The week fluidity returned to Congress

A textbook Congress is a more fluid Congress is a more representative Congress is a more trusted Congress.

Good morning! It’s Monday, April 22, 2024. Election Day is 197 days away. If this newsletter was forwarded to you, subscribe here. If you want to contribute to support my work, donate here.

I’ve written a lot about government function and dysfunction in the past few months, making arguments that can be boiled down to three main points:

Last week, an exceptional flurry of legislative productivity proved all three points at once. Most notably, on Friday, sweeping bipartisan majorities in the House approved $60 billion in aid for Ukraine (311-112), which could have a transformative impact on the country’s war with Russia; $26 billion in military aid for Israel and humanitarian aid for Gaza (366-58); and $8 billion in aid for Taiwan and other Indo-Pacific allies (385-34).

These measures are all expected to receive bipartisan support in Senate, as is the “sidecar” bill that passed the House (360-58), which — among other provisions — would force a sale of TikTok, one of the nation’s most popular apps, which experts have long identified as a potential threat to national security.

In addition, the bipartisan Reforming Intelligence and Securing America Act was signed into law by President Biden, after passing the House (273-147) and Senate (60-34) a few days before. The measure reauthorizes the key Section 702 surveillance tool, while implementing 56 reforms that will expand oversight of the program and impose penalties for abusing it.

Each of these bills were unquestionably consequential and bipartisan, a combination not always seen on Capitol Hill, especially this year.

In the spirit of Passover, which begins tonight, it’s worth asking: what made these votes different than all other votes? What are the unusual conditions that make them so extraordinary in the context of the modern Congress? Here are two:

Lack of majority party agenda control: A congressional leader allowed a series of votes on bills that were supported by a majority of the chamber, even though many (or even most) members of the majority party were opposed.

Lack of party uniformity: Both parties allowed their members to vote their consciences, instead of imposing a unified position, allowing for ad hoc bipartisan coalitions to emerge and carry each bill over the finish line.

In other words, while the modern Congress is generally quite fixed — only a few pieces of legislation make it to the floor, and often the parties vote for or against them in blocs — these votes produced an unusual amount of congressional fluidity. Instead of pre-ordained, stage-managed votes along party lines, votes were held that divided the two parties, allowing for dynamic coalitions to enact substantive legislation.

The two conditions of fluidity I identified above would not have been extraordinary all that long ago. From the 1940s to the 1970s, the period scholars often refer to as “Textbook Congress,” they were quite common. In this era, Congress operated roughly by “regular order,” in which bills went through committees and were amended through more open processes on the floor. Party leaders acted more as “coordinators” than “commanders,” according to congressional scholar Phillip Wallach; the legislative process was instead driven by individual lawmakers, usually committee chairmen, who acted as policy entrepreneurs and cobbled together bipartisan coalitions to pass their priorities.

In the House, bills were often able to pass if they boasted support from a majority of the chamber, even if many majority party members objected. In fact, because the parties had not yet sorted along liberal/conservative lines, it was often more useful to consider a member’s geography than their party in predicting how they planned to vote. “No theoretical treatment of the United States Congress that posits parties as analytic units will go very far,” the political scientist David Mayhew wrote during this time.

To be clear, not all was perfect in “Textbook Congress.” Committee chairmen were able to use their considerable power to obstructive ends, especially on civil rights legislation. But, quantifiably, the Congress of this era got more done — and, it should be noted, the coalitions in power eventually grew more fluid themselves. As historian Joshua Zeitz has written, in the latter half of the “textbook” era, even as Democrats held congressional majorities, “shifting House coalitions that ranged from the center-left to the center-right were able to govern effectively,” as moderates found common cause on many issues across party lines. The thoroughly bipartisan Civil Rights Act of 1964 is, of course, the shining example.

The decline of congressional fluidity is best represented by this chart, created by a group of researchers in 2015:

In the chart, each dot is a member of Congress; blue dots are Democrats, red dots are Republicans. The dots are connected to each other if they voted together a certain number of times that Congress. As you can see, in the 1950s and ’60s, Congress functioned as one big, bipartisan blob. Then, slowly, the two parties begin to pull apart; by the 1990s, they vote as distinct partisan camps, with little to no crossover.

As Congress became less fluid, it also became less productive, as seen in the chart below, which covers roughly the same timeframe:

Does America want a more fluid Congress, of the kind we saw last week? Yes and no, I would argue.

“No” because Americans in both parties increasingly hate members of the other party, making them less likely to support their party members working across the aisle with the “enemy.” Structural factors make these feelings even more relevant in Congress: due to gerrymandering and geographic sorting, most members of Congress hail from safe seats, which puts an added emphasis on primary elections dominated by these highly partisan voters.

But “yes” because, even as emotional hatred towards the other party (“affective polarization”) has skyrocketed, “ideological polarization” — the distance between Democratic and Republican voters on the issues — has barely grown.

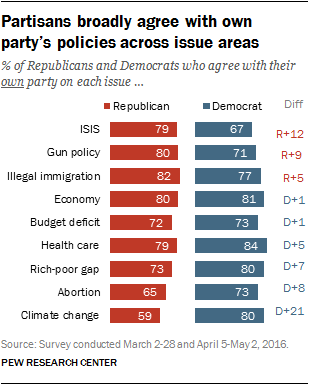

This is evident in the below graph from the Pew Research Center, which asked voters 10 political values questions and found that more voters give “consistently” liberal or conservative answers than in past surveys — but the vast majority of Americans (79%) still don’t. Unlike in Congress, where ideological polarization has increased to the point that members of the two parties almost always vote in two distinct blobs (see above), a plurality of Americans still hold a mix of liberal and conservative views.

This can be seen on issue after issue. Most Democrats and most Republicans agree with their party position on abortion — but, still, 15% of Democrats identify as “pro-life” and 20% of Republicans identify as “pro-choice,” fairly sizable factions of each party. In Congress, that would translate to about 40 pro-life Democratic members and 50 pro-life Republican members; instead, there is one pro-life House Democrat and only a handful of pro-choice Republicans.

On gun control, according to Monmouth, 20% of Democrats oppose an assault weapons ban, while 24% of Republicans support one. But when the House voted on an assault weapons ban in 2022, only 1% of Republicans voted for it and only 2% of Democrats voted against it.

The list goes on. No matter the issue, around 20-30% of a party’s voters disagree with their party’s position — which should, in theory, allow for bipartisan coalitions in Congress to pass broadly supported policies. But congressional leaders exert agenda control to ensure that votes are rarely held on issues that split their party; when such votes are held, the leaders expect uniformity, with their members voting along party lines even if they hold personally heterodox views on the issue.

In other words: Voters don’t think in party platforms, but members of Congress increasingly do. I believe this mismatch is an important one in American politics. It means that a less fluid Congress — which we usually have right now, last week excluded — is a less representative Congress. Combine that with the fact that the less fluid Congress is less productive as well, and it suddenly becomes easier to understand why trust in the legislative branch has fallen so much, creating a toxic — and potentially unsustainable — relationship between the government and its constituents.

Votes like last week’s, then, could offer a way out of our endless feedback loop of (unrepresentative) congressional polarization and mass civic disillusion.

Once Speaker Mike Johnson lowered the need for pure majority party agenda control, and both sides dropped their expectations of uniformity, lawmakers were able to vote their will on several major issues. The result were roll call votes that were still far from completely representative of the public at large, but which were much more representative than the typical vote, in which nearly 100% of both parties vote together in blocs despite considerable dissension within their public ranks.

On each vote, lawmakers reliably took a more hawkish view than the public at large — hardly a new phenomenon — but, for the most part, the heterogeneity within the parties is at least visible, unlike most congressional votes, when the parties enforce a level of homogeneity not seen within their electorates. On some, such as the Ukraine vote for the Republican side and the Section 702 vote for both parties, the outcomes came pretty close to nailing their public levels of support, a genuinely rare sight for a congressional roll call.

In another victory for fluidity, rank-and-file members received votes on amendments to several of these bills (a rarity in the modern Congress). This included amendments which were not backed by either party’s leadership, but which were given a fair vote, such as a key amendment to add a warrant requirement to the Section 702 reauthorization. That proposal failed in a rare tie vote, with almost perfectly mirroring coalitions of the two parties in support and opposition.

This new experiment with congressional fluidity isn’t necessarily built to last, as it has been fueled by the ungovernable House Republican majority more than anything else.

Still, as I’ve written previously, small changes could be made to make this fluidity more common, such as updating Congress’ rules to make it easier for bipartisan rank-and-file coalitions to assert floor control through discharge petitions. (In this case, even the threat of a discharge petition helped push Johnson to schedule votes on foreign aid.) There are also norms that could be adjusted to lessen the degree of congressional uniformity when major issues are voted on, so the parties act more like conferences and less like caucuses. One that I’ve previously pointed to is the norm that the minority party votes as a bloc against rule resolutions, even on underlying bills they support; Democrats dispensed with that norm here, just as Johnson dispensed with the norm of only scheduling votes with near-unanimous support of the majority party.

In his book “Why Congress,” Phillip Wallach argues that policy changes that go through open, bipartisan processes in Congress (even complicated ones) are viewed as more legitimate by the public than changes implemented by the judiciary and the executive. (He points to the difference in public responses to Brown v. Board of Education and the Civil Rights Act of 1964 as evidence).

From there, it follows that public distrust of government institutions will skyrocket when Congress takes a backseat on major issues, as it largely does today. I’d argue that the distrust is compounded (and such productivity is made more difficult) when, on the bills that do make it the floor, lawmakers routinely vote along party lines, in a way that is unrepresentative of their heterodox-thinking public.

If that’s true, then congressional fluidity isn’t just a recipe for more government function. It’s a necessity for improving our country’s civic health.

Thanks for reading.

I get up each morning to write Wake Up To Politics because I’m committed to offering an independent and reliable news source that helps you navigate our political system and understand what’s going on in government.

The newsletter is completely free and ad-free — but if you appreciate the work that goes into it, here’s how you can help:

Donate to support my work or set up a recurring donation (akin to a regular subscription to another news outlet).

Buy some WUTP merchandise to show off your support (and score a cool mug or hoodie in the process!)

Tell your family, friends, and colleagues to sign up at wakeuptopolitics.com. Every forward helps!

If you have any questions or feedback, feel free to email me: my inbox is always open.

Thanks so much for waking up to politics! Have a great day.

— Gabe