Does Anybody Believe Anything?

Ideology rarely survives contact with governance.

I.

Imagine, for a moment, that Kamala Harris won the presidency in 2024. Democrats sweep into power with narrow majorities in the House and Senate. Having promised during the campaign to codify Roe v. Wade into law, she briefly tries to convince Congress to carry out that goal. But some Senate Democrats get cold feet about eliminating the filibuster. No legislative progress on abortion appears likely.

So, instead, Harris decides to deploy her executive power. She uses federal land, like national parks, to set up abortion clinics in red states.

Anti-abortion protests quickly spring up outside the new clinics. Yellowstone National Park becomes a flashpoint. Pro-life activists in Wyoming rally against the Harris administration, supported by the state’s Republican governor.

The National Park Service’s law enforcement rangers are rushed to the area. Confrontations with protesters turn tense. Public opinion begins to sour: while directionally in favor of abortion rights, voters grow uneasy with the aggressive use of executive power and the assault on federalism. One snowy morning, as protesters assume their normal place (legally) videoing people as they enter the abortion clinic, a park police officer pushes one woman away. Another right-wing activist, armed with a gun, goes to help her. The federal officers, stretched to their limits and unused to dealing with such situations so far from their normal jurisdiction, restrain him and shoot him in the scuffle. The man dies.

Is there any doubt, in the hypothetical I just described, that Republicans would be apoplectic about the shooting, or that Democrats would be inclined to give the federal officer the benefit of the doubt?

The slain activist would be called a patriot on the right, and a gun-toting nut on the left. He shouldn’t have stormed towards law enforcement with a weapon, Democrats would say. Our Second Amendment rights are under attack, Republicans would retort.

Hypocrisy, thy name is politician.

If recent statements from Democratic and Republican politicians are to be believed, the U.S. has undergone a striking realignment on the Second Amendment over the last week.

“I don’t know of any peaceful protester that shows up with a gun and ammunition rather than a sign,” Homeland Security Secretary Kristi Noem said on Saturday, hours after Alex Pretti was killed by Border Patrol agents in Minneapolis while possessing a concealed firearm, which he was licensed to carry. “You cannot bring a firearm loaded with multiple magazines to any sort of protest that you want,” FBI Director Kash Patel echoed, despite the fact that Republicans (Noem and Patel included) have spent years defending armed protesters like Kyle Rittenhouse and the January 6th rioters trying to do just that.

Meanwhile, in response to President Trump saying that “you can’t walk in” —presumably, to a protest — “with guns,” Gov. Gavin Newsom (D-CA) posted that “Donald Trump does not support the 2nd Amendment.” But Newsom himself signed a law in 2023 that banned concealed carry at permitted public demonstrations, which would seem to suggest by his own logic that he does not support the amendment either. Shouldn’t he be celebrating the fact that Trump has joined him in his stance? Meanwhile, an official X account of the Democratic Party posted a message quoting, of all people, Glenn Beck saying that Americans have a “constitutionally protected” right to “carry a gun at a protest,” despite the fact that most Democratic-controlled states ban exactly that.

Should we be surprised that leaders of both political parties managed to so easily shift their rhetoric on a supposedly core belief? Well, that depends how we think about the process of political parties forming their ideologies.

II.

In their 2023 book, “The Myth of Left and Right,” the political scientists (and brothers) Verlan and Hyrum Lewis argue that there are two ways to think about the left-right divide.

First, there is the traditional way, which they call the “essentialist theory of ideology.” This is the belief that there is some philosophical essence that unites the American left (both connecting its current adherents, and connecting its present incarnation to its predecessors) and another that unites the American right. There is some “master issue” — be it big government vs. small government, or change vs. preservation, or something else — that divides the two sides, and you can order people according to their opinions on that question, and that’s what creates the left-right spectrum.

People who take the “left” side of this big, underlying question will naturally take the “left” side of various other sub-issues, because your answer to the “master issue” informs your answer to the sub-issues, and that’s how parties end up with ideologies.

The Lewis brothers don’t believe in this.

“What’s happening in our politics is people identify with one of our two major political tribes, and then they adopt the issue positions of their tribe as a matter of course,” Verlan Lewis, a professor at Utah Valley University, told me in a recent interview. “So rather than being driven by some [broader ideology], it’s typically socialization. You’re justifying whatever your tribe is up to and criticizing whatever the other tribe is up to.”

“Left-right ideologies are bundles of unrelated political positions connected by nothing other than a group,” the Lewises write. They call this the “social theory of ideology,” and they seek to prove it by showing that on nearly every issue, what has been considered the stance of the “left” and “right” in the U.S. has bounced around the map.

“When the Republican Party moved in a small-government direction under Barry Goldwater, essentialists called it a move ‘to the right,’ but when the Republican Party moved in a big-government direction under George W. Bush and Donald Trump, they also called it a move ‘to the right,’” the Lewises write. “When the Republican Party moved to foreign interventionism under Bush, they said it was a move ‘to the right,’ but when the Republican Party moved to foreign isolationism under Trump, they also said it was a move “to the right.’”

As the party leaders move, often so do the voters: the Lewises point to studies showing people will often shelve their beliefs once they’re told their party feels differently, showing that belief systems are often more socially than ideologically constructed.

In this thinking, there is no philosophical strand that ties together all the positions of the modern-day “right” or “left,” or connects those positions to what has previously been called “right” or “left.” Instead, the Lewises write, Republican voters adopt the positions of Republican politicians and Democratic voters adopt the positions of Democratic politicians, and we call something right-wing when the Republicans do it, and left-wing when the Democrats do. And then, at every stage, we construct after-the-fact philosophical rationalizations that purport to tie these “ideologies” together, when really they are disconnected baskets of ideas that are stitched together at the top, out of convenience and not principle.

What really connects one’s stance on immigration to their position on guns, anyway? Nothing, Lewis says, which is why you see the parties easily shedding one of them to defend the other. “The issue positions of our two major tribes are constantly evolving, and right now we’re seeing a test of this because of what happened in Minneapolis,” Lewis told me.

“Is [Pretti] a patriotic gun owner exercising his Second Amendment rights, which codes conservative in our political parlance? Or is he an anti-ICE enforcement protester, which codes progressive or left-wing in our politics?” Lewis continues. Each party is picking selectively according to what is needed in the moment, just as they surely would in my Yellowstone/abortion hypothetical.

“So because people just want to justify what their group does or criticize what the other group does, they end up changing their own issue conditions to go along with that,” Lewis said.

III.

Does this mean that the NRA is about to become a Democratic interest group, or that Republicans will soon be the anti-gun party?

Not so fast. But it does beg the question of how political parties end up modifying their ideologies in a long-term way. We’ve established that it’s possible to do so (and that most members of a group will follow their social peers), but that doesn’t tell us the mechanism of when it can take place.

As it happens, this is the topic of another book by Verlan Lewis, “Ideas of Power.” In that book, Lewis argues that the mechanism actually has a lot to do with the type of pattern we’re seeing now: party ideologies often wither upon making contact with wielding governmental power.

The basic pattern goes like this: you have a small-government party and a big-government party. The big-government party is in power. The small-government party argues that the government must be smaller. Then, the small-government party wins power. Suddenly, it is the government, and it starts to feel better about the size of government. (Weird!) In turn, the former big-government party (now that they are not the government) starts to grow skeptical of government. The small-government party moves more in a big-government direction and vice versa. And then, the cycle starts itself over again.

Lewis chronicles a litany of examples in his book of parties criticizing governmental intervention in the economy and foreign policy — right up until they become the government. Here are two. On the campaign trail in 1932, Franklin Roosevelt accused his rival Herbert Hoover of being “committed to the idea that we ought to center control of everything in Washington as rapidly as possible.” Noting that “our Federal Government has experienced unprecedented deficits,” he said that he considered “reduction in Federal spending” to be “one of the most important issues of this campaign.” It is “the most direct and effective contribution that Government can make to business,” he explained.

Similarly, in 2000, George W. Bush said at a debate that he was “worried about over-committing our military around the world.” He bashed Al Gore for not being “judicious in its use,” particularly the Clinton administration’s intervention in Haiti as not a “worthwhile” mission because “it was a nation-building mission.” Bush said: “It cost us a couple billions of dollars and I’m not sure democracy is any better off in Haiti than it was before.”

We know what happened both times. Once they actually held the reins of power, the two parties realized they weren’t so averse to the exact types of governmental power they once criticized. And then American politics re-oriented itself around these realities, with the out-parties in both cases growing more averse to governmental interventions in, respectively, the economy and foreign policy.

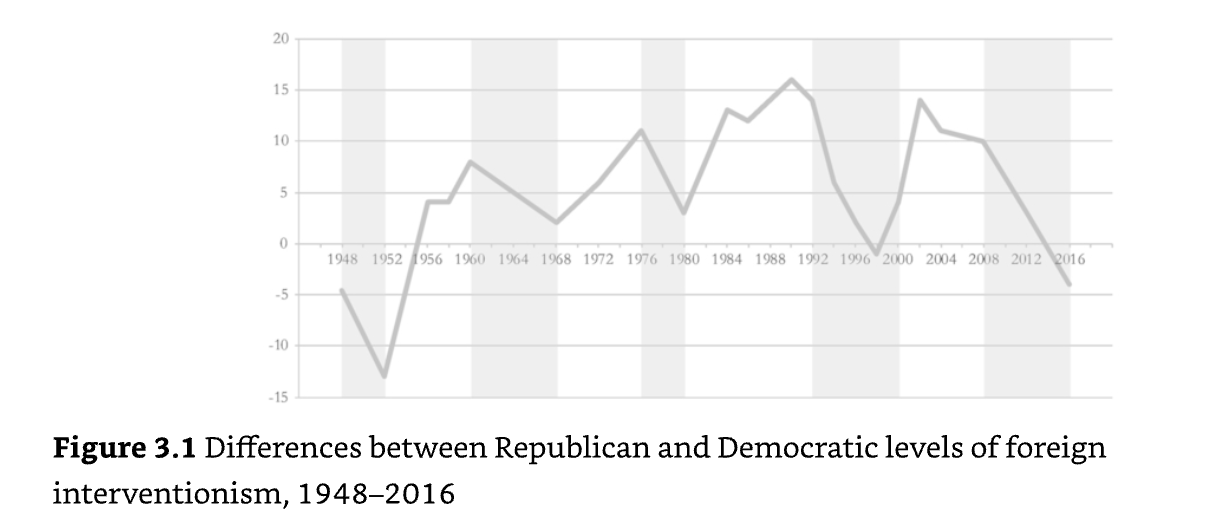

The below graph charts the difference between Republican and Democratic levels of support for foreign interventionism according to a long-running survey. The line moving higher means that Republicans were more supportive of foreign interventionism than Democrats. The shaded areas are when a Democrat was in the White House. Inevitably, each time, the gap narrows during Democratic administrations — meaning Democrats became more favorable to (their party conducting) foreign intervention, while Republicans became less favorable — and then widens during periods of Republican control.

A new poll from Politico finding that Trump voters (isolationist as recently as the Biden era) now overwhelmingly support military action abroad shows this pattern repeating again; there are also charts showing the same dynamic on other issues, such as each party expressing increased concern about fiscal responsibility just as soon as they leave office.

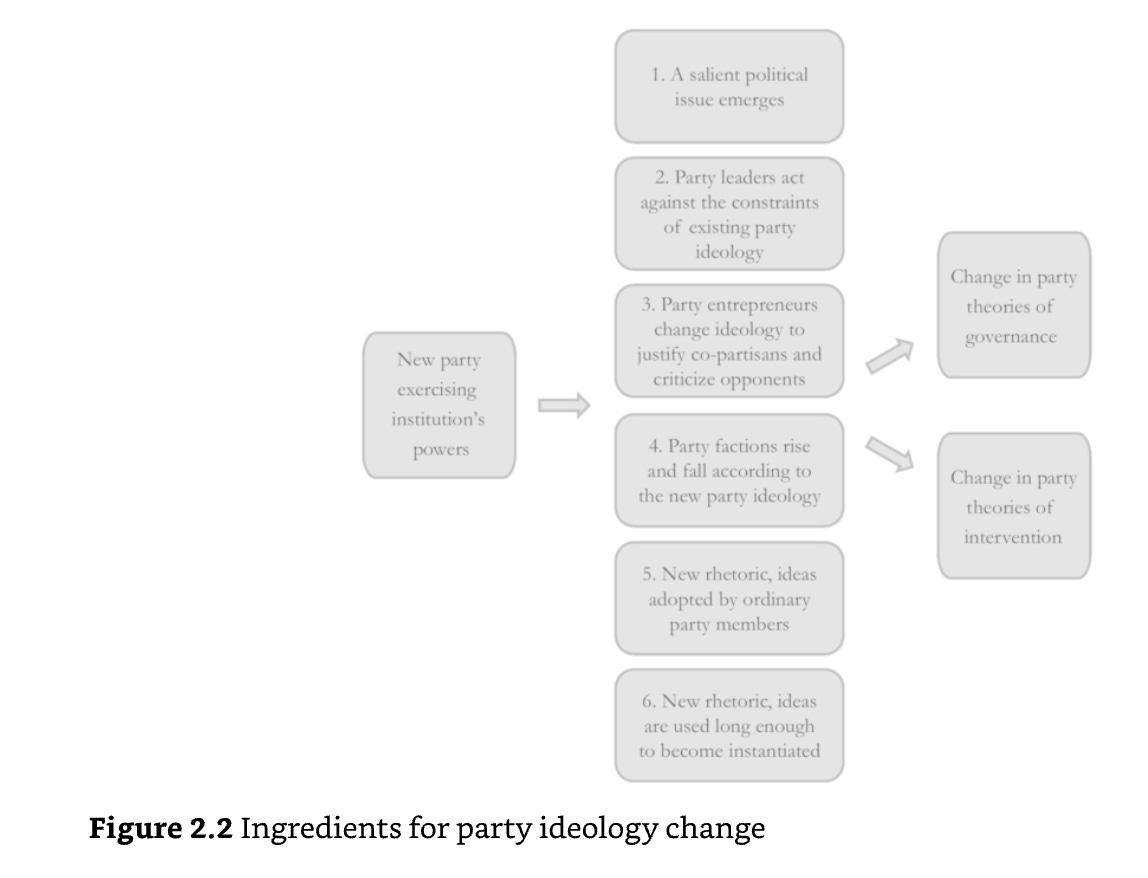

A lasting realignment isn’t easy to pull off, however. According to Lewis, it involves six steps:

Something happens in the world that causes the governing party to shift its principles.

The party’s leaders have to be “willing to act in ways contrary to the party’s previous ideological commitments.”

“Party entrepreneurs” — members of Congress, activists — have to then embrace the shift.

A corresponding shift has to take place among the party’s allied interest groups, with groups favoring the new outlook rising and groups favoring the old outlook on the wane.

Rank-and-file voters have to accept the change.

The new language has to be used long enough that it cements itself as party orthodoxy.

From this formulation, we can be fairly confident that a lasting realignment on guns is probably not forthcoming. At least on the Republican side, Steps 1 and 2 are clearly present: a catalyzing event and party leaders (Trump, Noem, Patel) willing to shed party commitments in favor of the needs of the moment.

Step 3 — the opinions of the “party entrepreneurs” — is an active battleground. Obviously, Trump administration officials have come down on the side less committed to gun rights, as have Fox News hosts like Will Cain and Jesse Watters. Ditto Sen. Tommy Tuberville (R-AL) who said this week, “Why would you take a gun? I don’t understand that. I don’t understand that. Law enforcement carries guns. And you know, you take a gun, nothing good can happen.”

Many Republican lawmakers, though, have taken the opposite tack, with senators like Majority Leader John Thune (R-SD), Mike Crapo (R-ID), and Ted Budd (R-NC), among others, reaffirming (in Budd’s words) that “Americans have a constitutional right to bear arms, and the mere possession of a firearm does not represent a threat justifying lethal force.”

Step 4 essentially pits the anti-immigration faction in the GOP against the pro-gun faction, and sees which one is stronger. So far, it seems like the reigning administration is favoring the former, but the gun rights faction is much more entrenched and organized within the broader party. Groups like the NRA and Gun Owners of America are certainly not giving up without a fight: “The NRA unequivocally believes that all law-abiding citizens have a right to keep and bear arms anywhere they have a legal right to be,” the organization wrote this week on X.

Step 5 (on where the voter base is) would require polling we haven’t yet seen, though I’d be fascinated to see surveys asking pro-Second Amendment Republican voters what they make of Pretti’s rights in this situation.

And, finally, Step 5 simply requires time, when — in all likelihood — the party will move on and revert to its usual position by the time the next controversy rolls along.

It is also unlikely a full transformation will take place on the other side: Newsom and others are using their rhetoric opportunistically, but probably not in a lasting way. Then again, you start seeing some interesting tensions emerging here as well, as you see the out-of-government party experimenting with a historically anti-government position (gun rights) that may not line up with its ideological commitments but does match up with its status in the governmental structure.

“For years I quietly mocked 2A defenders who argued arms were necessary to defend American rights against a tyrannical government,” former Rep. Dean Phillips (D-MN) wrote on X. “Today I apologize, because I’ve seen it with my own eyes.” Video of a self-identified liberal saying that he just bought his first AR-15 (“The Second Amendment is for all of us”) has gone viral on Instagram. Will this translate to a broader change in the partisan composition of gun ownership? Per an NPR story earlier this month, groups of progressive gun owners are seeing unprecedented surges in membership.

IV.

If anything, though, these partial transformations can be even more revealing, showing us out in the open how hollow the two parties’ “bundles” of issue positions can be, and the divides that can break out when party leaders start picking and choosing among the bundle according to the needs of the moment (and their status in Washington).

It also speaks to the patterns Lewis writes about in “Ideas of Power,” on the inherent tension in a small-government party — here, the Republicans — becoming the government.

In some ways, Donald Trump is Lewis’ theories in flesh: both someone as ideologically flexible as any president in recent memory (“The Myth of Left and Right” personified) and a crusading government outsider whose positions have suddenly shifted once he was placed in Washington (see “Ideas of Power”).

We’ve seen the results all year, from Trump exploding the deficit to his turn from railing against government censorship and political prosecutions to embracing them; from his move from isolationism to interventionism (Lewis predicts that a party out of power will inevitably call for a smaller military, while a party in power will do the opposite) to his move away from GOP orthodoxies on state’s rights.

At each stage, it has been interesting to see where party “entrepreneurs” and voters have thrown up roadblocks and where they haven’t. Few complaints were aired about the deficit-busting One Big Beautiful Bill or National Guard deployments into states. But Trump’s ability to trample over GOP orthodoxy is not complete, as the response to two separate shootings show: his move towards censorship after Charlie Kirk’s assassination was stopped by Republican lawmakers, who have similarly drawn a line at his pivot on gun rights.

As parties shift their emphases, voters will often shift their allegiances in response. One dimension of this I’m interested in is the libertarian faction within the GOP: recall that Donald Trump spoke at the Libertarian National Convention in 2024, and the party’s leaders repeatedly praised Trump at the expense of their own nominee. Perhaps as a result, the Libertarian candidate performed markedly worse in 2024 (drawing 0.4% of the vote) than in 2016 (3.3%) or 2020 (1.2%) — enough of a shift to matter in a close race.

Since then, many of the most libertarian-leaning members of Congress, including Rep. Thomas Massie (R-KY) and Sen. Rand Paul (R-KY), have broken with Trump over his decidedly un-libertarian-like positions on tariffs, gun rights, and other issues. It will be interesting to see where this faction (which includes many young men, a critical demographic) swings in 2026. This week, the Libertarian Party’s chair came out in support of abolishing ICE.

Meanwhile, Lewis’ work would predict concurrent shifts within the Democratic coalition — some of which we’ve seen. Most notably, perhaps, there has been a renaissance of Democratic support for federalism and state’s rights, which is what Lewis would predict now that Democratic power is mostly contained to various state governments: as their power in the federal government has waned, so has their support for federal power.

And Republicans have responded in kind: “ICE > MN,” Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth wrote recently, surely not the sort of language he would have used about an Obama-era federal agency when he was a 2012 Republican Senate candidate in Minnesota.

V.

None of this is squarely about Alex Pretti’s death, or the morality or legality thereof. Rather, it is about the second-order questions of the political rhetoric in its wake: about how Republican and Democratic leaders have subordinated their historical commitments on gun rights and federalism to their needs in the moment, and the degree to which the rest of their parties are or aren’t following.

Above all, Lewis’ work reminds us that each party’s positions — even though they inevitably hold up them as moral necessities at any given time — are fluid. We’ve seen this before, including on guns, which were once an issue without much of a partisan valence.

Gun rights are often promoted as an inherently anti-government position, so it isn’t surprising to see (as Lewis would predict) the tensions that emerge when the small-government party takes power. It’s easy to support one’s rights to bear arms against a potentially overbearing government from the outside. It’s different once you’re the potentially overbearing government.

“We can’t trust our government anymore,” Homeland Security Secretary Kristi Noem told CNN’s Dana Bash last year, perhaps by reflex. “But you are the government,” Bash had to remind her.

Lewis thinks times where we see party leaders opportunistically shifting their rhetoric can serve as helpful moments to take a step back and practice some humility. “Instead of falsely bundling together all these issue positions that don’t necessarily have to go together, let’s just talk about the particular issues, and once we do that, we can also recognize on any given issue, ‘I might be correct and I might be wrong, because I’m not infallible,’” Lewis told me. “I don’t have some infallible philosophy. I want to be guided by certain principles, but how I apply my philosophy, my values, my principles, and everyday life is going to be difficult and complicated, and I might get it right and I might get it wrong, and that’s okay.”

He adds that it’s important to recognize that labels like “Democrat” or “Republican” and “left” or “right” refer to a “social group phenomenon,” not two perfectly coherent moral philosophies where one side is completely right on a big “master issue” (and the attached sub-issues) and the other side is completely wrong, because — in his view — there is no one big, underlying issue.

“We’re just talking about a group of people who agree to act together to try to achieve certain ends, and that’s okay, and that’s fine. That’s politics,” he said. “You have to have parties in politics. There’s nothing wrong with partisanship, per se, it’s just there’s healthy partisanship and there’s unhealthy partisanship. A healthy partisanship says, ‘my party’s correct about some things, they’re wrong about some things’ and the same thing about the other party, and that’s okay. The unhealthy tribal partisanship says my party’s correct about everything, and the other party’s wrong about everything.”

It’s also important to pay attention to which politicians are feeding into which types of partisanship.

It’s been notable to watch those, like Tuberville and Newsom, willing to quickly drop positions they’ve previously held up as moral necessities. On the other hand, there are many Republican lawmakers who have broken with Trump on this issue — as well as someone like Marjorie Taylor Greene, who explored a similar hypothetical to my own to urge MAGA voters to rethink what might have been their reflexive lack of sympathy for Pretti. On the Democratic side, Sen. Chris Murphy (D-CT) laid out the more nuanced view of reiterating his opposition to concealed carry while saying that someone in a state that has that right (like Minnesota) should be able to practice it, showing that it’s possible to defend Pretti’s right to bring a gun to this protest (in accordance with the laws on the books in Minnesota) without pretending (like Newsom) that he views that right as a constitutional moral imperative that he is outraged to see his opponents abandon.

These can be important moments to test yourself, and ask whether your positions are situational or principled. Do you believe the Second Amendment protects the right to bring a gun to a demonstration? Do you believe a protester deserves added suspicion if they are armed? Should law enforcement view them differently? What is the proper arrangement of state and federal power?

Are those your consistent stances, no matter who is protesting or who is in control in a given state or in Washington?

These are separate than many of the more important questions about Pretti’s killing, which speak to acceptable use of force on the part of law enforcement — but, in light of some of the second-order rhetoric floating around, it is good to test yourself, and see whether you are contributing to a healthier, more humble partisanship or whether your principles are easily shelved depending on the reflexive needs of your tribe in a given moment.

Parties’ stances often evolve, but that doesn’t mean yours have to.

Excellent article, Gabe. You nailed the basic problem with our entrenched 2-party system right on the head. It's encouraging to see more and more Americans NOT identifying with either major party. I long for the day when we have a truly dynamic political system, where parties are 100% about ideology, and are constantly forming, dying, merging, and splitting.

I almost didn't read further than the 1st 2 paragraphs because they irritated me with their "false equivalence." The whole set-up for the hypothetical is wrong on so many levels. First, the feds are on federal land, not in our neighborhoods like ICE is. Second, there have been countless instances of douchbaggery by ICE, culminating in the killing of Alex Pretti, but in Gabe's scenario this is a one-off. You missed the mark, Gabe. (I liked the rest of the post tho)