A Reader’s Guide to the Comey Indictment

Everything we know about what James Comey is accused of.

Good morning, friends! All eyes in Washington today are on President Trump’s meeting with congressional leaders at 3 p.m. Eastern. Yes, this is the same meeting that was scheduled to take place last week, before it was canceled by Trump at the last minute. No, it’s not clear what’s changed since then, although it reportedly comes after Chuck Schumer and John Thune spoke on the phone for the first time in weeks.

Remember: The government shuts down at 12:01 a.m. on Wednesday unless the House and Senate approve a temporary funding bill. So there is no small amount of pressure for a deal to come out of this meeting, even if neither side sounds very optimistic that one will. (Also worth keeping your eye on: President Trump will meet with Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu today, followed by a press conference at 1:15 p.m. ET. Big day at the White House.)

I’ll have much more for you on the shutdown talks tomorrow, and throughout the week. Today, we have other business to discuss:

The main goal of this newsletter, put simply, is to peel back the curtain in Washington and make the workings of American government accessible to all Americans.

There are other news outlets that try to do that too, of course. One of the things that consistently annoys me about many of them is they do that by trying to excessively summarize things — like what a piece of legislation says or what an executive order will do — which can often leave the reader with a vague, or even misleading, sense of the details of a government action.

Here at Wake Up To Politics, I try to practice a “show, don’t tell” philosophy, by laying out for you the primary source documents that are driving the political process. I think some outlets (and, then, some readers) assume this will be too overwhelming, which is why they end up sanding things down to make them “readable.” But, actually, a lot of these documents are not hard to read for yourself, and in almost every case, you will better understand something for having read them yourself.

I did this recently with a six-part series breaking down the One Big Beautiful Bill. This morning, I’m expanding my “Reader’s Guide” franchise, with a document that is much shorter, but also consequential: the indictment of former FBI Director James Comey. As with the Big Beautiful Bill guides, we won’t only dwell on the main text itself. I’ll also bring in other primary sources as context — statutes, congressional testimony, inspector general reports — to give you a full understanding of what Comey has been accused of.

Before we start reading, an important question: How would you go about finding this document for yourself? For pieces of legislation, the best place to go is congress.gov. For court documents, I recommend courtlistener.com, which maintains an extensive and enormously useful database. Here is the link to their page for United States v. Comey, which you can bookmark; whenever anything is added to the Comey docket, that page will be updated.

The very first entry on the docket: “INDICTMENT as to James B. Comey, Jr. count(s) 1, 2.” Here is the link. Let’s start reading.

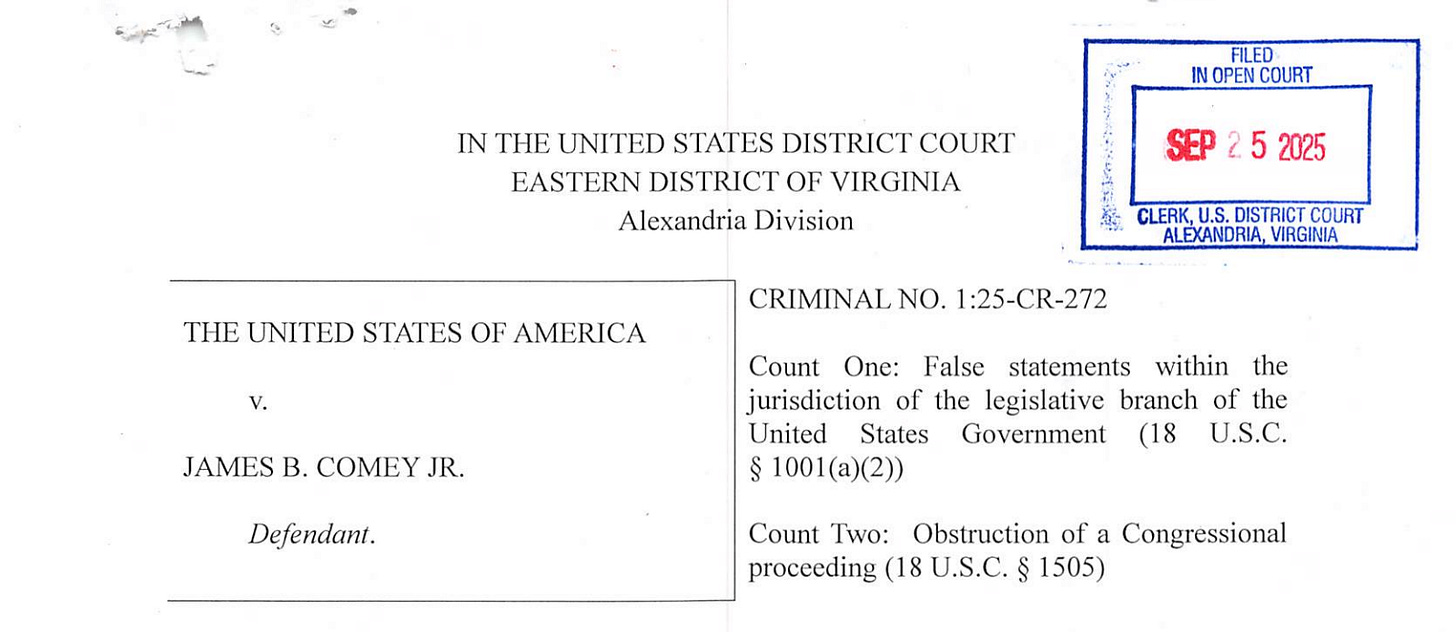

OK, here’s the top of Page 1, which will help us situate ourselves. The name of a case is called its “caption,” and the first name in a caption is always the party bringing the case. So, if James Comey was suing the United States, it would be called Comey v. United States. (Incidentally, CourtListener tells us, a similarly named case does exist, Comey v. United States Department of Justice, which is a lawsuit brought by Comey’s daughter Maurene challenging her firing as a federal prosecutor.)

But, here, the United States is prosecuting Comey, so our case is The United States of America v. James B. Comey Jr. (If Comey were to lose his case at the trial court level and then appeal, he would then be the one bringing the case and it would become Comey v. United States.)

The header of the indictment also includes a summary of the two counts Comey has been charged with, as well as the venue. There are 94 federal district courts in the United States; Comey has been charged in the Eastern District of Virginia, at its courthouse in Alexandria. This is because the indictment centers around testimony Comey gave to Congress remotely during the pandemic, speaking over videoconference from his home in McLean, Virginia.

Now, onto the substance of the indictment:

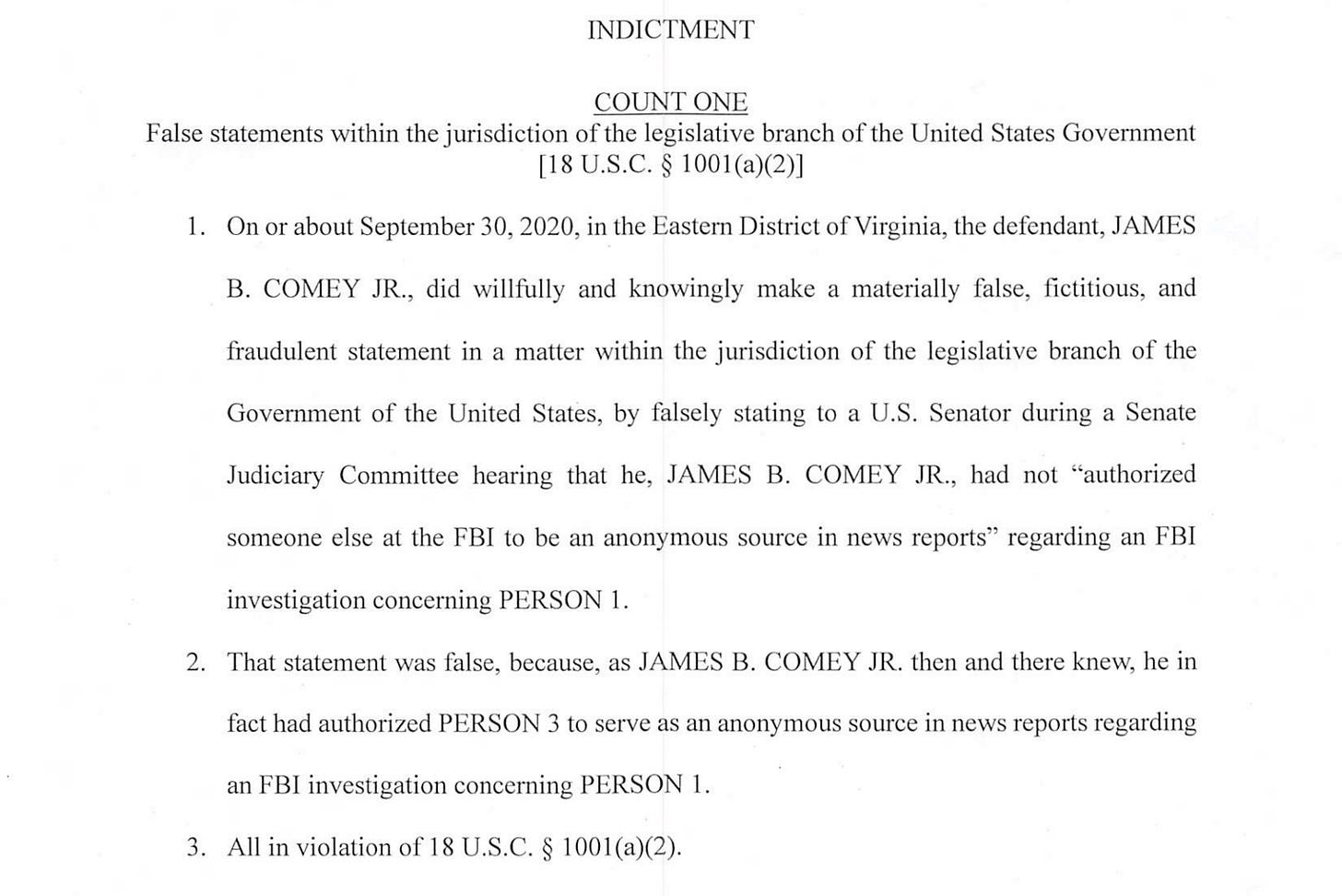

As noted above, Comey is being hit with two felony charges. The first is a violation of 18 U.S. Code § 1001(a)(2), which makes it a crime to “knowingly and willfully” make a “materially false, fictitious, or fraudulent statement or representation” in “any matter within the jurisdiction of the executive, legislative, or judicial branch of the Government of the United States.”

The punishment for this crime is a fine (of up to $250,000, per 18 U.S. Code § 3571) and/or up to five years in prison.

The allegation here is that Comey “falsely stated to a U.S. Senator during a Senate Judiciary Committee hearing” on September 30, 2020 “that he, JAMES B. COMEY JR., had not ‘authorized someone else at the FBI to be an anonymous source in news reports’ regarding an FBI investigation concerning PERSON 1.”

“That statement was false,” the indictment says, “because, as JAMES B. COMEY JR. then and there knew, he in fact had authorized PERSON 3 to serve as an anonymous source in news reports regarding an FBI investigation concerning PERSON 1.” (Why isn’t there a Person 2? We’ll get to that later on.)

At this juncture, let’s bring in another primary source and look at the section of Comey’s 2020 testimony at issue:

SEN. TED CRUZ: On May 3rd, 2017, in this committee, Chairman Grassley asked you point blank, “Have you ever been an anonymous source in news reports about matters relating to the Trump investigation or the Clinton investigation?” You responded, under oath, “Never.”

He then asked you, “Have you ever authorized someone else at the FBI to be an anonymous source in news reports about the Trump investigation or the Clinton administration?” You responded, again under oath, “No.”

Now, as you know, Mr. McCabe, who works for you, has publicly and repeatedly stated that he leaked information to the Wall Street Journal and that you were directly aware of it and that you directly authorized it. Now, what Mr. McCabe is saying and what you testified to this committee cannot both be true. One or the other is false. Who’s telling the truth?

JAMES COMEY: I can only speak to my testimony. I stand by the testimony you summarized that I gave in May of 2017.

CRUZ: So your testimony is you’ve never authorized anyone to leak? And Mr. McCabe, if he says contrary, is not telling the truth, is that correct?

COMEY: Again, I’m not going to characterize Andy’s testimony, but mine is the same today.

The first thing you might notice here is that the quote that seems to be attributed to Comey in the indictment — that he had not “authorized someone else at the FBI to be an anonymous source in news reports” — was never actually uttered by Comey at the September 2020 hearing.

In fact, it was never uttered by him (at least, not in a public setting under oath). Instead, that is a quote of Sen. Chuck Grassley (R-IA), who asked Comey at a May 3, 2017 hearing if he had “ever authorized someone else at the FBI to be an anonymous source in news reports about the Trump investigation or the Clinton investigation.” Comey, at the time, said “No,” and then Sen. Ted Cruz (R-TX) repeated the exchange back to him in 2020 (though accidentally saying “Clinton administration,” not “investigation”) and Comey stood by his testimony.

If the underlying testimony is not true, why not cut out the middleman and charge Comey for lying in 2017? Well, non-capital offenses in the U.S. generally have a five-year statute of limitations, which means that would have had to be done by 2022. So, the Trump administration is left with using Cruz’s rehashing (and Comey’s endorsement) of the testimony on September 30, 2020. (You might notice that the statute of limitations for Comey lying in 2020 was set to run out tomorrow, precisely five days after the indictment was filed.)

I will leave it to the lawyers to hash out whether it poses a problem for the Trump administration that they allege Comey “stated” something he never directly said. For our purposes, I’m more interested in the substance of the allegation, so we’ll agree here that Comey did, at least, indicate (in both 2017 and 2020) that he did not authorize anyone at the FBI to leak information about the Trump or Clinton probes. (But don’t be surprised if this “state” vs. “indicate” difference comes up later on, as a way for Comey’s defense team to challenge the strength of the indictment.)

Because Cruz, in the 2020 hearing, challenges the veracity of Comey’s testimony by bringing up former FBI Director Andrew McCabe, a lot of commentators have assumed that the unidentified “Person 3” in the indictment (the allegedly-Comey-authorized leaker) is McCabe and “Person 1” (the subject of the investigation being leaked about) is Hillary Clinton. In the hearing, Cruz asserts that McCabe has claimed that Comey authorized him to leak to the Wall Street Journal.

This isn’t quite the case. According to a 2018 Justice Department inspector general’s report, which investigated leaks in the 2016 Journal article, “FBI in Internal Feud Over Hillary Clinton Probe,” Comey and McCabe differ on whether McCabe told Comey (after the fact) that McCabe had authorized a leak for the article. McCabe says he did (and that Comey said, after the fact, that it was a good idea); Comey says he didn’t.

For what it’s worth, the IG found that “the overwhelming weight of evidence supported Comey’s version of the conversation and not McCabe’s” and concluded that McCabe falsely claimed that he told Comey about the leak the day after the article was published. But, either way, even if such a conversation took place, the only claim is that it took place after the article came out, which means this can’t be an example of Comey authorizing a leak. (To put a finer point on it, McCabe himself said yesterday that Comey never authorized him to leak, contrary to Cruz’s claim that he had said otherwise.)

Indeed, it has now been reported by ABC News that “Person 1” is Clinton, but “Person 3” is Daniel Richman. So if you see anyone debunking the indictment by laying out the fact pattern I detailed above about McCabe (which many people are trying to do!), they are mistaken: McCabe is not at issue here. (And McCabe wasn’t even interviewed as part of the investigation. There is a separate question about whether Comey thought Cruz was asking about McCabe, and intended his answer to be a narrow denial of authorizing McCabe to leak, but — in my opinion — Cruz’s question and Comey’s answer make clear that they are talking more broadly about whether Comey had ever authorized anyone at the FBI to leak about Trump or Clinton.)

Daniel Richman is a Columbia Law professor who has been friends with Comey since they served as assistant U.S. attorneys together in New York. In 2015, Comey instructed the FBI to hire Richman as a “special government employee” (SGE) with Top Secret clearance. Importantly for this story, as of January 2017, Richman was still an SGE. (Again, I’ll leave it to others to debate the narrow legal question of whether an SGE counts as “someone else at the FBI.” This is somewhat like asking, was Elon Musk “someone at the White House” in January 2025? For the moment, though, I’m less interested in litigating word choices than finding out what we know about what Comey is accused of, authorizing a leak to Daniel Richman).

According to a 2021 FBI investigative memo that looked into leaks by Richman, which was published by a right-wing news outlet last month, Richman was hired to be part-consigliere, part-media whisperer for Comey: “someone outside of the FBI’s regular leadership” who Comey could “discuss sensitive matters, including classified information, with” and who could also serve as a “liaison to the media,” so that Comey could get his narrative into news stories without having his fingerprints or the fingerprints of the FBI’s official press office attached.

(If you want to sound cool while discussing the Comey probe, you can let slip to friends that the FBI probe into Richman was known as “Arctic Haze,” and the original Hillary Clinton email investigation was known as “Midyear Exam.”)

To the extent Richman is “famous” (a low extent), he is most famous for being the one to leak Comey’s memos about his interactions with Donald Trump in 2017. But, as stated, the Comey indictment is about the investigation into Clinton, not Trump. The “Arctic Haze” memo contains a fair amount of redactions, but it seems like the key thing Comey/Richman are suspected of leaking was about Loretta Lynch.

Lynch, you might recall, was Attorney General for the last two years of Barack Obama’s administration. She oversaw the Hillary Clinton email probe, until a firestorm broke out about her meeting with Bill Clinton on a tarmac in Phoenix, after which she announced that she would defer to the FBI’s (read: Comey’s) decision about whether to charge Clinton, in order to remove the appearance of impropriety.

In 2017, Comey was facing heat for his handling of the Clinton probe, especially his decision to make a public statement criticizing Clinton while announcing that she wouldn’t be charged, which Comey has partially attributed to the need to bring transparency to the investigation after Lynch evoked suspicions of politicization.

Per the “Arctic Haze” memo, Richman told investigators that Comey told him in January 2017 that the tarmac meeting was not the only thing on his mind in this regard. From the memo:

Richman recalled Comey told him there was some weird classified material related to Lynch which came to the FBI’s attention. Comey did not fully explain the details of the information. Comey told Richman about the Classified Information, including the source of the information. Richman understood the information could be used to suggest Lynch might not be impartial with regards of the conclusion of the Midyear Exam investigation. Richman understood the information about Lynch was highly classified and it should be protected. Richman was an SGE at the time of the meeting.

Richman told investigators that, shortly thereafter, he had a conversation with New York Times reporter Michael Schmidt in which Schmidt brought up this exact classified information. Richman said that he was pretty sure he didn’t tell Schmidt about the information, sure “with a discount” he didn’t confirm it, and that Schmidt knew more about the information than him anyway.

(It’s not entirely clear what the information is, other than it’s clearly something that makes Lynch look bad and makes Comey’s desire to make the Clinton non-indictment look less political more understandable. Schmidt’s subsequent article refers to a “document obtained by the FBI” that was “written by a Democratic operative who expressed confidence that Ms. Lynch would keep the Clinton investigation from going too far.” The document had been obtained by Russia, and Comey was reportedly worried that Russia could leak it after it was announced that Clinton wasn’t facing charges, as a way to tar the investigation.)

But back to the present day. It’s not clear whether the Comey indictment turns on Richman’s conversation with Schmidt about the Lynch information, although that’s the information that appears to have been investigated most closely in the “Arctic Haze” probe. (At least in the unredacted version.) For what it’s worth, Richman told the investigators in 2017 that “Comey never asked him to talk to the media,” and investigators said they did not find “sufficient evidence” to charge either Comey or Richman with “making false statements or with the substantive offenses under investigation.”

But there’s also this in the memo:

According to the New York Times, Richman’s interview with prosecutors this month was “not helpful in their efforts to build a case,” so presumably he told the DOJ the same thing he told the “Arctic Haze” investigators. So if the DOJ has a meaningful case against Comey, it’s probably contained in these redactions: everything after “Although Richman later told the interviewing agents Comey never asked him to talk to the media…”

Of course, since it’s redacted, we can’t really judge much more, but that about sums up what we know about Count 1 (from the indictment and other primary sources): it turns on whether Comey authorized Daniel Richman to leak to the media (about Hillary Clinton and potentially also about Loretta Lynch), and then whether he “knowingly” lied in 2020 about having done so.

We don’t yet know the specific information Comey is alleged to have lied about, so it’s too early to opine on whether he did lie and certainly on whether he “knowingly” did so, which is a separate legal question, but — if you return to the part of the U.S. Code we started with — an equally important one prosecutors will have to prove.

On to Count Two:

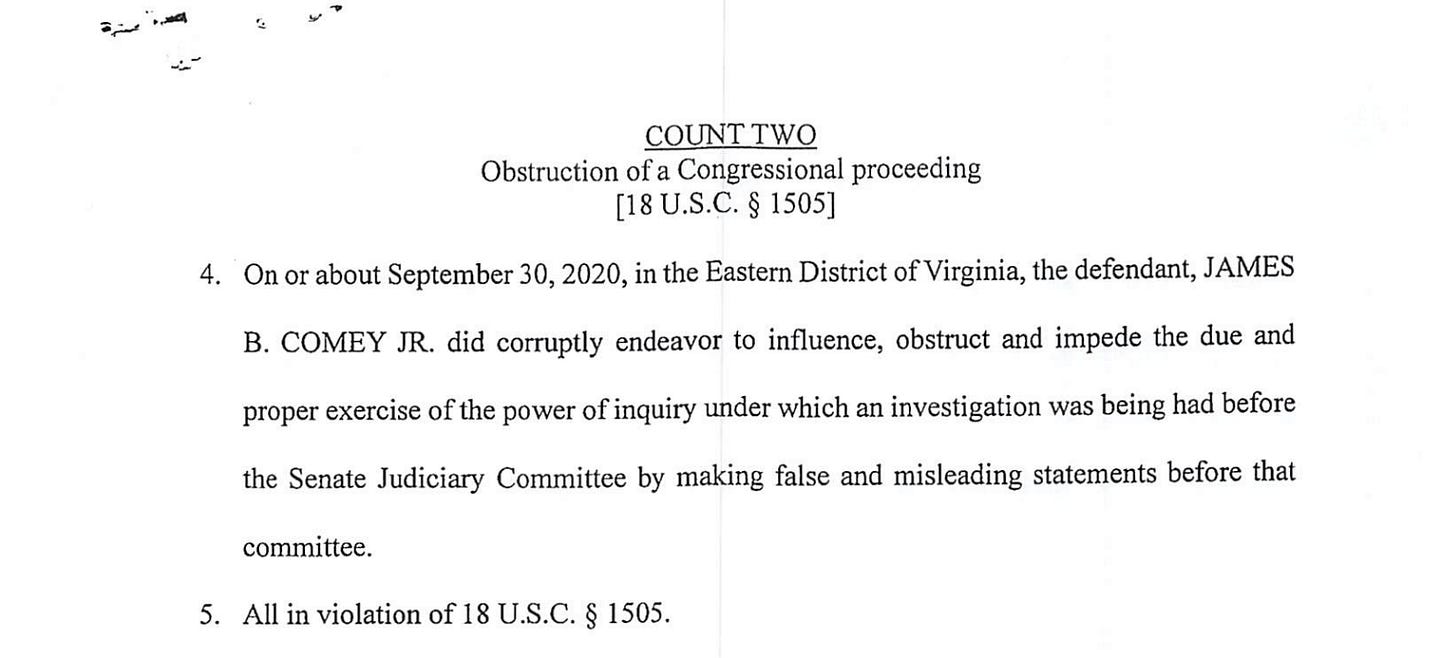

This one requires less additional context. The alleged violation here is of 18 U.S. Code § 1505, which makes it illegal when someone “corruptly…endeavors to influence, obstruct, or impede” the “due and proper exercise of the power of inquiry under which any inquiry or investigation is being had by either House, or any committee of either House or any joint committee of the Congress.”

The punishment is the same as the crime from Count One, which means Comey would be facing a maximum 10-year prison sentence and $500,000 fine if found guilty on both counts and hit with the highest possible sentence.

Count Two appears to turn on the same fundamental conduct as Count One: making a false statement to the Senate Judiciary Committee on September 30, 2020. The (unknown) false statement from Count One is presumably the same as the false statement in Count Two, although the indictment does not say so for certain.

And then, the end:

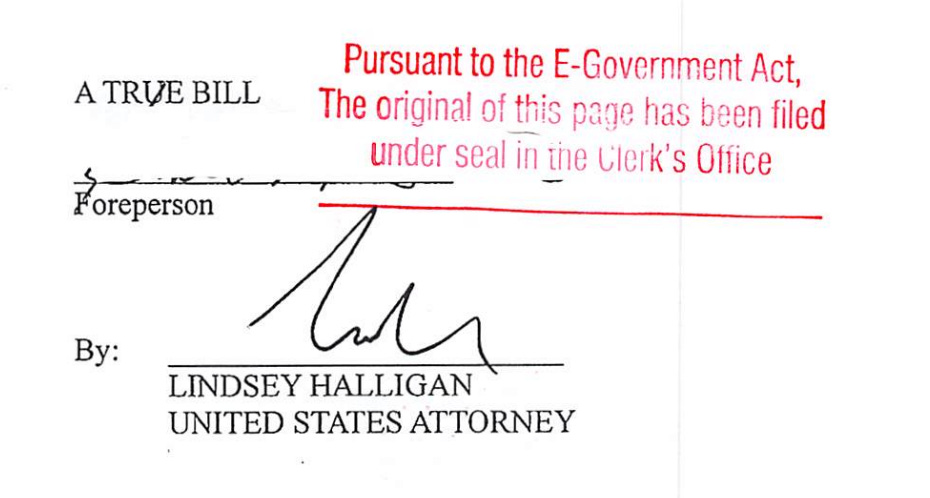

Beneath Count Two, the indictment is signed by the foreperson of the grand jury that indicted Comey, which affirms that this is a “true bill” (meaning that the grand jury found probable cause that Comey committed the alleged crime). The indictment is also signed by Lindsay Halligan, the acting U.S. Attorney for the Eastern District of Virginia, who was installed by Trump just last week in a Truth Social post that specifically mentioned Comey.

This is notable because indictments are usually signed by career prosecutors, not the top official in a U.S. attorney’s office. But Halligan — who previously served as a personal lawyer for Trump — reportedly presented the case to the grand jury herself, her first time ever prosecuting a case, after receiving a memo from career prosecutors saying they didn’t believe there was sufficient evidence to bring charges against Comey.

This is why you should always read the primary sources, and read them all the way to the end! The fact that Halligan is the only prosecutor who signed the indictment is unusual, and a telling sign of the support for this indictment within the prosecutor’s office.

Now, I know that was a lot — we had to burrow through a lot of layers, from Comey to Richman to Lynch to Schmidt — but there’s one more document we have to look at.

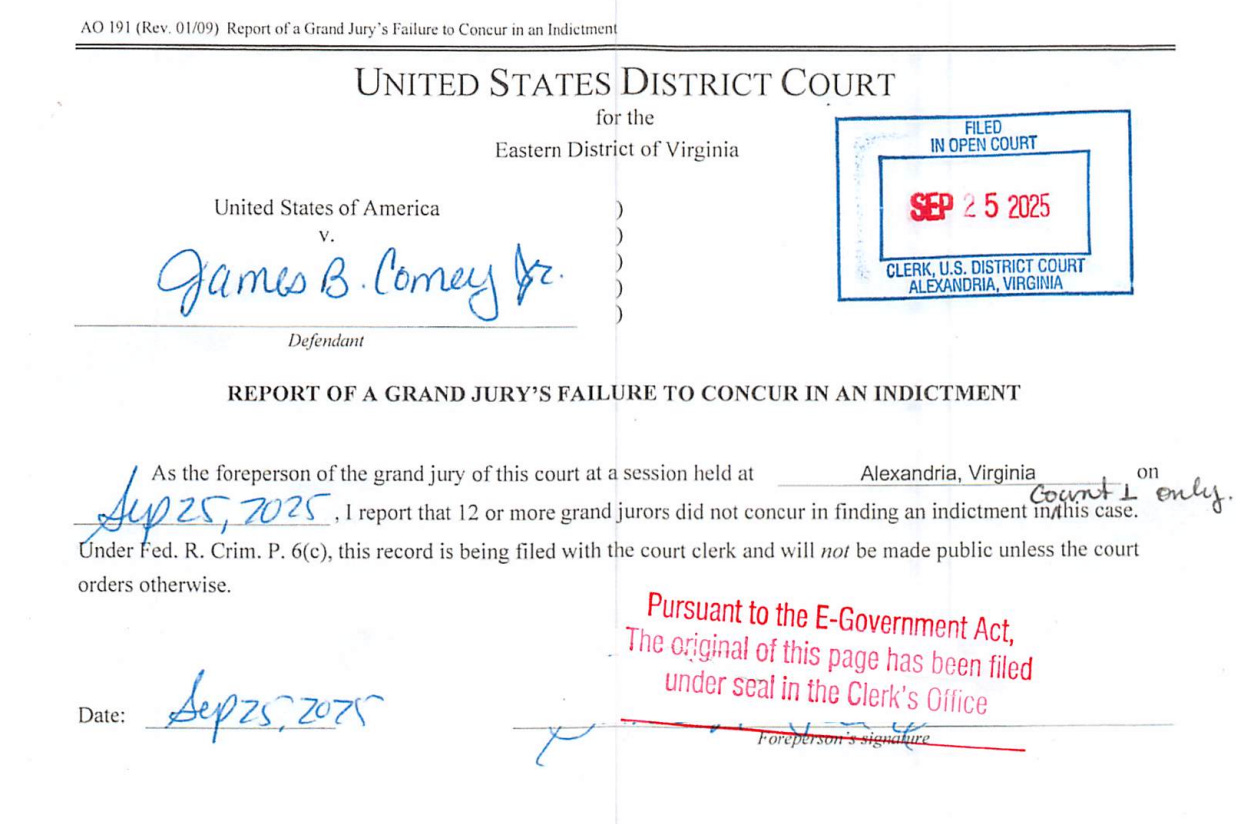

Because the next entry on the Comey document is: “Report of a Grand Jury’s Failure to Concur in an Indictment by USA as to James B. Comey, Jr.” That sounds interesting:

Here, we see the foreperson informing the judge that the grand jury did not find a true bill of indictment — though they clarified, in pen, that the “no true bill” applied only to one count.

Federal grand juries range in size from 16 to 23 members. 12 are needed to indict. This document shows that at least that many declined to sign on to the first charge Halligan tried to bring; we also know that only 14 grand jurors signed onto the other two charges, which means at least two jurors (and potentially more, if it was a larger grand jury) also declined even to sign on to the charges that were successful.

It is very rare for grand juries to decline to bring charges requested by prosecutors — in 2010, for example, federal grand juries were presented with 162,300 proposed indictments; they refused to sign off on only 11 of them — so the declination of the first charge and the dissents on the other two charges are highly notable.

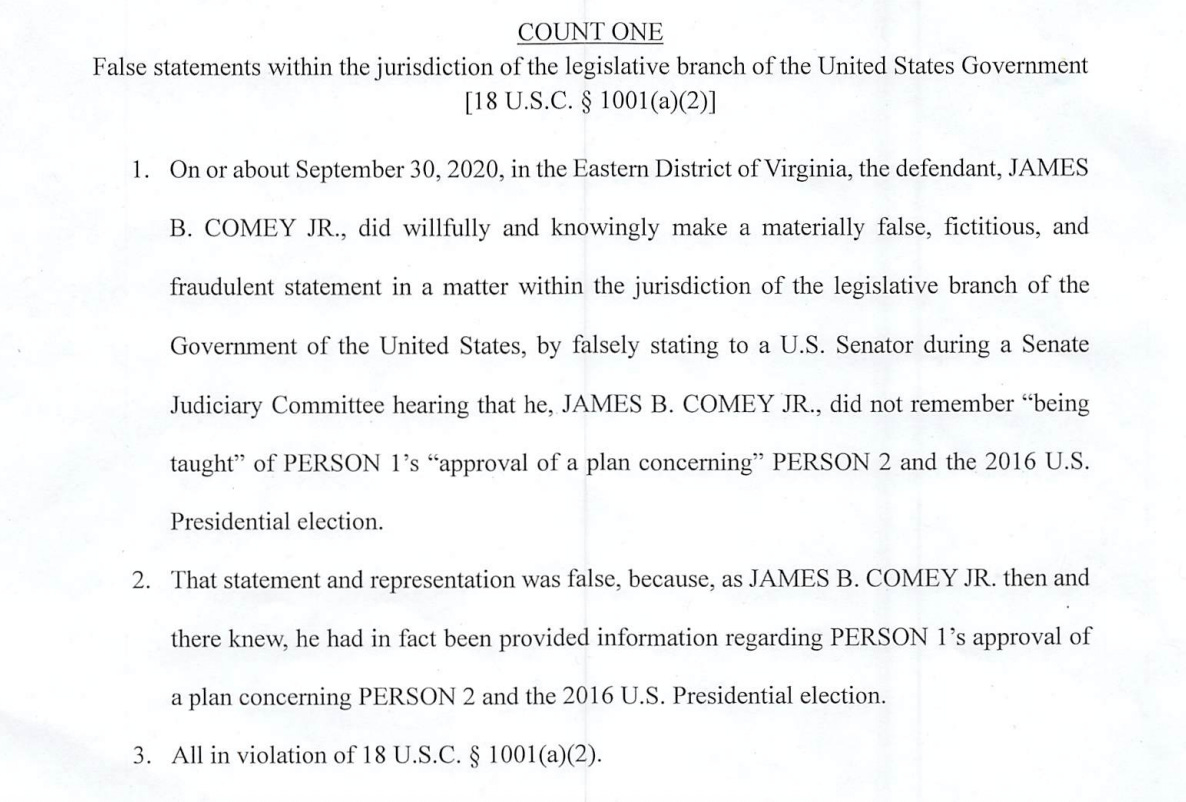

The “no true bill” document reveals the declined charge, the would-be Count One:

This was going to be another false statements charge, again from Comey’s September 2020 testimony.

This exchange was with Sen. Lindsey Graham (R-SC), who asked Comey if he recalled “being taught” by U.S. intelligence officials in 2016 of “Hillary Clinton’s approval of a plan concerning U.S. presidential candidate Donald Trump and Russian hackers hampering U.S. elections as a means of distracting the public from her use of a private email server.” (At last, our mysterious “Person 2”! It was going to be Donald Trump.)

“That doesn’t ring any bells with me,” Comey replied.

To quickly wrap up this story, that question pertained to information declassified by the first Trump administration stating that U.S. intelligence agencies obtained a “Russian intelligence analysis” in 2016 suggesting that Clinton had “approved a campaign plan” to “stir up a scandal” against Trump by tying him to Russia’s hacking of her campaign emails.

The Trump administration itself noted that it did “not know the accuracy” of this Russian allegation, which the FBI reportedly investigated but never verified.

The only thing known on the public record is that intelligence officials “forwarded an investigative referral” about the alleged “campaign plan” to Comey and another FBI official in September 2016. To prove this charge, prosecutors would have had to prove not only that Comey saw and was aware of the referral in 2016, but also that he remembered it in 2020 and was knowingly lying when he said otherwise.

Of course, it’s a moot point now.

So, what happens next?

Comey is set to be arraigned on October 9 at the courthouse in Alexandria, where it appears he will plead not guilty.

There is then a range of motions his defense team can make. For starters, Rule 7 of the Federal Rules of Criminal Procedure says that an indictment “must be a plain, concise, and definite written statement of the essential facts constituting the offense charged,” a standard for which this indictment certainly does not go above and beyond. (Not all indictments are “speaking indictments,” which lay out a broader narrative rather than just the “essential facts,” but this one is especially bare-bones for such a high-profile case.)

But Rule 7 also adds:

The court may direct the government to file a bill of particulars. The defendant may move for a bill of particulars before or within 14 days after arraignment or at a later time if the court permits. The government may amend a bill of particulars subject to such conditions as justice requires.

As stated, it’s hard to judge this indictment because there’s such little information in it: it says Comey lied to Congress about authorizing a leak, but doesn’t even say what the leak was (or give any evidence that he authorized it). A “bill of particulars,” which Comey can request, would offer additional information. (However, some legal commentators have speculated that Comey could not ask for one, and invoke his right to a speedy trial, in order to deny Halligan preparation time and use the vagueness of the original indictment against her at trial.)

Comey could also file motions seeking dismissal of the case on the grounds of “vindictive” or “selective” prosecution, based on the many comments by President Trump calling for Comey to be indicted.

“Vindictive prosecution,” according to a 1982 Supreme Court opinion, is when someone is being “punished for exercising a protected statutory or constitutional right.” This is almost always used in the context of the criminal process — e.g. a prosecutor hitting someone with additional charges (or requesting a tougher sentence) because they declined to plead guilty or appealed their conviction — although theoretically Comey could try to argue he is being prosecuted for using his First Amendment rights to speak out against the president.

To dismiss a case due to “selective prosecution,” according to a 1996 Supreme Court opinion, a defendant needs to prove that they were prosecuted due to an “arbitrary classification such as race or religion” (here, presumably, it would be political affiliation) and that “similarly situated individuals” weren’t prosecuted for the same crime.

By way of example, at least two defendants have tried to have cases dismissed for vindictiveness and selectiveness under the Trump administration so far: Kilmar Abrego Garcia and Rep. LaMonica McIver (D-NJ).

Abrego Garcia cited the fact that “no similarly situated defendant—an alleged driver in an alien smuggling conspiracy—has ever had to wait two and a half years [after being stopped while driving] to be charged with a crime where the facts had not changed since the stop itself,” while McIver pointed out that the Trump DOJ has dismissed cases against January 6th rioters accused of assaulting law enforcement officers, which is the same offense she has been accused of.

Don’t be surprised if Comey attempts to pull a similar move, although he’d likely have to surface examples of “similarly situated” Trump allies lying to Congress — and going uncharged — to be successful.

Your articles are always the most respectful--of the reader--I've ever read. I always feel smarter after reading your pieces. You give us just the facts and otherwise provide the primary sources and leave it up to us to read them. You do not insult our intelligence. Thank you! I recommended your site to many people based on that alone, but of course you also treat timely topics.

Thank you so much for your very informative articles. I have learned so much from reading your column. I feel like I am taking an enjoyable and very interesting civics class. You have become my main source of political news since there are so few people I trust to present the news fairly. I understand the reaction of those who fear the Trump administration is trampling on individual rights and freedoms. But you present the news in a straight forward way and let us draw our own conclusions. I respect that.