Presidential rematches throughout history

Trump vs. Biden wouldn’t be the first time two presidential rivals have faced off against each other twice.

Good morning! It’s Tuesday, May 23, 2023. The 2024 elections are 532 days away.

Leading today’s newsletter: A history lesson! I’ll answer a reader question by taking you on a tour through the history of past presidential rematches — with an eye towards what they might tell us for 2024.

If this newsletter was forwarded to you, subscribe here. If you want to contribute to support my work, donate here.

Ask Gabe: How have previous presidential rematches gone?

According to a recent NBC News poll, 70% of Americans don’t want Joe Biden to run for president in 2024. 60% feel the same way about Donald Trump.

And yet, the two men are — once again — the frontrunners for their party’s presidential nominations. The U.S. is hurtling towards a high-stakes rematch that almost no one wants.

The despair many voters feels towards a 2020 re-run was highlighted yesterday by a piece in the Washington Post, which covered the findings of a recent focus group made up of 15 swing voters who supported Trump in 2016 and Biden in 2020.

Nine of the 15 were leaning towards voting for Biden again, while three said they planned to go back to supporting Trump. (The other three said they wouldn’t vote or would support a third-party candidate.) But few of the focus group members sounded all too pleased with their options.

“I think we need more choices — both parties,” one member of the focus group, a 44-year-old antiques salesman from Philadelphia, said. “Fresh faces, fresh ideas, youth and youthfulness, everything.”

Or as Rich Thau, the focus group moderator put it: “For these voters, deciding between Trump and Biden is like being forced to choose either a demolition derby car or an old clunker for a cross-country trip. With either choice, they are not particularly happy.”

That serves as the perfect jumping-off point to answer a reader question I recently received, which will send us delving into the history of presidential rematches past...

Regina L. asks: “With the strong possibility of a Trump vs. Biden matchup in 2024, would this be the only time in history where the same two candidates ran against each other in back-to-back elections?

It actually wouldn’t! In fact, out of the 59 elections in presidential history, a full 10% of them — six — have been rematches of the previous contest:

1796 and 1800

The first two contested presidential elections in U.S. history consisted of the same candidates, John Adams and Thomas Jefferson. Adams won the first go-around, but because the Constitution originally called for the presidential runner-up to serve as vice president, it meant that Jefferson was Adams’ own VP when he (successfully) came seeking revenge four years later. The 1800 hand-off was America’s first transfer of power across party lines.

1824 and 1828

Two decades later, Adams’ son was engaged in a back-to-back presidential showdown of his own. It is hard to tell from the graph below, which shows the Electoral College count for each election, but John Quincy Adams won the first time around: even though he trailed Andrew Jackson in the electoral count, neither man won a majority in the four-way race, which threw the contest to the House. After the so-called “corrupt bargain,” the House chose Adams. Jackson, whom Trump has named as one of his presidential inspirations, beat Adams outright four years later as the Democratic Party’s first nominee.

1836 and 1840

After Jackson went on to serve two terms, his vice president Martin Van Buren attempted to succeed him. Van Buren triumphed over William Henry Harrison, the hero of Tippecanoe, in 1836, but the economy quickly turned south in the “Panic of 1837.” The downturn allowed Harrison to reverse his fortunes — although his luck would soon run out: he lasted only 31 days in office before dying of pneumonia.

1888 and 1892

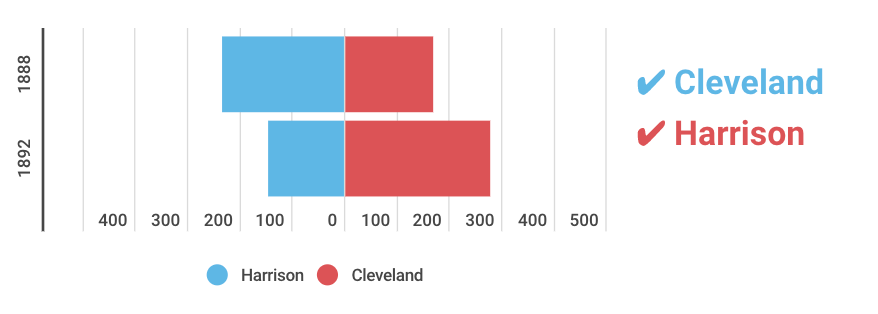

In an interesting bit of symmetry, the next presidential rematch would once again feature a presidential descendant: Benjamin Harrison, William Henry Harrison’s grandson. Harrison succeeded in knocking off the incumbent president, Grover Cleveland, in 1888. But Cleveland returned to the political stage in 1892, beating Harrison and returning to the White House — the only former president (so far) to pull off such a feat.

1896 and 1900

Around the turn of the century, William Jennings Bryan managed to win the Democratic presidential nomination an impressive three times. But the populist firebrand lost the White House each time; the first two defeats were at the hands of William McKinley. McKinley easily dispensed with Bryan both times; as you can see below, the incumbent president even expanded his winning margin the second time around.

1952 and 1956

Although White House rematches were relatively common throughout the 1800s, another half-century would pass before the next one — and almost 70 years have passed before the phenomenon has been repeated. Democrats were forced to scramble for a nominee after President Harry Truman decided not to run for re-election; they settled on Adlai Stevenson, but the “egghead” governor proved no match for the famous World War II general Dwight Eisenhower — in 1952 or in his second try four years later.

That last rematch, in 1956, contains some obvious parallels to 2024. The sitting president was, at the time, the oldest incumbent ever to seek re-election (at age 66, a spring chicken compared to Biden’s 80).

Although he faced questions about his age, Eisenhower was buoyed by his personal likability and his leadership during a pair of foreign invasions in Hungary and Egypt. Inflation played a key role in the campaign, as did a recent Supreme Court decision (Brown v. Board of Education). Although some rematch contestants coasted to their second nomination, Stevenson only won his party nod a second time after a spirited battle with a popular governor (Averell Harriman) and a southern senator (Estes Kefauver).

The sitting president, who had recently suffered a heart attack, traveled little in the campaign; he allowed television ads and surrogates (including his ambitious VP, Richard Nixon) to speak for him. Instead of focusing on policy, according to a 1960 study, Eisenhower’s campaign against Stevenson stressed his “personal qualities... his sincerity, his integrity and sense of duty, his virtue as a family man, his religious devotion, and his sheer likeableness.”

Not everything is a perfect parallel, of course. Eisenhower was much more popular than Biden and his first victory was much more comfortable (he won 442 electoral votes, the type of landslide we rarely see today in our evenly divided modern era). He again dispatched Stevenson with relative ease in 1956, unlike the fierce Trump-Biden struggle that will likely ensue in 2024.

(Another difference that should be noted: Stevenson accepted his defeats both times. In fact, after 1956, he gamely referred to himself as “the foremost authority on unsuccessful presidential campaigns.”)

In keeping with the thermostatic nature of American politics, most rematches have yielded a split decision, with one contestant winning the first go-around and their rival triumphing in the second. That could be considered a promising sign for Donald Trump — although Joe Biden can take solace in the fact that the two most recent rematches were won by the same candidate both times.

In all likelihood, neither factoid can tell us much, considering the degree to which presidential politics have changed over time. While the graphs above show several wild swings in the Electoral College between cycles, it would be considered a shock if more than a handful of states switch between Trump and Biden next year.

Even so, back in 1956, Stevenson supporters pointed to the history of presidential rematches to argue their candidate was favored. According to a New York Times article from September 1955, Democratic statisticians (speciously) declared that “history’s odds books” made Stevenson “a three-to-one favorite over President Eisenhower” because “the original loser toppled the incumbent president in three of the four previous instances” of White House rematches.

Republican operatives, according to the Times, had a ready-made response to these supposed statisticians: “Were any of those candidates named Eisenhower?”

This year, of course, it’s the Democrats seeking to stave off a different decision in the second campaign. But unlike the Republicans under Eisenhower, their best argument might be derived not from the strength of their standard-bearer, but from the weakness of their opponent. So as Democrats seek to buck rematch history this year, the more pertinent question might be: “Were any of those candidates named Trump?”

In other news

House Speaker Kevin McCarthy said his meeting yesterday with President Biden went “better than any other,” although it still did not yield any deal over the debt ceiling. In a letter to lawmakers, Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen stood by her estimate that the debt limit “X-date” will arrive in “early June, and potentially as early as June 1.”

Delaware Sen. Tom Carper announced his plans to retire next year after serving in the Senate since 2001 and holding elected office since 1977. He is the last Vietnam War veteran in the Senate. The seat is expected to remain in Democratic hands; Rep. Lisa Blunt Rochester, a close Biden ally, is the expected frontrunner. Her seat opening up could lead to state Sen. Sarah McBride becoming the first transgender member of Congress.

TikTok is suing Montana over the state’s ban of the popular video app. Lawyers for the Chinese-owned company argue in the suit that the Montana law, which is the first of its kind, “unlawfully abridges one of the core freedoms guaranteed by the First Amendment.” The law is set to take effect on January 1.

Special Counsel Jack Smith has obtained dozens of pages of notes taken by Donald Trump’s attorney, which show Trump asking whether he could flout a Justice Department subpoena for classified documents in his possession. The notes could play a critical role if Smith chooses to charge Trump with obstructing his investigation. Smith also reportedly subpoenaed records of the Trump Organization’s foreign business deals as part of the documents probe, but nothing substantive came of it.

More headlines

“E. Jean Carroll seeks new damages from Trump for comments on CNN” (NYT)

“More women sue Texas, asking court to put emergency block on state’s abortion law” (AP)

“Marianne Williamson loses top 2 campaign officials in a matter of days” (Politico)

“Oracle’s Larry Ellison gears up to spend millions to back Tim Scott's 2024 run” (CNBC)

Today in government

White House: President Biden and Vice President Harris will have lunch together.

Congress: The Senate is out. The House will begin consideration of a Senate-passed resolution repealing an EPA regulation imposing stricter emission standards for heavy-duty trucks.

Supreme Court: The justices have nothing on their schedule.

Thanks for reading.

I get up each morning to write Wake Up To Politics because I’m committed to offering an independent and reliable news source that helps you navigate our political system and understand what’s going on in government.

The newsletter is completely free and ad-free — but if you appreciate the work that goes into it, here’s how you can help:

Donate to support my work or set up a recurring donation (akin to a regular subscription to another news outlet).

Buy some WUTP merchandise to show off your support (and score a cool mug or hoodie in the process!)

Tell your family, friends, and colleagues to sign up at wakeuptopolitics.com. Every forward helps!

If you have any questions or feedback, feel free to email me: my inbox is always open.

Thanks so much for waking up to politics! Have a great day.

— Gabe