How much do campaigns matter?

They are much better at engagement than persuasion, which is highly relevant for Trump and Biden.

There is an active and long-running debate among political scientists about whether campaigns actually matter.

Especially in an era when the country is so polarized (at least emotionally), how much of an impact do debates, TV ads, and campaign rallies really have on an election? Doesn’t everyone just go back to their partisan corners in the end?

That’s the view of one camp of scholars, who argue that election outcomes are largely pre-determined and barely influenced by campaign machinations. Think American University professor Allan Lichtman and his famous “Keys to the White House,” which take into account broader factors like economic performance and foreign policy events, but not the minutiae of how many doors were knocked on or how many field offices were opened. (Lichtman’s keys have correctly predicted 9 of the last 10 presidential elections, with 2000 as the lone exception.)

Similarly, in an oft-cited 2017 study, professors Joshua Kalla and David Broockman analyzed 49 field experiments that sought to measure how much campaigns influence elections. “The best estimate of the effects of campaign contact and advertising on Americans’ candidates choices in general elections is zero,” they concluded.

Other researchers have come up with different results, of course. A 2023 study by Caroline Le Pennec and Vincent Pons that analyzed elections in 10 countries, including the United States, found that campaigns do play a role in shaping vote choice — but found that the effect in the U.S., while larger than zero, was less than in any of the other nine. (Notably for presidential campaigns, the study also broke down the results in swing states and non-swing states and found that, still, “even in swing states, vote choice formation during the campaign remains lower than in other countries,” but that the effect in swing states is about 50% higher than in non-swing states.)

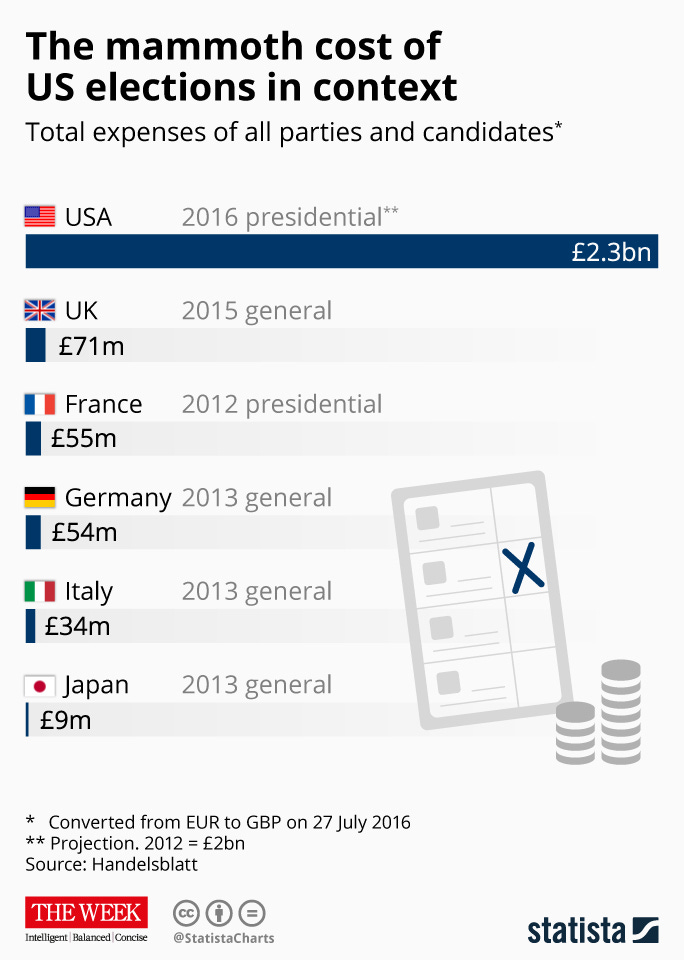

Reviewing the literature, even if you accept that campaigns likely have some effect on vote choice — especially in swing states, where there are larger numbers of undecided voters and where campaigns focus their efforts most intensely — it remains mind-boggling to think of just how much time and money American campaigns plow into activities that only might make a difference.

Not only are American campaigns way, way longer than campaigns in most other countries, they are also much more expensive. That is probably unsurprising to most of you, but you’d no doubt find it very strange if everything you knew about politics came from Le Pennec and Pons, who found that the much-more-costly U.S. campaigns are also, by far, the least effective.

In the 2024 election, a projected $10 billion will be spent on advertising alone, and it might make nary a difference. In a very American fashion, U.S. politicians spend a lot more to achieve a lot less.

But let’s get back to the underlying question. To find an answer, field experiments and event studies — used by the aforementioned political scientists, on both sides of this divide — are all well and good. But perhaps an even better test came in the 2016 election, which was, in the words of Tufts professor Daniel Drezner, “the Mother of All Natural Experiments” for political scientists.

Hillary Clinton outraised Donald Trump two-to-one and hired a campaign staff five times larger than his; she poured money into advertising, field operations, and get-out-the-vote. He, on the other hand, relied largely on earned media and Twitter. We all know how the experiment turned out.

Eight years later, 2024 is shaping up to be another fascinating natural experiment in campaigning’s importance.

This was on my mind recently while reading two different articles about the Biden campaign’s efforts, one in the Washington Post on their outreach to young voters:

Over the summer, [Biden youth outreach director Eve] Levenson and her colleagues plan to focus more on non-students, turning to places young people gather such as bars, sporting events and music festivals like Dreamville Fest in North Carolina, where the campaign canvassed this spring. Online, the campaign is working with influencers and buying digital ads on social media sites such as Snapchat, where it is the top spender of any political campaign.

And the other in the Associated Press on their outreach to older voters:

Nobody stirred, so [Biden campaign volunteer DeAnna] Mireau reached for another scrap. Next was “worker empowerment.” Then “malarkey.” Finally, when she called out “folks,” there was a winner.

“Biden Bingo!” came a quiet voice in the middle of the room. A white-haired man straightened his elbow to raise a triumphant fist in the air. The room filled with applause.

Biden is marrying campaign mainstays like rallies and phone banks with social events like bingo and pickleball to get senior citizens involved in what is likely to be an extremely close election.

The Biden campaign is using time-honored tactics to integrate politics into people’s daily lives in order to engage specific constituencies in the election. It wouldn’t be accurate to say that the Trump campaign isn’t doing any of these kinds of outreach efforts — but they certainly don’t seem to be going very swimmingly.

See this Associated Press piece on recent “Latino Americans for Trump” and “Blacks for Trump” events that featured mostly white attendees. (Trump himself held an event for Black voters this weekend that had a “larger share of Black attendees than is typical of a Trump campaign event,” per the New York Times, although “a significant number of the roughly 200 people in the crowd were white.”) Or see this NOTUS report on a meeting Trump envoy Richard Grenell and Michael Boulos, Trump’s son-in-law, held with Arab-American leaders. (“Frankly, the guy…is clueless on the Middle East,” one attendee said of Grenell.) Or recall that the Trump campaign shuttered most of the RNC’s planned offices aimed at minority outreach and currently has no point person for minority coalitions.

The Trump campaign may be larger and better-funded than its 2016 predecessor, but any operation with Trump at its head will inevitably retain (for better and for worse) a slapdash vibe. So reports the Washington Post:

The [Trump campaign decision to run a “leaner” operation] comes as President Biden’s campaign and its allies, buoyed by incumbency, have been moving in the opposite direction, building a more expansive operation sooner than in 2020. Strategists for both major parties expect Democrats to raise and spend more than Republicans over the coming months, a dynamic that has been magnified by the significant legal costs Trump’s fundraising apparatus has absorbed to defend him in state and federal courts.

The situation has alarmed GOP officials in key states like Arizona, Georgia and Michigan, who have yet to receive promised funding, staff or even briefings on the new plans since the Trump team took control of the Republican National Committee in March. An earlier party blueprint for a general election build-out has been discarded, party officials say. Plans to open new offices have been scuttled. Hiring has been slowed.

Once again, Trump is being dramatically out-spent on advertising (and this was before Biden’s $50 million ad buy announced this morning).

Obviously, Trump’s spontaneity and lack of a professional political operation holds appeal to many voters — who largely disdain professional political operations — so this style arguably cuts both ways for him. But it is striking to me how few resources the Trump campaign seems to be pouring into outreach to some of the aforementioned key communities, despite boasts that he will flip them in November.

Considering the level of dissatisfaction with President Biden among Black, Latino, Arab-American, and young voters, this election presents a rare opportunity for a Republican to make inroads among these communities. There are potential gains on the table for him, gains which could make a big difference in a tight race. And yet, a few recent events notwithstanding, the Trump campaign does not seem to be putting much into these efforts.

Of course, we won’t know until November how this redux of the 2016 experiment will play out. According to polling, though, Biden’s losses do not — so far — seem to be translating into Trump gains. In a new USA TODAY/Suffolk University poll oversampling Black Americans, Biden’s support among Black voters in Pennsylvania has cratered from 92% in 2020 exit polls to 56% today. Trump’s support has barely budged, from 7% in 2020 to 11% today. In Michigan, where 2020 exit polls also showed Black voters splitting 92%-7%, the poll had Black voters now going 54%-15%, reflecting a larger increase for Trump — but still suggesting most of the ex-Biden supporters are looking elsewhere.

Similarly, a recent GenForward poll of young voters — which I discussed at length on NPR — found Biden’s support among voters under 40 dropping from 60% in 2020 to 33% today. Trump’s support, meanwhile, stays exactly constant: 31% then, 31% today.

Biden is hemorrhaging support in key categories, but Trump and his “lean” campaign are struggling to capitalize on it. Of course, that’s not ideal for Biden — in his perfect world, his 2020 supporters would still be supporting him — but it isn’t catastrophic, because he can theoretically make up those losses by increasing his support among older voters (hence the bingo games) and white suburban voters. The defections would be harder to make up if his 2020 supporters were not only not voting for him, but also padding the vote total of the other guy. So far, that isn’t happening.

Then again, perhaps Trump’s less professionalized campaign shouldn’t be blamed for this. Returning to the political science literature on whether — and how — campaigns matter, one consistent finding of many of these studies is that it’s much easier for campaigns to keep voters predisposed towards their party in their fold (Biden’s task) than for their opponents bring them over to a new party (Trump’s task). Consider Ezra Klein’s 2013 summary of a study along these lines:

Campaigns are less successful at persuading undecided voters than they are at encouraging their own partisans to grow more fierce. The manic charges and countercharges of an election mostly remind voters which side they were on to begin with. “Strengthening people’s natural partisan predispositions is one of the most consistent effects of presidential campaigns,” [the study’s authors] Sides and Vavreck wrote. “Democrats or Republicans who at the start of the campaign feel a bit uncertain or unenthusiastic about their party’s nominee will end up dedicated supporters.”

On its face, that’s encouraging news for Biden. Indeed, many of his disillusioned supporters appear to be largely disengaged voters: recent evidence would suggest that, when those voters stay home, Democrats have an upper hand in low-turnout elections made up of highly engaged voters. The political science research further suggests that it will be hard for Trump to coax over the Biden defectors, so many of them will either come home to Biden — or stay home on Election Day. Neither scenario offers much help to Trump (certainly not as much as actually winning those voters over).

In this lens, it makes a bit more sense that Biden’s campaign seems more intent on engaging these voters than Trump’s, since his task is the one campaigns are traditionally much better at accomplishing.

However, when it comes to presidential election analysis, it’s always important to remember that we really only have 59 examples to draw from — a vanishingly small sample size. This XKCD graphic (which even pre-dates 2016, the most obviously unprecedented election) is my favorite reminder that precedents only stand until they’re broken:

In the modern, more polarized era, campaigns generally have had a hard time persuading many of the other side’s traditional constituencies to flip over — and that is surely important to keep in mind when reading polls about Biden’s low support among key groups, and the Trump campaign’s half-hearted efforts to engage them.

On the flip side, in the modern era, it is also uncommon to have this many of a party’s voters this dissatisfied with their nominee this late in the campaign. And to have so many votes who dislike both candidates. Or to have both candidates be one-term presidents. So, while it’s helpful to look at previous examples to predict how Biden’s disaffected voters might act this time, every election is idiosyncratic — this one more than most. It would be foolish to be sure that one more streak could not be broken this November.

Today's Analysis of campaign spending impacts with citation of 2016 Trump's campaign's seeming smaller dollar investment doesn't mention the inordinate much-more-valuable free media attention including the tendency of "fake news sources" like NPR to bend over backwards with questionable equivalencies: comparison of Clinton Foundation with Trump's specious charity, coverage of Clinton e-mail server (exasperated by 11th hour FBI attention). Much like how "fake news sources" gave credence to teaching both Creationism and Darwin at an earlier phase of "culture wars". Sadly, the coverage by organizations like NPR continues to fuel Trump more than Biden. (e.g. the age issue somehow heavily leveraged against slightly older Biden, emphasis on dissatisfaction with amazingly strong USA economy, Biden's trying to bring compromise to Middle East despite its poor prospects for success). Oh, if only FOX were as even handed ...

How much if any change with Rank Choice Voting?