Foreign Aid Is Unpopular

Adjust your expectations for the USAID fight accordingly.

Democrats have settled on their first real fight of the second Trump administration: defending the fate of the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) against Trump’s efforts to dismantle it.

Progressive members of Congress staged a press conference outside the USAID headquarters on Monday. At one point, the Democrats even tried to enter the building, the most 2017-era “resistance”-like move the party has tried yet. (The lawmakers, like USAID employees, were denied entry.)

At the same time, Democrats also used the foreign aid debate to make their first procedural stand against Trump’s nominees: Sen. Brian Schatz (D-HI) announced that he would slow down confirmations for all of Trump’s State Department picks until “USAID is functional again.” It was a marked change in tone from how Democrats have handled most of the second-term confirmation battles: out of the nine Trump nominees who have received approval so far, only Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth has not received at least some bipartisan support.

Politically speaking, is this a smart fight for Democrats to pick?

To answer that question, it’s useful to start by thinking about why Trump selected USAID — a relatively small agency, charged with distributing humanitarian assistance overseas — as the first arm of the federal government he’s decided to target since returning to office.

Democrats have proposed all sorts of theories. In a thread on X, Sen. Chris Murphy (D-CT) suggested that Trump (and his efficiency czar Elon Musk) are targeting USAID to please China out of concern for their business interests. Other liberal commentators have suggested, without evidence, that Musk holds a grudge against USAID for the role it played in apartheid South Africa.

But Democrats often overthink Trump’s actions, looking for layered conspiracies where none exist. More often than not, the most obvious explanation is the correct one (call it Trump’s Razor), and here the most obvious explanation is that Trump is targeting USAID because 1) foreign aid is not popular, 2) Trump has long disliked it, and 3) he promised voters (especially Gen Z, a key constituency) that he would cut it.

None of this necessarily dictates whether Democrats should be trying to elevate the salience of USAID — there are other reasons besides electoral benefits for doing so, including an altruistic belief that the agency’s work is important and legal concerns about the constitutionality of Trump’s actions — but it does impact whether the party should expect to gain a political boost from doing so.

We’ll start with point #1. Foreign aid is simply not that important to many American voters, and to the extent they think about it, they are generally comfortable with cutting it. A poll during the campaign last year underlined this fact: when YouGov asked voters to select the three foreign policy issues that were most important to them, foreign aid ranked almost at the bottom, chosen by only 18% of voters — including similarly small amounts of both Trump and Harris supporters.

The same poll also found that foreign policy itself is not very important to voters, making foreign aid the thing voters care the second-least about it within the policy area they care the second-least about.

Overall, per YouGov, 59% of voters agreed with Trump’s proposal to “reduce federal spending on foreign aid,” including 82% of Republicans and 39% of Democrats, which is a relatively high showing of Democratic support for a Trump-coded priority.

This reflects a long-standing finding in public opinion that a majority of the country believes the U.S. over-spends on foreign aid. According to a chart by the Gates Foundation’s John Norris — author of a book on USAID — taking an average of high-quality polls for the last six decades, the public turned hard against foreign aid in the Vietnam era. Since then, there has only been one year in which a majority of the country did not believe it should be cut.

Famously, Americans often express a vague desire for spending cuts, which becomes a fierce opposition once you start actually placing programs on the hypothetical chopping block. (Do you want to cut spending? Yes, please! Should we cut Medicare? Social Security? Defense spending? No, of course not!)

A 2013 poll by Pew Research Center found that foreign aid was the lone exception to that rule, the only line item that a plurality of voters (48%) wanted cut. Coming in second place? Funding for the State Department.

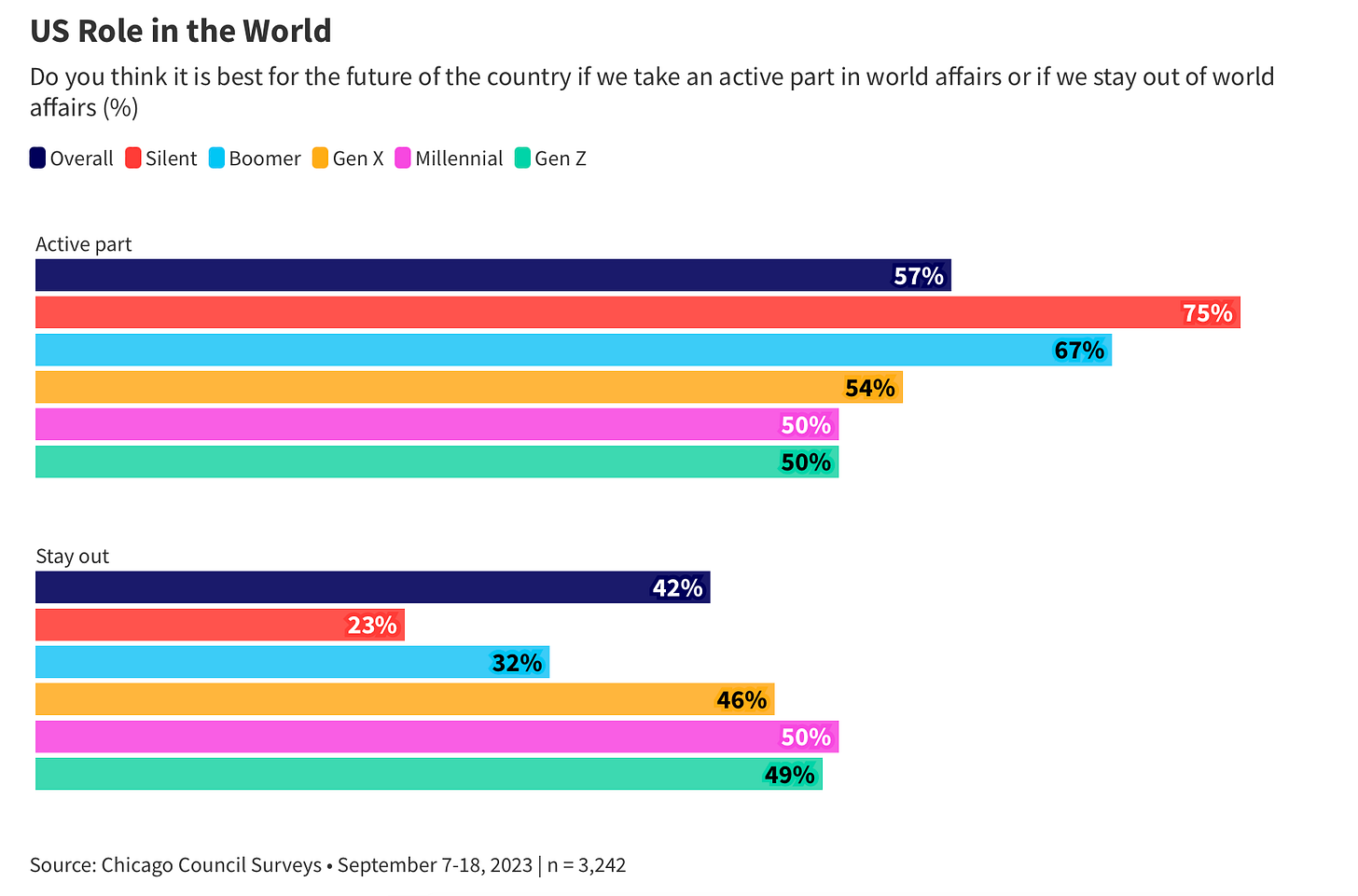

And that was even before the public began turning against the idea of the U.S. taking an “active part in world affairs,” as documented in polling conducted by the Chicago Council on Global Affairs. In the Trump era, the two parties have moved in opposite directions on this question, with the public overall landing last year at 56% in favor of an active role — still a majority, but a noticeable downward trend. Crucially, opinions among Independents have followed Republicans on this question (47% of both groups support an active role), not Democrats (68% want an active role).

Notably, Donald Trump himself has long been a vocal member of the anti-foreign aid majority. Asked about Afghanistan during a 2011 interview with Bill O’Reilly, Trump responded:

With Afghanistan, I want to build our country. You know in Afghanistan, they build a road. At the end of this beautiful road, they build a school. They blow up the school; they blow up the road; we then start all over again. And in New Orleans and in Alabama, we can’t build schools. I want to rebuild the United States.

Three years later, Trump used the prospect of extraterrestrial life to joke about how the U.S. spends too much on other countries (or, in this case, planets):

Put in this light, Trump’s attempts to cut foreign aid as president appear less as an attempt to curry favor with Vladimir Putin and Xi Jinping (as Chris Murphy suggested) and more as the fulfillment of a years-long stance. In fact, isolationist (or or, perhaps, sovereigntist) beliefs — including opposition to immigration, trade deals, and foreign aid — are really the only strongly held views that Trump has had consistently had since before entering politics. Perhaps not surprisingly, those are also the three areas in which he has been most active since returning for his second, no-guardrails term.

Finally, we arrive at the part of this debate that I think has been the most under-covered: not only has Trump long wanted to cut foreign aid, not only does the public agree with him, and not only did they support his promise to do so during the campaign — but the promise was made, repeatedly, to a very specific group for a very specific reason.

There has been a lot of attention paid to the role played by podcasters like Joe Rogan, Theo Von, the Nelk Boys, and others in helping Trump gain support among Gen Z men. Oddly, there has been less attention devoted to what Trump and the hosts actually said on those podcasts that helped him win over so many of their listeners, and ultimately, Gen Z men as a whole.

The answer, to a surprising degree — considering it is not an issue that voters generally, or young voters specifically, have usually cared much about — revolves around foreign policy.

According to a Bloomberg analysis of the nine top podcasters in this genre, the most frequently mentioned political topic on their shows leading up to Election Day was “voting and elections” (things like urging listeners to vote and discussing voter fraud), mentioned on 37% of the episodes Bloomberg reviewed.

Coming in second place? “War,” mentioned in 33% of the episodes. The podcasters, “who tended to be anti-war and isolationist, discussed geopolitics and global conflict, including pontificating about the Russia-Ukraine and Israel-Hamas wars,” Bloomberg explained. “They also speculated about foreign adversaries, including North Korea and China.”

“In eight out of nine shows, hosts and guests painted Trump as a peacekeeper, pushing the idea that there were no wars when he was serving as U.S. president.”

Trump’s brand of isolationism — including his desire to pull the U.S. back from its military and financial entanglements with other countries — was a key selling point to Gen Z. A nice example is this clip of Rogan and Von (the second- and third-most popular podcasters on the Spotify charts) from the week of the election. You can watch below, but I’ll quote them here:

ROGAN: There’s a level of poverty that exists in this country that’s unmanageable. You should never be that poor if you’re part of a community. If you’re a part of a community that takes care of everybody, there’s no reason why you have $175 billion to ship to Ukraine but you don’t have any money to make sure that no one exists below a certain level of poverty in this country.

VON: Yeah, get fucked when that kind of shit happens. They shouldn’t be helping these other countries. I don’t know why we send money to Israel, Ukraine. I just don’t understand — there’s just people suffering here, you know? There’s people that have been taken advantage of in our own country. And it’s like, you don’t want to be selfish but if you don’t know your inventory, then your business is gonna fail, right? That is a law. If you don’t stake stock of your own inveotory, your business will fail. And we don’t have stock of our own inventory. And we don’t have a healthy inventory.

This is the exact argument that Trump has been making in recent days: that the money the U.S. gives to other countries would be better spent on citizens here at home. It is an argument that has long boasted public support — but has specifically resonated with younger voters.

Anecdotally, I hear it all the time from Gen Z friends across the political spectrum. And the same isolationist streak is evident in polling data as well. The aforementioned Chicago Council on Global Affairs poll on whether the U.S. should have an active role in the world shows a clear generational divide:

To take the most controversial recent example, a Monmouth University poll on last year’s Israel/Ukraine/Taiwan foreign aid package similarly found that 18-to-34-year-olds were the only age group opposed, while older Americans (like lawmakers in Washington) were supportive of the package.

Again, none of this means Democrats should or shouldn’t be waging a fight over USAID. It’s possible for the politics, law, and morality of a public policy question to point in different directions — but it’s also important to analyze each prong individually, without being biased by your opinions on the other two.

In this case, polling suggests that Trump has more to gain from making USAID salient than Democrats — especially with young voters, a group among whom Democrats are already struggling to gain traction.

Some commentators have suggested that Democrats would be smarter not to make this a fight about foreign aid itself, but rather about the dubious legality of Trump’s actions. I’m not so sure that would be politically advantageous either.

As I’ve written previously, voters historically don’t get too bothered about abuses of executive power. Again, young voters are a particularly group to watch here: according to a recent poll by More in Common, when asked if Trump should try to “get things done, even it means sometimes ignoring the Constitution,” 42% of Gen Z men — more than any demographic — answered in the affirmative.

Of course, there is also the very good chance that Trump overreaches and moves public opinion against him. As a rule, American voters are not averse to cutting foreign aid — but that could change as more sympathetic stories emerge about what it would really mean for USAID to disappear.

Already, “at a minimum, 300 babies that wouldn’t have had HIV, now do,” because of the foreign aid pause, one USAID worker told Wired. We could end up in the situation that so frustrated Josh Lyman in “The West Wing”: a large segment of the country thinking that the U.S. gives too much in foreign aid, while simultaneously objecting to it being cut.

This fight poses dangers for both sides of the aisle — but, as always, it’s important to go into the debate aware of which party holds a public opinion advantage at the outset, which (if the parties are smart) should shape how they opt to frame their messaging and how salient they choose to make it.

In this case, decades of public polling align to suggest that Trump has public opinion on his side on foreign aid, especially among the rising generation of American voters. At least, he does for now.

More news to know

Tariffs against Canada and Mexico have been paused for one month after the two countries made (mostly recycled) pledges on border enforcement, while the increased 10% tariffs against China went into effect this morning. Beijing responded with tariffs on American coal and natural gas, plus an investigation into Google.

Robert F. Kennedy Jr. and Tulsi Gabbard both appear set to receive Senate confirmation. Kennedy’s nomination was approved by the Senate Finance Committee this morning, with the critical support of Sen. Bill Cassidy (R-LA); later today, Gabbard is set to be approved by the Senate Intelligence Committee, after Sens. Susan Collins (R-ME) and Todd Young (R-IN) signaled their support.

Democrats plan to introduce legislation to revoke Elon Musk’s access to the Treasury Department’s payment systems. The New York Times has reported that Musk’s team has read-only access to the systems, while Wired has reported that his deputies can, in fact, make changes. Two federal employees unions have already sued, alleging that the Musk team’s access is a privacy violation.

U.S. District Judge Loren AliKhan, the Biden appointee who last week blocked Trump’s federal funding freeze, extended the order on Monday, accusing the White House of being “disingenuous” by claiming to have ended the freeze while still carrying it out in practice.

More headlines:

Axios: 20,000 federal workers take “buyout” so far, official says

NBC: Some migrants arrested in Trump's immigration crackdown have been released back into the U.S.

CNBC: Trump signs order establishing a sovereign wealth fund that he says could buy TikTok

The day ahead

President Donald Trump will meet with Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, the first foreign leader he’s hosted at the White House since returning to office. Trump will also hold a joint press conference with Netanyahu and sign executive orders withdrawing the U.S. from the United Nations Human Rights Council and prohibiting funding for the UN relief agency in Gaza.

The Senate will vote on confirmation of former Rep. Doug Collins (R-GA) to be Secretary of Veterans Affairs.

The House will vote on up to six pieces of legislation.

The Supreme Court has no oral arguments this week.

This is so fascinating and confusing to me. The theory that cutting foreign aid appeals to anti-war isolationists especially -- I'm not honestly convinced that those two things are related, but maybe that's because I don't see the connection between funding global anti-poverty and public health and funding weapons development. Like, if the goal is to appeal to anti-war folks, why aren't we cutting defense spending?

I'm also curious if anyone knows of any more recent polling on American civic knowledge about budget breakdown. I know polls in the past have shown that Americans as a whole drastically overestimate the percentage of the federal budget that actually goes to foreign aid but the most recent one I found is from 2015 (https://www.kff.org/global-health-policy/poll-finding/americans-views-on-the-u-s-role-in-global-health/). But at that time Americans on average apparently believed that we spent more than 30% of our budget on foreign aid, and 15% of Americans believed we spent more than half! So I also feel like cutting foreign aid could very easily be a way for the Trump admin to make it seem like they are making huge cuts in spending, which is popular, while actually making almost no difference to the federal bottom line (and coincidentally depriving humanitarian aid-workers, who are not likely Trump voters, of their income and livelihoods).

Oh, Gabe. I am so disappointed.

An unelected individual is overriding congressionally mandated spending, essentially staging a coup, and you decided to focus today's post on why Trump thinks killing USAID is a good idea?