Nebraska’s Electoral College ploy is nothing new

Political majorities in state legislatures have long tried to twist the Electoral College rules for partisan gain.

Good morning! It’s Wednesday, April 4, 2024. Election Day is 215 days away. If this newsletter was forwarded to you, subscribe here. If you want to contribute to support my work, donate here.

The eyes of the political world are rarely trained on Nebraska. Its congressional delegation is made up purely of Republicans; more than 15 years have passed since a Democrat there has won statewide office.

While most presidential battlegrounds are hotly contested because their electorates are divided evenly between the two parties, registered Republicans outnumber registered Democrats in Nebraska almost two to one. Unlike other key states, Nebraska factors into White House races not because of its split political composition, but because of its unique electoral system.

Along with Maine, it is one of two U.S. states that awards Electoral College votes by congressional district, not by winner-take-all. In the other 48 states, presidential candidates who win just 50.01% of the statewide popular vote are guaranteed 100% of a state’s electoral votes. But in both Maine and Nebraska, the statewide popular vote winners receive only two electoral votes; the rest are divvied up by congressional district, with candidates receiving one electoral vote for each of the state’s districts they win.

For years after Maine and Nebraska adopted this method, they still didn’t matter much on the presidential stage. But in 2008, Barack Obama won Nebraska’s 2nd district (Omaha and its suburbs), giving him one of the state’s five electoral votes. In 2016, the same thing happened in Maine, when Donald Trump won the state’s rural 2nd district. In 2020, both states split their electoral votes, with Maine’s 2nd going to Trump and Nebraska’s 2nd going to Joe Biden.

Ahead of the 2024 election, when every electoral vote could make a difference, Nebraska Republicans are trying to reengineer their system to avoid giving Biden a leg-up.

GOP state legislators are promoting a measure that would revert the state’s Electoral College selection method to winner-take-all. The state’s Republican governor, Jim Pillen, endorsed the efforts this week; so did Trump himself.

There’s not much time for the bill to be considered — the effort was dealt a setback last night and faces an April 18 deadline — but if it does end up advancing, it could make a big difference in the Trump/Biden rematch.

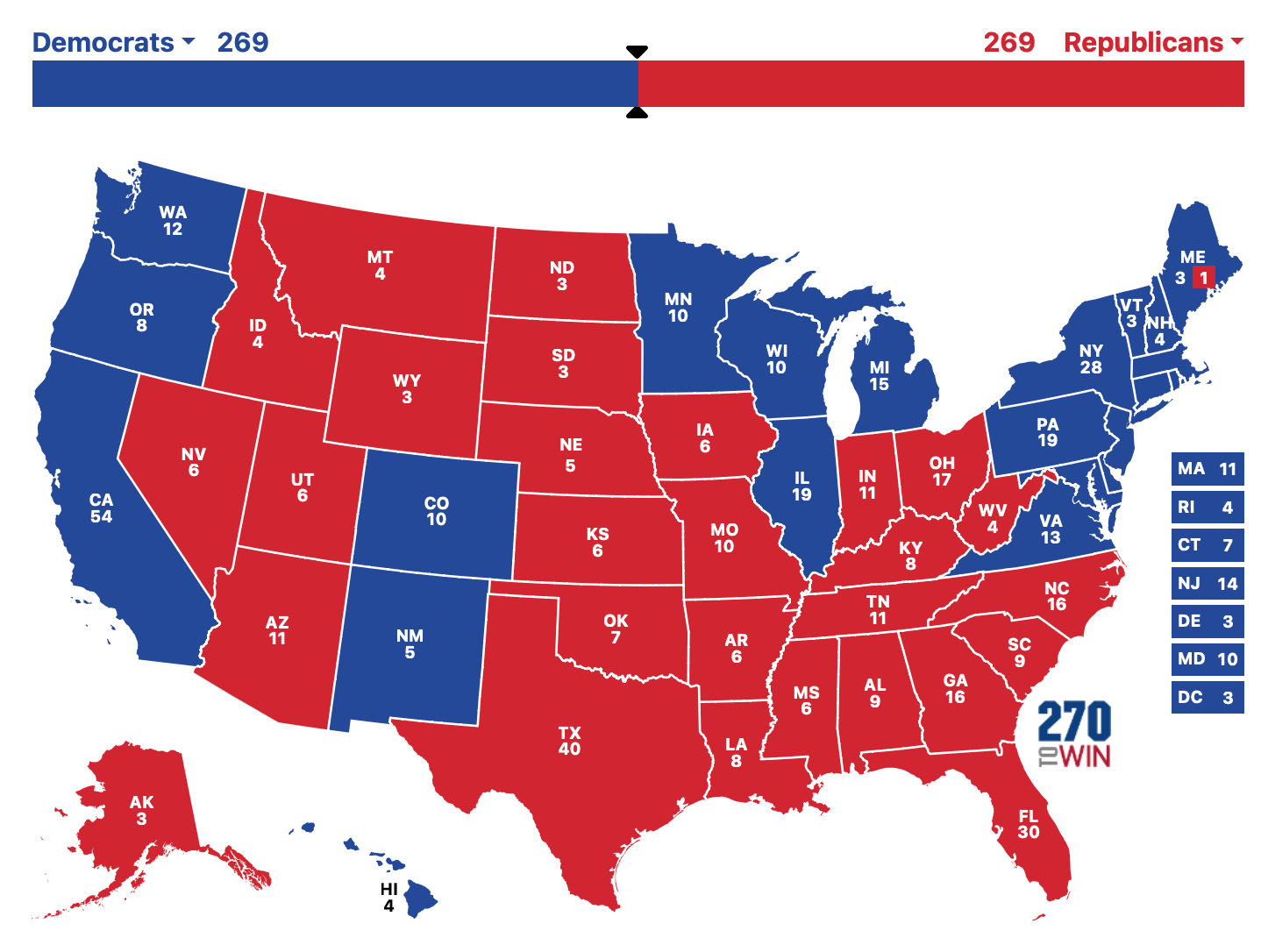

Let’s say that Biden wins the so-called “Blue Wall” states (Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin) this November and keeps Nebraska’s 2nd, but loses the other swing states he won in 2020 (Arizona, Georgia, and Nevada). This is a totally plausible scenario, according to current polling. If that happens, Biden would win the Electoral College by a hair, 270-268.

Now re-run that scenario, but with Nebraska awarding its electoral votes by winner-take-all. Suddenly, the election has been thrown into a 269-269 tie, which would spark a contingent election in the House — in which Trump would have the upper hand, because each state delegation would get one vote and Republicans are likely to control more House delegations.

Now you see why Democrats are so freaked out about Nebraska.

In the course of freaking out, however, some Democrats have forgotten their Electoral College history.

“It would literally take a complete distortion of all our rules” to update the method to winner-take-all, Nebraska state senator Wendy DoBer (D) said. “It would be incredibly unprecedented to try to make all of this happen now.”

Jim Messina, Obama’s 2012 campaign manager, waged a similar argument yesterday on MSNBC:

“I think this is what the modern Republican Party has become. They’re now trying to change the rules in the middle [of an election], trying to benefit themselves. This is the hell that Donald Trump hath wrought... There will be a national outcry for trying to change the rules here.”

But, as consequential as this change would be, it would not be “unprecedented” or even historically unique. This may be the first Electoral College change precipitated by Charlie Kirk, but it would be far from the first time a state has switched how it distributes its electoral votes for political reasons. Contrary to Messina’s assertion, that’s a “hell” that existed long before Donald Trump — and within both parties.

In fact, the classic example of pulling this maneuver comes courtesy of the Democrats, who executed a similar gambit in Michigan, way back in 1892 — in the midst of another heated presidential rematch.

This was the height of the Gilded Age, perhaps the last era to feature a political climate as closely divided as ours. Then, as now, presidential elections were routinely decided by a razor’s edge. In 1888, like in 2016, the loser of the popular vote had won the White House. Four years later, the defeated former president was returning to duke it out with his successor. (Sound familiar?)

Heading into the 1892 cycle, knowing the sequel would be as close as the original, Michigan Democrats were eager to give ex-president Grover Cleveland any advantage they could muster. So, they did the same thing that Nebraska Republicans are trying to do now: change their system of Electoral College allocation. In this case, they were switching to the opposite methods — going from a winner-take-all distribution to a congressional district distribution — but the desired outcome was the same: maximizing their candidate’s electoral votes.

This way, even if Republican president Benjamin Harrison won the statewide vote in Michigan, Democrats could ensure that Cleveland would still win some of the state’s electoral votes by winning Democratic-leaning congressional districts.

Republicans were just as worried about the ploy as Democrats are now. Here’s a pretty unique historical artifact, the letter Harrison wrote his campaign treasurer, Cornelius Bliss, expressing concern that more states would follow Michigan’s lead and change their Electoral College distribution:

“I see you have returned from your journey to Europe, I hope rested and refreshed and with good results to your family,” Harrison begins the letter. Acknowledging that Bliss is probably overwhelmed with business, “especially after an absence,” the president nonetheless requests that they soon discuss an urgent matter:

“I do not believe our people appreciate the possible significance and results of the elections in Ohio and Iowa, especially of the legislatures. If they carry the legislature in either or both of those states they will adopt the recent Michigan movement and provide for the election of electors of President and Vice President by Congressional districts and gerrymander the states so as to give them a preponderance of the electoral votes.”

Neither Ohio nor Iowa, nor any other additional states, ended up adopting the congressional district method, but the switch did make a difference in Michigan. Harrison ended up winning only nine of the state’s electoral votes, while Cleveland took five, padding his national victory.

Even though the extra Michigan electoral votes weren’t decisive — Cleveland still would have won the White House without them — they did spark a legal battle that established an important precedent: states can award electoral votes however they choose.

Republicans battled the change all the way to the Supreme Court, which ruled in McPherson v. Blacker — just three weeks before the 1892 election — that the Michigan legislature had every right to adopt the congressional district method if it wanted to. Chief Justice Melville Fuller wrote the following for a unanimous court:

“The Constitution does not provide that the appointment of electors shall be by popular vote, nor that the electors shall be voted for upon a general ticket, nor that the majority of those who exercise the elective franchise can alone choose the electors. It recognizes that the people act through their representatives in the legislature, and leaves it to the legislature exclusively to define the method of effecting the object.”

It would be decades before another state took the Supreme Court up on it. By the next election cycle, Republicans had regained power in Michigan and returned the state to winner-take-all status. The next state to adopt the congressional district method was Maine in 1969, followed by Nebraska in 1991.

The history of political parties trying to game Electoral College distribution goes back even farther than Cleveland v. Harrison. This is a point, by the way, that Republicans appear to have forgotten.

Nebraska Gov. Jim Pillen, in his statement endorsing the winner-take-all push, claimed that the method would “better reflect the Founders’ intent.” Trump echoed him on social media, falsely Truth’ing that winner-take-all is “what the Founders intended.”

But the Founders never expressed a preference for winner-take-all Electoral College distribution; in fact, the presidential elections they participated in used a range of elector selection methods. Here are all the different methods used in 1788, the contest that elected George Washington:

Three states used some form of selection by districts; only two allowed their state’s voters to assign electors by winner-take-all (the method supposedly “intended” by the Founders). The rest either had their state legislature appoint the electors, or used some combination of those methods.

The next several elections would see many states rotating between these systems, often to allow political leaders — including the Founders themselves — to gain a partisan advantage, as historian Robert Ross has written. In 1796, Thomas Jefferson’s Democratic-Republicans revised the rules in Pennsylvania to ensure a winner-take-all selection. In 1800, Alexander Hamilton tried to push New York towards the congressional district method as a way to block Aaron Bur’s campaign. (Why didn’t this important piece of history make it into the musical?)

This went on until the 1830s, when most states settled behind the popular vote, winner-take-all method. But South Carolina persisted in having its electors chosen by state legislators through the 1860 election. And other changes have come and gone, like Michigan’s brief switch in 1892. (Nebraska, for instance, only adopted its method in 1992 as an attempt to attract more candidate travel to the state. Republicans most recently sought to undo it in 2016, but they were blocked by a filibuster led by then-state Sen. Ernie Chambers, an iconoclastic political independent who was known for singing as he filibustered, suing God, and long being the only openly atheist state legislator in the country.)

Perusing Electoral College history, perhaps the most striking thing about the current efforts in Nebraska is that, by and large, no other states responded to the 2020 election by trying to change how their electors are awarded.

That’s the real historical anomaly here, considering the fact that almost every other controversial presidential election in history has led to attempts to reform the Electoral College:

The heated 1800 contest, which was decided by a contingent election, led to the 12th Amendment.

The 1824 election, also settled by the House, is what led most states to switch to winner-take-all selection. Meanwhile, a constitutional amendment to adopt the congressional district method nationwide receives a vote in Congress.

The 1876 election, decided by an independent commission, produced the Electoral Count Act.

The narrow 1888 election sparked the aforementioned Michigan switch.

The 1968 election, the last one in which a third-party candidate gained electoral votes, brought the U.S. the closest it has been to abolishing the Electoral College. (The House approved a constitutional amendment to do so, with Richard Nixon’s support, but it died in the Senate. Notably, one of the proposals considered at the time — as during the Constitutional Convention — was to keep the Electoral College, but have every state adopt the congressional district method.) This is also the election that inspired Maine to move to congressional district selection, as the three-way race inspired wider scrutiny of the winner-take-all method.

The 2000 election, decided by the Supreme Court, led to 1,500 electoral reform bills being introduced in the state legislatures and renewed support for Electoral College abolition.

The history buffs among you will note that this list includes four of the five elections in which the popular vote winner lost the presidency (1824, 1876, 1888, and 2000). The fifth, 2016, led to no similar movement to rejigger the Electoral College. Neither did 2020, a similarly controversial election (outside the limited auspices of the Electoral Count Reform Act). Unlike after 1824 or 1968, no constitutional amendments were considered in Congress; updating the text of the Constitution is now considered impossibly out of reach.

In my mind, this is part of a broader loss of civic imagination on the part of 21st-century Americans. We view our political system as this lumbering, immutable machine, even when many of its trademark facets are much newer than we think. As recently as the 1960s, the U.S. Constitution was amended four times in a single decade. Presidential candidates have only engaged in regular quadrennial debates since 1976. Government shutdowns originated in 1980. The Senate filibuster was rarely used until the late 2000s.

And changing Electoral College selection methods is by no means a Trump-era innovation, as Democrats have claimed this week, nor is the winner-take-all method a direct bequeathal from the Founders, as Republicans have stated. The methods states have used have historically been a lot more dynamic, whether to pursue political gain or due to more high-minded motivations.

If anything, the modern staleness in our election system is what’s new about it.

One more thing.

If you’re like me, the first question on your mind after reading all this about Electoral College selection methods is: What would it look like if the entire country used the Congressional District Method?

Luckily for you, I crunched the numbers, using congressional district data from Polidata. The main arguments for the Congressional District Method are that, unlike winner-take-all, it gives a voice to the political minority in a state and, therefore, could help avoid wild disparities between a candidate’s vote totals in the popular vote and the Electoral College.

Analyzing presidential races since 1992, I found that this is sometimes true. In 2020, for example, Joe Biden would have won 51.49% of electoral votes, much closer to his popular vote total (51.31%) than the winner-take-all method would give him (56.88% of electoral votes). In total, in six of the eight elections since 1992, all 50 states using the Congressional District Method would have produced results closer to the popular vote than every state using Winner-Take-All.

But the Congressional District Method wouldn’t have prevented the popular vote loser from winning the presidency in either 2000 or 2016 — and it would have elected the popular vote loser one additional time, in the 2012 election. If all 50 states took a page from Maine and Nebraska’s book, President Mitt Romney might be happily retired from his second term right now.

It isn’t hard to see why gaps between the popular vote and the Congressional District Method still persist (and are sometimes even larger than with winner-take-all). Gerrymandering can distort congressional districts to favor one party or the other; also, awarding two electoral votes to the statewide winner in each state can skew the totals.

A quick ask.

Today’s newsletter fulfilled a role that I hope Wake Up To Politics often brings to the table: offering historical context to help you better understand the day’s news.

In this case, I wanted to correct ahistorical accounts being told by both Democrats and Republicans — and correct the record on an episode that was being forgotten by many of my colleagues in the media. (“The district system was gone by the 1830s, and stayed gone for more than a century,” Vox reported yesterday. Not true, as you now know!)

I think excavating these episodes for our history can tell us something about our present, and help us separate the abnormal from the truly unprecedented. Politicians often claim that so-and-so action has no precedent — or that such-and-move is exactly what the Founders would have wanted. It’s incumbent on journalists to help you discover when those claims are and aren’t true.

But that kind of work takes time: in this case, a lot of diving through historical documents, journal articles, and Electoral College data. If you want to help support my ability to bring newsletters like this one to you, I hope you’ll consider donating to WUTP on a one-time or recurring basis. WUTP wouldn’t be possible without your support.

More news to know.

Politico: Biden’s not changing Israel policy after deadly strike on aid workers

Times of Israel: Hamas won’t budge on hostage deal demands, including end to war; Qatar says talks stuck

Axios: Israeli war cabinet member Benny Gantz calls for early elections

AP: Judge rejects Donald Trump’s request to delay hush-money trial until Supreme Court rules on immunity

Punchbowl: GOP shows little support for Trump immunity argument

Reuters: Two plead guilty to insider trading related to Trump Media merger

NYT: Trump Spoke Recently With Saudi Leader

Politico: Trump said he spoke with a slain woman’s family. The sister says he didn’t.

Axios: How Trump’s mind works

CNN: Greene keeps alive campaign to oust Johnson and warns against new push for Ukraine aid

The Hill: Cook Political Report shifts Nevada Senate race toward Republicans

The day ahead.

* The only event on President Biden’s public schedule is a reception for Greek Independence Day. Per Axios, he is also expected to hold a phone call with Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu; tensions are high between the two leaders following Biden’s condemnation of the Israeli air strike that killed seven aid workers, including one Americans.

* Vice President Harris will travel to Charlotte, North Carolina, where she will deliver remarks about climate change and attend a campaign fundraiser.

* The House and Senate are out until next week.

* The Supreme Court has no oral arguments scheduled.

Thanks for reading.

I get up each morning to write Wake Up To Politics because I’m committed to offering an independent and reliable news source that helps you navigate our political system and understand what’s going on in government.

The newsletter is completely free and ad-free — but if you appreciate the work that goes into it, here’s how you can help:

Donate to support my work or set up a recurring donation (akin to a regular subscription to another news outlet).

Buy some WUTP merchandise to show off your support (and score a cool mug or hoodie in the process!)

Tell your family, friends, and colleagues to sign up at wakeuptopolitics.com. Every forward helps!

If you have any questions or feedback, feel free to email me: my inbox is always open.

Thanks so much for waking up to politics! Have a great day.

— Gabe