House Quietly Ducks Trump Tariff Vote

Congress forks over more power to the president.

The big news from Congress yesterday was the House passage of a continuing resolution (CR) that would keep the government open through the end of September, staving off a Friday shutdown deadline.

I wrote more here about the bill, which would largely maintain the $1.7 trillion discretionary budget from last year, while increasing defense spending by about $6 billion and decreasing other forms of spending by about $13 billion. The measure passed in a 217-213 vote, with one Democratic supporter (Maine’s Jared Golden) and one Republican dissenter (Kentucky’s Thomas Massie).

The vote was an impressive victory for House Speaker Mike Johnson (R-LA) — many of his conservative members have made a habit of opposing short-term spending bills in the past — and for President Donald Trump, who once again played a key role in the arm-twisting (including by threatening a primary challenge against Massie).

That pretty much places us in a holding pattern: the CR now heads over to the Senate, where it will require support from at least seven Democrats to advance because of the filibuster. Senate Democrats met for two hours yesterday to plot their strategy, but failed to reach a consensus, so we don’t yet know how the vote will shape up. (They’ll meet again today.) Until then, Washington is in wait-and-see mode.

With that pause in the action, I want to turn your attention to a less-noticed — but still consequential — move the House made yesterday regarding the president’s tariffs.

This is going to get a little nerdy, but stay with me: I’m going to explain everything as simply as possible; by the end, I think you’ll see that a move that seems like minute procedure could actually have profound implications. (And possibly even that the people behind the move masked it as complicated procedure precisely so you wouldn’t find out about it. Don’t fall for their trick! If we take it step by step, you’ll be able to understand it.)

OK, let’s dive in.

A key thing to remember to start out is that, before voting on most pieces of legislation that lack supermajority support, the House first has to approve what’s called a “special rule” (but usually just referred to as a “rule”), an adjustment to the chamber’s normal order of business that allows for the vote to take place.

These rule votes are usually (but not always) routine, and the rule resolutions themselves are generally pretty straightforward. On Tuesday, the House approved a rule to allow for consideration of the CR, the first hurdle Republicans had to overcome before they could pass the stopgap spending bill.

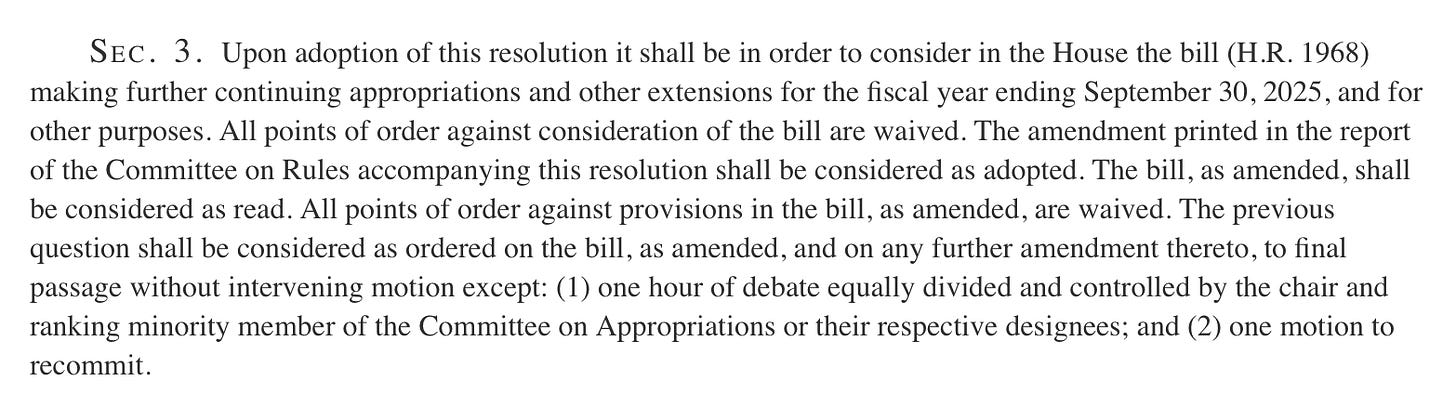

The rule resolution took up four pages total. As always, you can read for yourself, but we’ll walk through the important parts together. Here’s the part that relates to government funding:

Basically, that’s Congress-speak for: the House will debate the CR for one hour and then vote on it. Pretty simple stuff. Sections 1 and 2 of the resolution also authorized similar consideration of two other pieces of legislation.

But then you get to Section 4:

Wait, what? How did national emergencies get into this? And how is a calendar day not a day?

Well, an important thing you should know about the National Emergencies Act is that it’s a key way that Trump has imposed several of his tariffs, including the 20% tariffs on China and the (currently paused) 25% tariffs on Canada and Mexico.

As I noted on Sunday, for those tariffs, Trump has invoked the International Emergency Economic Powers Act, a 1977 law that allows the president to regulate “importation or exportation” if it relates to a national emergency he’s declared under the National Emergencies Act. (Trump has declared a national emergency at the U.S.-Mexico border, which he then expanded to cover the “public health crisis of deaths due to the use of fentanyl and other illicit drugs” flowing in from Canada and China.)

But the National Emergencies Act also gives Congress a way to make sure a president isn’t just declaring national emergencies nilly-willy. Under the latest version of the law, the House and Senate can end a president’s national emergency by both passing a joint resolution — although, importantly, the president can simply veto the resolution. (This is what happened in 2019, when bipartisan majorities voted to end a border emergency Trump declared, but then Trump vetoed the resolution. Two-thirds votes in both chambers are required to override a veto.)

It’s not much, but it’s still something; in this case, it lays out a path for undoing Trump’s tariffs if enough lawmakers opposed them. Without the national emergency that undergirds them, the Canada/China/Mexico tariffs would evaporate.

The framers of the National Emergencies Act understood that a Congress controlled by the president’s party might be loath to hold a vote overturning their co-partisan’s national emergency, which is why the law guarantees that a joint resolution ending an emergency — no matter who introduces it — can get a vote within 18 “calendar days” of its introduction.

Rep. Gregory Meeks (D-NY) introduced a pair of resolutions on March 6 overturning the emergencies baked into Trump’s Canada and Mexico tariff orders. That means the 18-day clock is ticking…or, at least, it was until Tuesday’s rule resolution passed the House. Now that we know the background, let’s return to Section 4 of the rule resolution:

This language essentially means that the House will consider every day until the end of the year to be one long calendar day, at least for the purposes of the process described in the National Emergencies Act. And 18 calendar days can’t pass if you stop counting calendar days! Ergo, the House won’t be forced to vote on the emergency undergirding Trump’s tariffs, as it was on track to be.

Before this rule change, that vote was going to be a fascinating one.

A lot of congressional Republicans have privately expressed concerns about Trump’s tariffs. When forced to put themselves on the record, would any House Republicans object to the politically unpopular tariffs, splitting with the president they adore? With Republicans presiding over such a slim majority, it would only have taken a handful of House defectors for the measure to pass. (And the vote surely would have been played over and over in ads across the 2026 campaign.)

Now, we’ll never know, because of the sleight-of-hand trick executed on Tuesday.

This is a great example of how power slowly migrates from the legislative branch to the executive: the Constitution explicitly gives power over tariffs to Congress. Then, in the 1970s, a Democratic-controlled Congress forked over some of that power to the president, though only during national emergencies that Congress could theoretically terminate.

Now, five decades later, a Republican-controlled House has made it harder to question a president on whether something truly raises to the level of national emergency. You got this, Mr. President, the legislature is saying. We’re not even going to hold a vote on it.

Congress is supposed to be the branch of government where a representative cross-section of the public debates (and votes on) important national issues. Instead, this is yet another turn in the long history of lawmakers excusing themselves from the most controversial — and consequential — discussions of the day, preferring to cede their power to the president rather than take politically risky votes.

As Friend of the Newsletter Kacper Surdy, the procedural maven known as @ringwiss, reminded me over text, it isn’t new for lawmakers to come up with, uh, creative ways to tell time, as they did on Tuesday.

“Congress’ timekeeping has to meet the needs of the day,” he told me, “and each house has exercised its rulemaking power in creative ways to overcome temporal obstacles—going so far as physically turning back the clock in the chamber.”

It’s not uncommon for Congress to declare that a new day is, in fact, a new day for some purposes but not for others. “For example, the House rules provide that during a district work period, a day is not really a day for the purposes of three House rules and one statute,” Surdy said. “It’s funny to read, but it’s really nothing more than a roundabout way of disapplying an inconvenient rule for a certain period of time.”

But Surdy also suggested another possible interpretation of what went down. “The cynical view,” he told me, “is that the purpose of framing it this way is to make it more difficult for those unfamiliar with these procedures to work out what’s being done.”

The House move on Tuesday was wrapped in several layers of procedure: you’d have to know that to pass the CR, the chamber had to pass a rule; then you’d have to find the rule; then you’d have to understand how it prevents a vote being forced under the National Emergencies Act; then you’d have to know that the National Emergencies Act is what allows Trump to impose his tariffs.

By concealing that complexity, House Republicans were able to hide that they’d effectively voted to endorse Trump’s tariffs — one of the more controversial policy questions in Washington right now — or, at the very least, shielded themselves from having to take a stance on them.

Even if they had to tamper with time itself to do it.

People in power often don’t want you to understand these sorts of maneuvers, because it allows them to hide what they’re really doing. But here at Wake Up To Politics, I’m committed to letting you in on the secret: breaking down procedures like this step by step, to make sure you understand how Washington works and why it matters.

If you appreciate that sort of coverage, you can support my work by upgrading to a paid subscription:

@Gabe thanks for the fascinating and horrifying read. Not having heard of this particular House... methodology... before, it seems positively dystopian. Can you elaborate a bit: 1. is there any recourse here? Is the House just allowed to do this because the House gets to modify its rules however it wants, or could the Supreme Court rule that this is illegal? and 2. is this so common that we shouldn't be shocked, or is it (like it reads to me) a surprising case of democratic backsliding?

Thank you for this explanation. Wish we could publish this for ALL to see....and understand!