Party Decides” — this kind of thing happens after the “invisible primary” — but another way to look at the same issue is the behavior of the candidates themselves.

Perhaps the best recent example of such party-level coordination comes courtesy of the 2020 Democrats, when a number of moderate candidates (Pete Buttigieg, Amy Klobuchar, Beto O’Rourke) were determined to stop Bernie Sanders from winning the nomination, and (with nudging from key party leaders) consolidated behind Joe Biden.

Scott Walker famously encouraged the 2016 Republicans to take this same approach, but they didn’t take his advice. Over Thanksgiving break, I read McKay Coppins’ excellent new biography of Mitt Romney, which devotes several pages to Romney’s efforts in 2016 to encourage the GOP field to coordinate.

Romney’s idea was for the candidates to split up the states they were strongest in, agreeing not to compete in each other’s territory in order to deny Trump the maximum amount of delegates in each contest, setting up a brokered convention. Twice in 2016, GOP candidates came close to pulling off this type of alliance; both times, the efforts would quickly be ruined by John Kasich, who emerges as one of many villains in the Romney book.

Coppins writes:

The plan, while a long shot, was strategically sound and, Romney thought, the best chance any of these candidates had to wrest the nomination from Trump. It was simple math — any rational person could see it. But as Romney would soon be reminded, presidential candidates are not always rational actors.

Trump rivals today could attempt a similar “Romney strategy” (although I wouldn’t suggest they call it that). Ron DeSantis could take Iowa, where he was recently endorsed by the state’s governor; Nikki Haley could take New Hampshire, where the governor will likely endorse her soon.

Then they could each take their home states — delegate-rich Florida and early-state South Carolina, respectively — and divvy up the rest of the map from there. But, logically sound as it might be, the idea is as unlikely now as it was then.

One key test will be where all of Haley’s Koch money actually flows to. In the group’s memo, AFP Action’s decision is explicitly described as a move to stop Trump from winning the nomination. But that will require using the money differently than Haley has used her funds so far.

Consider this, from the New York Times:

Ms. Haley’s allied super PAC has spent $3.5 million on ads and other expenditures attacking Mr. DeSantis in the last two months in Iowa and New Hampshire, according to federal records, but not a dollar explicitly opposing Mr. Trump despite his dominant overall lead.

Haley’s barrage of attacks against DeSantis, which have been met with a similar blitz from his direction, have succeeded in inching her support up to his level — but meeting your rival at around 10% is little consolation when the leading candidate is sitting at about 60%. In Politico yesterday, Jack Shafer compared the Haley/DeSantis jockeying to the “Playoff Bowl,” the short-lived NFL competition between the league’s two second-place division finishers. Congrats! You’re the winner of the losers.

The Koch endorsement is a sign of some coordination at the donor level, and funders like Miriam Adelson and Ken Langone could follow. The party writ large might still not be deciding, but at least some powerhouses that never backed a horse in 2016 are doing so now.

It’s too early to say for sure — remember, the 2020 Dem consolidation happened in March; this is still the previous November — but so far, nothing similar has happened on the candidate level. (It certainly hasn’t on the party leader level. Haley boasts a grand total of one congressional endorsement.)

Even more than in 2016, his rivals are unlikely to organize around stopping Trump, because they simply don’t view it as their No. 1, drop-everything priority. “I think Governor Haley and I both have the same goal, and that is to be president of the United States,” Chris Christie (a top contender to be this cycle’s Kasich) said recently, dismissing the idea of forming an anti-Trump alliance.

Partially, this is a function of Trump’s much stronger starting position within the party, and the fact that announcing a stop-Trump mission would probably lead to a candidate losing Republican support more than gaining it. But it is also the result of years of built-up, pro-Trump muscle memory: the idea of his nomination is no longer viewed as an urgent, must-stop crisis by many in the party, including those running against him.

In 2016, candidates like Ted Cruz, Marco Rubio, and Lindsey Graham talked that way about a Trump nomination, even if they didn’t act on it. In 2024, his rivals are neither talking nor acting like it, making eventual coordination unlikely. Instead, they are pouring resources into beating each other up, acting as though their main opponent simply does not exist.

To paraphrase Mitt Romney, presidential candidates are not rational actors.

More news to know.

Negotiators Press for Long Term Israel-Hamas Truce / WSJ

Even Most Biden Voters Don’t See a Thriving Economy / NYT

Republicans mount 11th-hour push for George Santos to resign / Axios

Rosalynn Carter honored by family, friends, first ladies and presidents, including husband Jimmy / AP

Georgia prosecutors oppose plea deals for Trump, Meadows and Giuliani / The Guardian

The day ahead.

President Biden will deliver remarks at CS Wind in Pueblo, Colorado, the world’s largest wind tower manufacturer, selling his economic agenda right in Lauren Boebert’s district.

First Lady Jill Biden will unveil a White House ice skating rink for the holidays.

The Senate will vote on confirmation of two district judge nominees.

The House will begin consideration of the Protecting our Communities from Failure to Secure the Border Act, which would prohibit the National Park Service, the Bureau of Land Management, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, and the Forest Service from housing migrants on federal land.

The Supreme Court will hear oral arguments in Securities and Exchange Commission v. Jarkesy, a case that could upend the structure of the SEC — and other government agencies.

Thanks for reading.

I get up each morning to write Wake Up To Politics because I’m committed to offering an independent and reliable news source that helps you navigate our political system and understand what’s going on in government.

The newsletter is completely free and ad-free — but if you appreciate the work that goes into it, here’s how you can help:

Donate to support my work or set up a recurring donation (akin to a regular subscription to another news outlet).

Buy some WUTP merchandise to show off your support (and score a cool mug or hoodie in the process!)

Tell your family, friends, and colleagues to sign up at wakeuptopolitics.com. Every forward helps!

If you have any questions or feedback, feel free to email me: my inbox is always open.

Thanks so much for waking up to politics! Have a great day.

— Gabe