Color-Blind or Anti-Racist: The Supreme Court Mulls the Constitution’s Racial Legacy

Inside the Supreme Court during a consequential hearing.

Let’s get one thing out of the way before discussing the Supreme Court’s oral arguments on the Voting Rights Act yesterday: Yes, the ruling could have a large political impact.

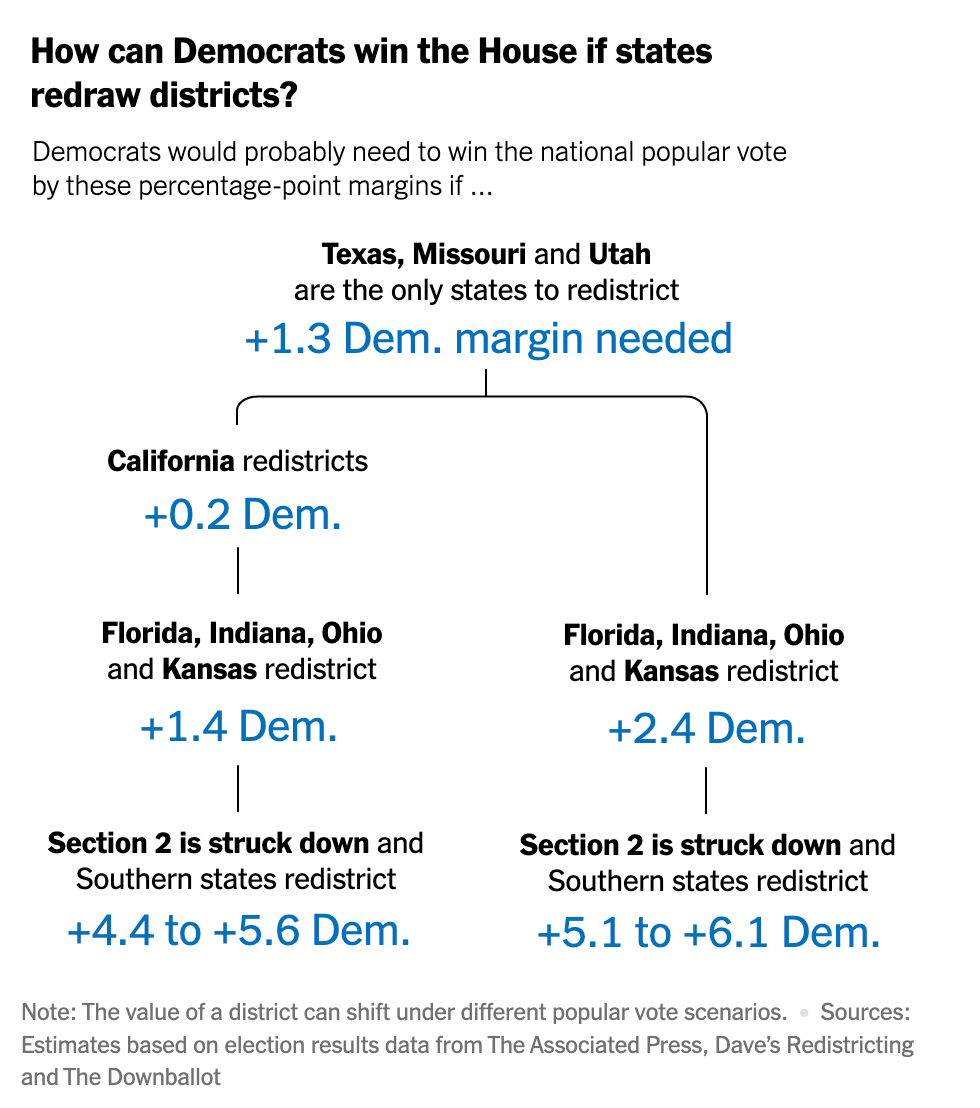

If the court strikes down — or weakens — Section 2 of the 1965 law, Republicans would stand to gain mightily. If the justices do so in time for Southern states to redraw their congressional maps before the 2026 midterms, when combined with other Republican mid-decade redistricting, Nate Cohn of the New York Times estimates that Democrats would have to win the nationwide House popular vote by around 4-5 percentage points next year to win a majority — or 5-6 points if a Democratic redistricting referendum fails in California.

According to one estimate by progressive groups, such a Supreme Court ruling could potentially unlock as many as 19 House seats in the South for Republicans.

Got it? OK, now forget everything I just told you. Whether that possibility excites or terrifies you, it is irrelevant to the legal merits of the case before the court, which asks a more fundamental question: Should those 19 seats have been walled-off in the first place? That isn’t to say the answer is purely legal, though (just that you should try to separate your partisan cheerleading when thinking about the correct outcome).

As I sat in the court’s press gallery yesterday, I heard the justices and lawyers bat around plenty of constitutional and statutory references. But it was also clear that the answer will ultimately be highly value-driven, hinging on competing visions of the role (or lack thereof) race plays in 21st century America and whether the equal-protection promise in the Constitution is broadly color-blind or more explicitly anti-racist.

The case, Louisiana v. Callais, stems from the 2020 census, which found that about one in three Louisianans were Black. When the state legislature drew its new congressional districts, though, only one out of six were majority-Black.

A group of Black voters sued under Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act (VRA), which seeks to prevent members of racial minorities from having “less opportunity than other members of the electorate…to elect representatives of their choice.” (The provision has long been interpreted as requiring some states to draw districts where racial minorities form a majority of voters — known as majority-minority districts — in order to prevent the sort of minority vote dilution described.)

A federal judge took their side and ordered Louisiana to create a map with two majority-Black districts, which was used for the 2024 elections. Then, a group of non-Black voters brought a challenge, arguing that they were discriminated against by the new map’s explicit use of race.

The Supreme Court first heard oral arguments in the case in March, but took the rare step of asking for another round of arguments before handing down its decision. For the second round, which took place yesterday, the justices asked each side’s attorneys to consider an added question: did the “intentional creation” of another majority-minority district violate the Constitution?

In essence: the 14th Amendment requires equal protection under the law; the 15th Amendment prohibits discrimination in elections on the basis of race. The VRA was designed to effectuate both promises. But by encouraging mapmakers to draw districts with racial lines as a consideration (in order to boost minority voting power), is Section 2 engaging in racial discrimination itself?

Four lawyers argued before the court, expressing three opinions. The NAACP’s Janai Nelson, representing the Black voters from the original suit, answered “no,” arguing that the VRA remains a necessary bulwark to ensure minority representation. “If we remove Section 2, we also recognize that there will likely be a resurgence of discrimination,” she told the justices.

State solicitor general Ben Aguiñaga, representing Louisiana (which has now turned against the map that was forced upon it by the courts), and Edward Greim, representing the non-Black voters, answered “yes.” They urged the court to strike down Section 2: “The Constitution does not tolerate this system of government-mandated racial balancing,” said Aguiñaga.

Hashim Mooppan, representing the Trump administration, did something unusual for the Trump administration: He struck a middle ground. Mooppan encouraged the justices to preserve Section 2, but to adopt a new, more restrictive standard when interpreting it.

We’ll look more closely at Mooppan’s proposal in a moment. First, let’s expand on the two value-driven questions I mentioned, which the justices were wrestling with on Wednesday:

Is the Constitution color-blind or anti-racist? By this, I mean: when the Reconstruction-era Amendments prohibited racial discrimination as slavery came to a end, did they mean that the government should never take race into account — or that race could be used as a factor if it was for the purposes of boosting minorities as a way to combat past or present discrimination?

“Race-based redistricting is fundamentally contrary to our Constitution,” Aguiñaga said on Wednesday, taking the former stance. “It requires striking enough members of the majority race to sufficiently diminish their voting strength, and it requires drawing in enough members of a minority race to sufficiently augment their voting strength.”

“Embedded within these express targets are racial stereotypes that this court has long criticized,” he added. “They assume, for example, that a Black voter, simply because he is Black, must think like other Black voters, share the same interests, and prefer the same political candidates.” In trying to dismantle racism, he said, the VRA was actually placing race at the forefront of the conversation, assuming voters would act differently based on the color of their skin.

Justice Sonia Sotomayor, in a pointed jab at her conservative colleagues, rebutted that color-blindness was impossible: race will always be part of these conversations, which means the VRA is a necessary protection for minority voters. “Race is a part of redistricting always,” Sotomayor said, adding: “Race is always a part of these decisions. And my colleagues are trying to tease it out in this intellectual way that doesn’t deal with the fact that race is used to help people.”

Sotomayor said that Aguiñaga was arguing that “you can use [race] to help yourself achieve goals that reduce a particular group’s electoral participation, but you can’t use it to remedy that situation.” Without the Section 2 protections, she added, “Blacks [would] never have a chance [to elect Black candidates], no matter what their number is, until they reach more than 51 percent.”

And if the Reconstructions amendments weren’t meant to be color-blind, should that still apply in 2025? This is a point that Justice Brett Kavanaugh repeatedly returned to. “This court’s cases in a variety of contexts have said that race-based remedies are permissible for a period of time, sometimes for a long period of time, decades in some cases,” he said Wednesday, “but that they should not be indefinite and should have a end point.”

“If it was ever acceptable under our color-blind Constitution to do this, it was never intended to continue indefinitely,” Greim said, referring to the use of race in redistricting. Aguiñaga said at one point that courts were focusing on discrimination in the “1930s, ‘40s, ‘50s, ‘60s,” adding elsewhere: “This stereotyping system has no logical end point. We are 40 years removed from Gingles [a key precedent in the case], and yet, according to my friends on the other side, nothing has changed in the voting and housing patterns in Louisiana that require race-based redistricting.”

Nelson, meanwhile, rebutted that the VRA wasn’t necessary because of discrimination in the 20th century: there is an “ongoing need for Section 2,” she said. “Even when white Democrats won an election in 2019, Black Democrats lost,” she said, referring to the election of Gov. Jon Bel Edwards in Louisiana. “My opponents here would like to make this a partisan issue because they believe the case law will enable their case to prevail. But it does not. This is about race.”

The attorney also made the point that even if a specific map ordered under Section 2 was mandated to be time-bound, “what is not grounded in case law is the idea that an entire statute should somehow dissolve simply because race may be an element of the remedy.”

On both these questions, many of the Supreme Court’s recent rulings would seem to favor opponents of the Voting Rights Act.

“The way to stop discrimination on the basis of race is to stop discriminating on the basis of race,” Chief Justice John Roberts wrote in a 2007 opinion, advocating a color-blind constitutional vision. Last year’s decision on affirmative action expressed a similar view — while also answering the second question of whether race-based advantages should be indefinite. “At some point—they must end,” Roberts wrote.

In his 2015 decision striking down a different section of the VRA, Roberts similarly expressed the view that whatever need may have existed for certain protections in the past, realities on the ground have changed enough to warrant a change in policy. “The conditions that originally justified these measures no longer characterize voting in the covered jurisdictions,” he wrote then.

The glaring exception is a case from 2023, Allen v. Milligan, when the Supreme Court considered an Alabama congressional map that a group of Black voters argued violated the VRA. Chief Justice Roberts, despite decades of skepticism toward the VRA, struck down the map, as did Justice Kavanaugh.

That’s why those two justices were particularly important to watch on Wednesday: if either one flips from their 2023 ruling in Milligan, Section 2 is likely to be limited. Roberts didn’t tip his hand much, although he did note at one point that Milligan “took the existing precedent as a given,” perhaps suggesting that he would handle this case differently now that the justices had explicitly asked both sides to bring arguments about whether the court’s Section 2 jurisprudence should be reconsidered.

Kavanaugh, meanwhile, seemed taken with the middle-ground charted by the Trump administration lawyer, asking each attorney to respond to it. The administration called for a modification — or “clarification,” as Justice Amy Coney Barrett urged them to describe it — of the court’s existing test for proving racial vote dilution, which was established in the 1986 case Thornburg v. Gingles (which some of the justices pronounced as “Gingles” and some pronounced as “Jingles”).

Under the Gingles test, to prove racial vote dilution, plaintiffs first have to prove that a certain racial minority group is “large and geographically compact” enough to form a majority-minority district, that the minority group is politically cohesive, and that the majority group frequently votes as a bloc to defeat minority-group candidates.

The Trump administration proposed tweaking the Gingles standard to be more open to maps that might leave minority voters with fewer representatives of their race — if a state can prove that the gerrymandering was with party, not race, in mind.

“One way of thinking about this is when you — if you think there’s a problem here — white Democrats in West Virginia, they don’t get districts drawn for them,” Mooppan, the Justice Department attorney pointed out. “White Democrats have zero representation in West Virginia, even though they’re a significant percentage of the state.”

Essentially, he argued, a 5-1 map favoring Republicans in a state outside the South wouldn’t be a problem, because everyone (including the Supreme Court) agrees that parties can manipulate congressional maps to their partisan advantage. It’s only an issue now, he said, because many of the Democratic voters in Louisiana happen to be Black.

“If these were white Democrats, there’s no reason to think they would have a second district,” Mooppan said. “None. And so what is happening here is their argument is because these Democrats happen to be Black, they get a second district. If they were all white we all agree they wouldn’t get a second district. That is literally the definition of race subordinating traditional principles.”

In that way, the entire argument took place under the shadow of Rucho v. Common Cause, the court’s 2019 decision that said partisan gerrymandering is acceptable under the Constitution. It was striking to hear the justices and attorneys alike so openly acknowledge that states tweak maps for their partisan gain.

“I think the reason [the Trump administration says] we haven’t really addressed their proposal before in our jurisprudence [is], in part, because, before Rucho, states wouldn’t articulate that objective explicitly and, therefore, it’s an open question” how the allowance of partisan gerrymandering plays into the matter, Kavanaugh said.

“Pre-Rucho,” the laws on partisan gerrymandering were unclear, Mooppan said. “But post-Rucho, it is totally clear that that is a permissible criteria.”

This lands us in an interesting place. Perhaps Black Democrats shouldn’t receive any extra representation in Louisiana that white Democrats lack in West Virginia solely on account of their race — but that argument presupposes that there is nothing wrong with either state limiting their numerous Democratic constituents from receiving representation on the basis of party, which, to be fair, is precisely what the Supreme Court has said.

To return to the question I posed at the beginning of the newsletter, this case could cause Democrats to lose more than a dozen House seats, since the VRA is the only thing preventing Republicans from carrying out total partisan gerrymandering in the South — but that still comes back to Rucho, which is the decision that allowed both parties to carve up maps for partisan gain in the first place. In light of the justices having acknowledged that a group of Democrats and Republicans who can form a compact majority in a certain area don’t have the right to a Democratic or Republican representatives, the question is now whether a group of Black or Hispanic voters who can do the same are owed a Black or Hispanic representative — and whether their argument along those lines is strengthened or weakened by the anti-discrimination language of the Reconstruction-era Amendments.

Wednesday’s hearing was the Supreme Court oral argument I’ve attended that most felt to me like a congressional hearing, with justices speaking at length to promote a specific side in the guise of asking questions — and all taking as a given the sort of partisan gamesmanship that has only expanded in this year’s explosion of gerrymandering. (In particular, at several points, Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson seemed to be prompting Nelson to make certain arguments, much like lawmakers will often tee up “friendly” witnesses with talking points.)

For her part, Nelson (in response to Kavanaugh’s persistent questioning on the proposal) dismissed the Trump administration’s new test as one that “would swallow Section 2 whole.”

“The fact that Black voters may correlate with voting Democrat or white voters may correlate with voting Republican does not deny the fact that there is racially polarized voting,” Nelson said. “And the totality of the circumstances, including the inability to elect Black candidates in Louisiana on a statewide basis for a number of offices — there’s never been a Black person in Louisiana elected statewide — is additional indicia that race is playing an outsized role in the electoral process in Louisiana.”

Nelson asked the justices to simply kick the case back down to the lower courts, with orders to come up with an alternative map that might better represent both Black and white voters.

No matter which side the court takes, the biggest variable is when they will rule: often, the justices leave decisions in major cases until June, but Louisiana has urged them to make a decision by December or January, to allow for time to create a new congressional map (if one is ordered) in time for the 2026 midterms.

However, the more dramatic the decision ends up being — and Louisiana is pushing for a dramatic rewriting of the court’s precedent — the longer it is likely to take.

One sign that the court might be considering more of a sweeping ruling: the fact that the case was held over for re-argument at all, something the justices rarely do. Sometimes, this is done in cases that end up being insignificant. But it has also been done in some of the most consequential cases in the court’s history: Brown v. Board of Education, Roe v. Wade, and Citizens United were all argued in front of the court twice, before going on to leave a mark for decades.

The question should not be about the outcome, it should be about the opportunity. It should be irrelevant that a majority black district tends to vote Democratic. The goal is to give them the opportunity to participate in the process in a non-discriminatory fashion.

What is the court’s justification which allows gerrymandering to favor one political party over another ??