The truth about Gen Z

Also, I’m a college graduate!

Hi all,

First things first: I graduated from college on Saturday. Yay!

I know I said the newsletter would be back this week, but I underestimated just how tired I would be after the weekend and how much time it would take to move to a new apartment. So WUTP will returning in full force next week, not today. Sorry! However, in lieu of a normal newsletter, I do have some thoughts I wanted to share this morning...

Perhaps because it’s graduation season, I’ve been receiving a lot of media requests lately about a similar collection of topics: the Class of 2024, how we were impacted by Covid, how that’s shaped our politics, what the Gen Z vote will look like in November.

I talked to The New Yorker about all this a few days ago for a forthcoming article; last night, after my parents went home and in between goodbyes with friends, I went on WNYC for an episode on these same themes.

Over the years, I’ve gotten used to being asked by other reporters to talk about my generation, which many media outlets seem to treat as an enduring mystery and source of fascination. I even like to think I’ve gotten my spiel down pretty good. But, the truth is, I hate talking about Gen Z in politics.

For one thing, succinctly summarizing the attitudes and ideologies of 70 million Americans is nearly impossible. Generations are grouped together by media outlets for understandable ease (and they often do share some important commonalities), but they are just as varied and complex as any other large collection of people. At the end of the day, I am just one person, with a specific set of thoughts and experiences and peers. My lived sense of Gen Z’s politics might be entirely different than another 22-year-old’s across the country, which is why I hate being asked broad questions about the whole generation and having to give an answer as if it’s representative of people I’ve largely never met and who think wildly different from one another.

Also, whenever I’m asked to do that kind of thing, I always get the sneaking suspicion that I’m being asked to confirm one of two ideas that the interviewer has already decided on: either that Gen Z is politically disengaged and disillusioned or that we are fired up by politics and poised to change the world. Perhaps like every generation of young people, adults have all sorts of ideas they are constantly trying to project onto Gen Z, often in an attempt to wedge us into a larger narrative that just so happens to serve their political interests.

Yesterday, I tried to say some of this on WNYC, but only had a few minutes (such is the nature of live radio!) — so I wanted to share the rest of what I had to say here.

For me, the most frustrating thing about hearing people talk about Gen Z is how much it feels like they are just going off vibes, even though there is abundant data available that can tell us about young people with more accuracy than I or any one else’s individual experiences possibly could.

During the WNYC show last night, they asked various students and teachers from the Class of 2024 to describe how our generation is unique. They received answers asserting we are more “empathetic” than previous generations, more “introspective,” etc. Which, maybe? It is very difficult to quantify an entire generation’s level of empathy or introspection.

Then there are things that are very easy to quantify. One of the other guests on the program, who hosts a podcast for WBEZ (the public radio station in Chicago), said that Gen Z is more intentional than other generations about where we put our money, in that we are more likely to donate to causes we believe in or boycott companies we oppose.

That sounds very nice in theory, but it’s easy to check if that’s true, and — spoiler alert — it’s not. According to the Harvard Youth Poll, one of the few large-scale surveys of Gen Z Americans, just 13% of 18- to- 29-year-olds have donated to a political campaign or cause in the last 12 months. 84% have not. When you put the same question to all Americans, regardless of generation, you get basically the same result. Per PRRI, 39% of Gen Z adults have avoided buying a particular brand in the last 12 months. For all American adults, that number is 38%. Gen Z is no more or less political with our money than anyone else.

If you asked young Americans who describe themselves as “politically engaged” these same questions, those numbers are slightly higher — but that brings me to my next gripe about Gen Z coverage. So much of it seems to go off “vibes,” and the people who set the vibes are usually the ones who are highly engaged and visible: the protesters, the activists, the news junkies. In short, people like me, who have made politics a big part of their daily life.

But those people are not representative of Gen Z politically. According to the Harvard poll, 27% of Gen Z says they are “politically engaged or politically active.” 72% say they are not. The media generally allows the thoughts and beliefs of one-fourth of the generation to drive coverage of the other three.

It’s important to note that the 27% number does not mean Gen Z is unusually engaged or disengaged, as varying groups try to make us out to be. It means we’re normal. Revealingly, it’s hard to find a poll that asks all adults the same question about engagement (the engagement levels of young people seems to be a fascination for adult pollsters; not so much the engagement levels of adults, even though it’s equally important). But, if we take the percentage of Americans who tell Gallup they follow political news “very closely” as a rough proxy, we end up with 32% — which seems to suggest that Gen Z is about as engaged as anyone else, not extraordinarily more or less. In addition, media outlets often report about turnout surges among young voters, like in 2018 and 2020, but those surges generally just track turnout increases among other groups.

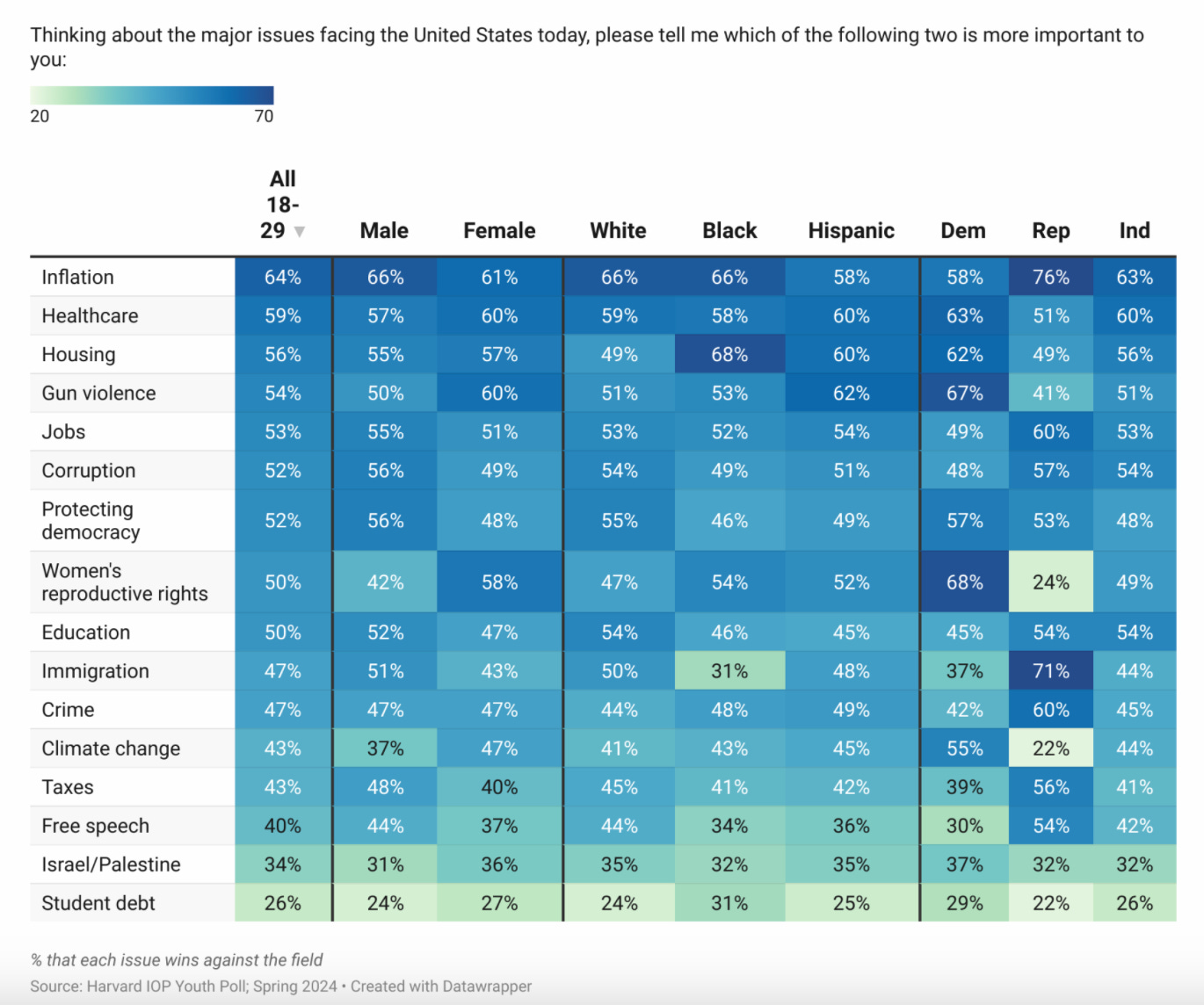

In general, I feel like media outlets — and campaigns, too — tend to particularize young voters way too much, probably because they spend too much time observing the vibes and not enough reading the data. Based on the vibes emanating from the most engaged Gen Z’ers, you might think that issues like climate change, student loans, and the Israel/Gaza war are the most important ones to young voters. Certainly, they make up a hefty portion of media coverage of the Gen Z vote, and they are often the issues campaigns use to target 18- to- 29-year-olds.

But, in fact, when you ask young people about the most important issues to them — as Harvard did last month — student loans ends up dead last. Israel/Palestine is second-to-last. Climate change is towards the bottom. The three most important issues to young people are inflation, health care, and housing. In other words: the same core issues that all Americans say are important to them. There isn’t a special set of issues to reach young voters. Young voters are a lot more like everyone else than anyone cares to admit.

It may not be particularly interesting to say that on the radio or in a news article — “Gen Z Political Engagement Similar To Other Generations” doesn’t make a very titillating headline — but the data tells us in many ways it’s true. Media outlets and political campaigns that over-particularize young voters, based on the specific issue sets and activism of the highly engaged subset, do so at their peril.

According to Harvard, 14% of young people have attended a political rally or demonstration in the last 12 months. 82% have not. It’s very easy for reporters to walk to a climate protest or a demonstration over Israel/Gaza, interview a few young people, and decide they’ve heard the voice of a generation — but, in fact, they’ve only heard from the 14%, leaving the vast majority of young people out of the picture.

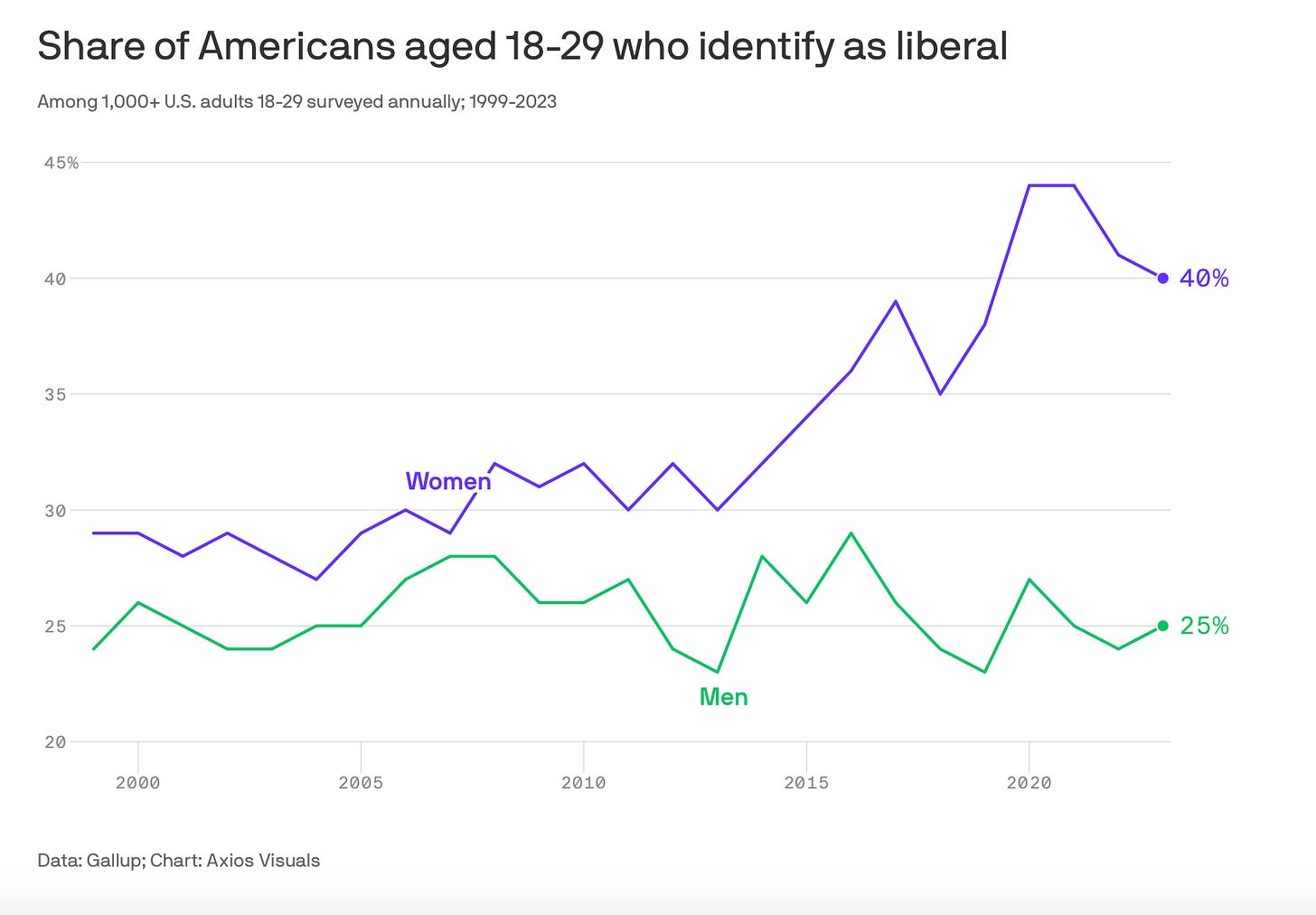

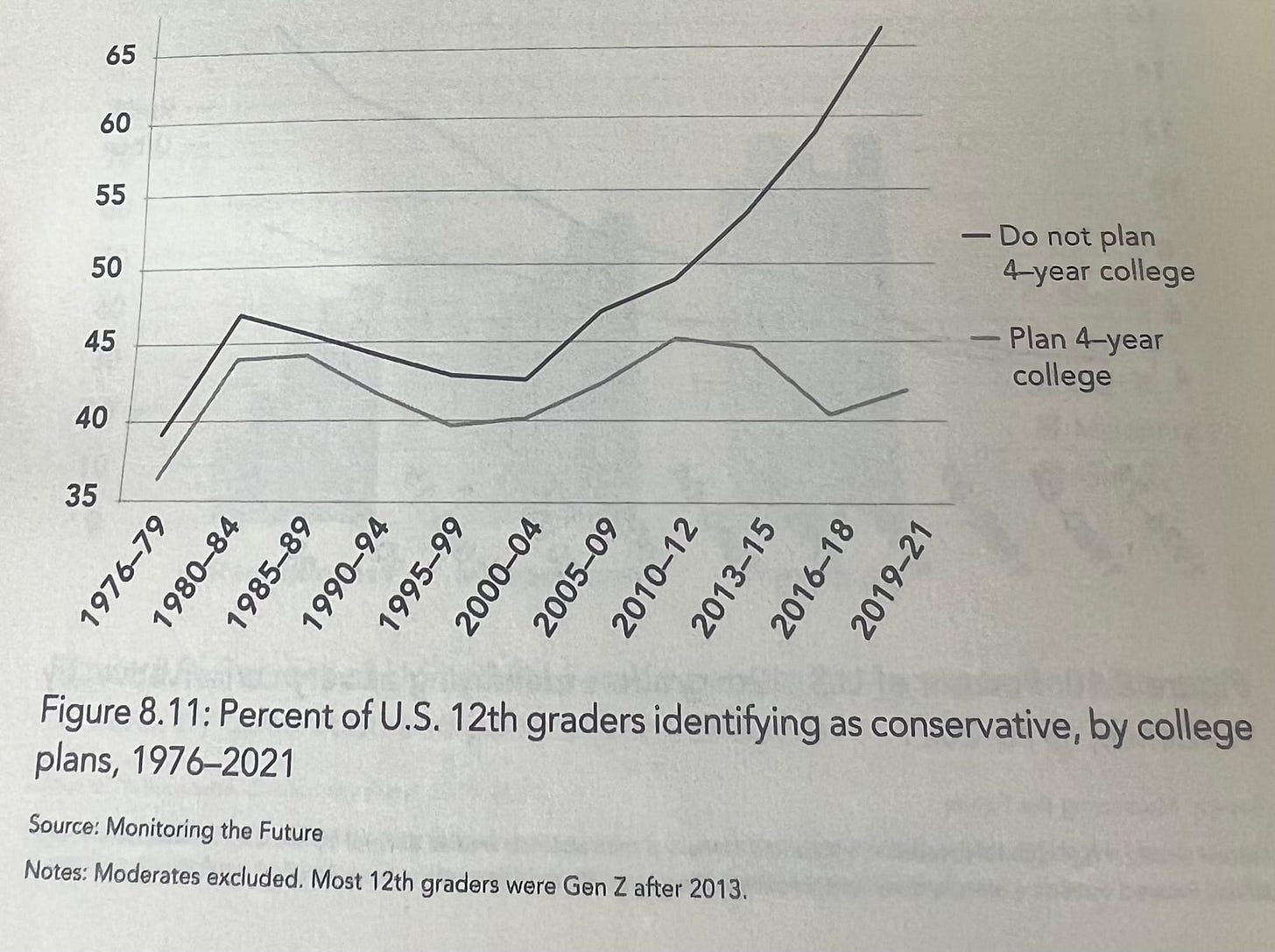

Some things you’ve heard about Gen Z is true. Relative to the rest of the country, they are more progressive than most Americans (41% of Gen Z are liberal or lean liberal per Harvard vs. 25% of all Americans per Gallup). But, within the generation, liberals don’t boast anything close to a supermajority: 29% of the generation describes itself as conservative; 28% describe themselves as moderates.

That also doesn’t make Gen Z much different than previous generations of young people, who were similarly liberal-leaning at our age; if anything, Gen Z is slightly more conservative than prior youngsters. “One-third of Gen Z Americans described themselves as conservative, according to NORC’s 2022 General Social Survey,” the Wall Street Journal recently reported. “That is a larger share identifying as conservative than when millennials, Gen X and baby boomers took the survey when they were the same age, though some of the differences were small and within the survey’s margin of error.”

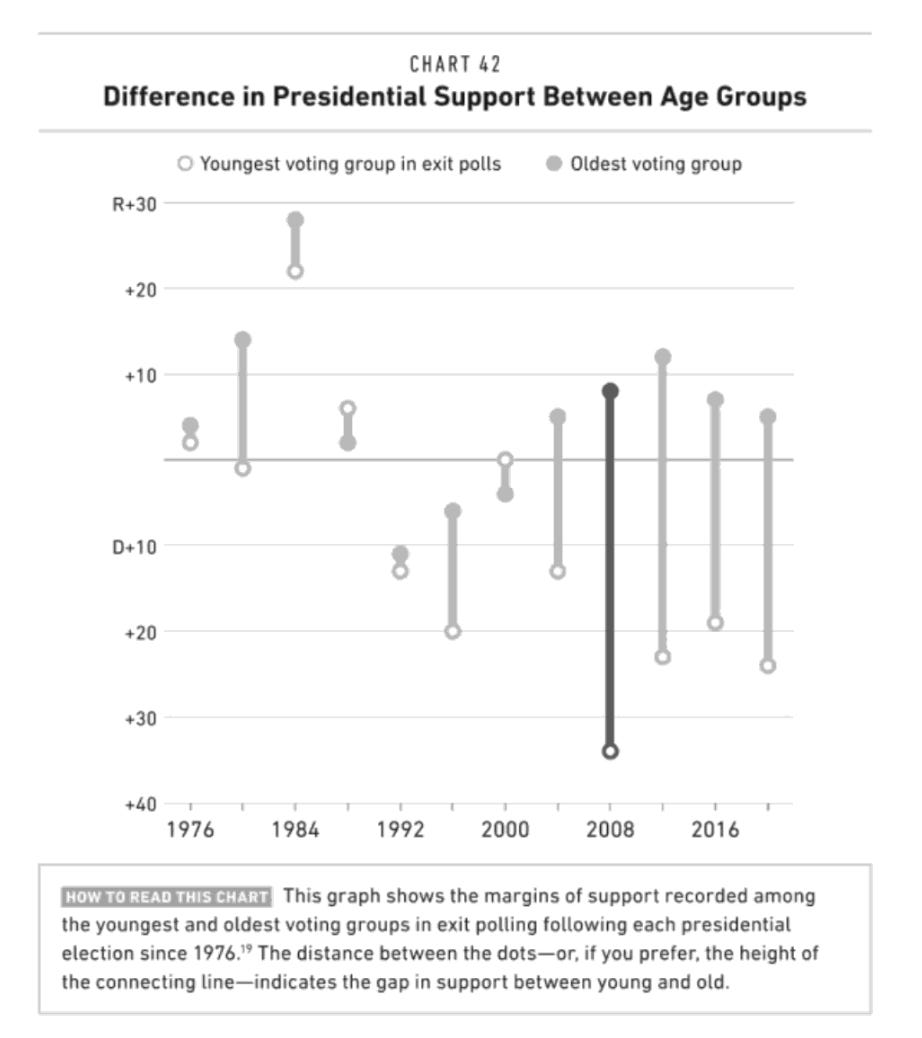

(Notably, liberalism and voting for Democratic candidates are not equivalent. While young voters have historically leaned more liberal, there wasn’t much of a generational gap in voting preferences until 2008, when young voters began surging towards the Democrats. If 2024 polls are true, that large age gap may have been more of a brief exception than a new normal.)

If Gen Z is not more or less politically engaged than other generations, and cares about similar issues as other generations, and is about as liberal as prior generations were at our age — what are the ways we are unique as a cohort? Here are a few:

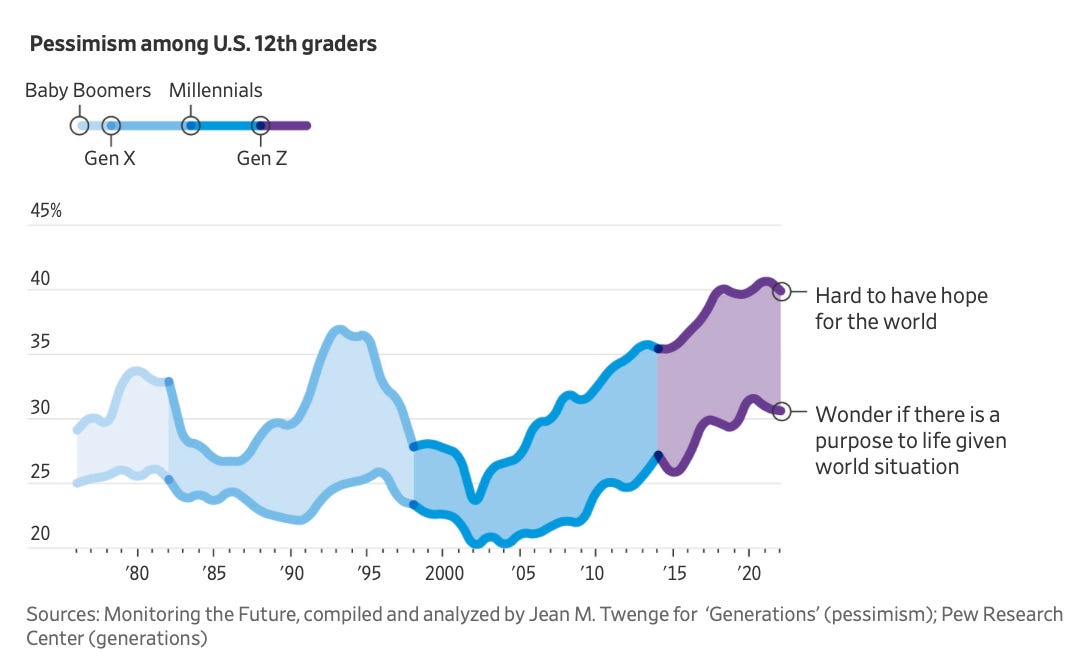

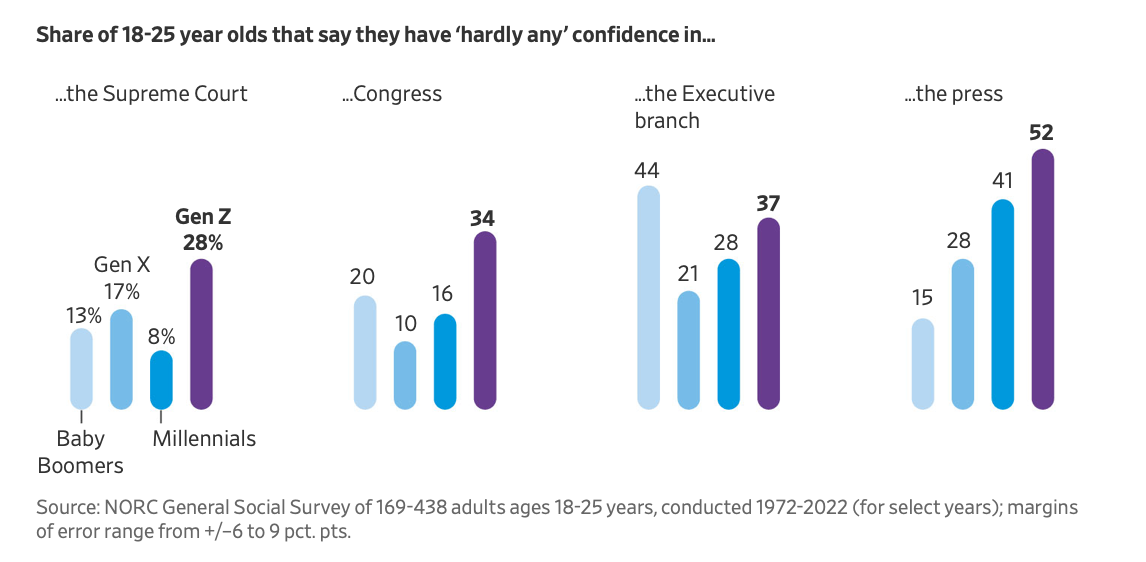

Gen Z is deeply disillusioned and skeptical of institutions. For me, that is the biggest message that courses through all the data among young voters, which shows up whether you look at Gen Z disapproval towards Joe Biden (a creature of the political system), Gen Z support for RFK Jr. (the ultimate disrupter), and the large number of Gen Z voters who refuse to identify with any political party. Other generations are disillusioned right now too, but no one as much as Gen Z and no generation was this disillusioned this young. This frustration with the political system (and the world) is the most salient fact about Gen Z political engagement, above and beyond any specific ideology or political affiliation.

Gen Z grew up immersed in smartphones and social media. The political implications of this are hard to track, but personally, I suspect (and data suggests) it is heavily connected with the aforementioned pessimism — on a personal and societal level. Many scholars believe that technology has helped make Gen Z so much more depressed than previous generations — and it’s hard to separate Gen Z’s worrying level of personal mental health from their political disillusionment with systems and institutions. We are the Doomscrolling Generation.

Gen Z is the most diverse generation in American history, which has seemed to color our social views on race and gender. However, as I wrote earlier this month, it will be a mistake for Democrats to assume that increasing racial diversity is automatically correlated with support for Democratic candidates. Many polls show Biden struggling with young voters of color.

Gen Z is more polarized by education and gender than previous generations were when they were young. Until Gen Z, young people who went to college and those who didn’t were about as likely to be conservative. Not so any more. That means if you’re reading a news article about Gen Z that only encompasses college student voices, you’re not hearing from about 40% of the generation — a 40% that thinks substantially differently from the rest of the cohort. Similarly, young men and women have historically shared similar political views; now, young women are much more likely than young men to be liberal. That means, any time you hear about Gen Z being progressive, you should remember that is largely true of Gen Z women; Gen Z men are trending increasingly conservative.

Many of us have only voted in the age of Trump. What has that wrought? It hasn’t been studied much. Maybe that’s what explains the disillusionment. Maybe that’s what explains the growing gender gap, with men drifting towards Trump and women running away from him. Maybe it has turned young voters off from Republicans — or maybe it has just reframed Gen Z’s idea of what a Republican is. Maybe it means Gen Z views Trump as less of an oddity or aberration, since he has dominated politics for most of our voting lives. More data will need to collected to confirm these theories — but the Trumpiness of our political lives is an important fact to keep in mind when thinking about my generation.

So, yes, Gen Z is unique in certain ways — but not always in the ways that people think, and the picture is much more nuanced than most assume, especially when you take differences by gender, education, and level of political engagement into account.

In other words, media outlets should probably stop highlighting people like me when reporting on Gen Z’s politics. If you’re asking me — a politically engaged and (as of Saturday!) college educated voter — you simply aren’t getting a representative sample of the generation.

Thanks for reading.

I get up each morning to write Wake Up To Politics because I’m committed to offering an independent and reliable news source that helps you navigate our political system and understand what’s going on in government.

The newsletter is completely free and ad-free — but if you appreciate the work that goes into it, here’s how you can help:

Donate to support my work or set up a recurring donation (akin to a regular subscription to another news outlet).

Buy some WUTP merchandise to show off your support (and score a cool mug or hoodie in the process!)

Tell your family, friends, and colleagues to sign up at wakeuptopolitics.com. Every forward helps!

If you have any questions or feedback, feel free to email me: my inbox is always open.

Thanks so much for waking up to politics! Have a great day.

— Gabe